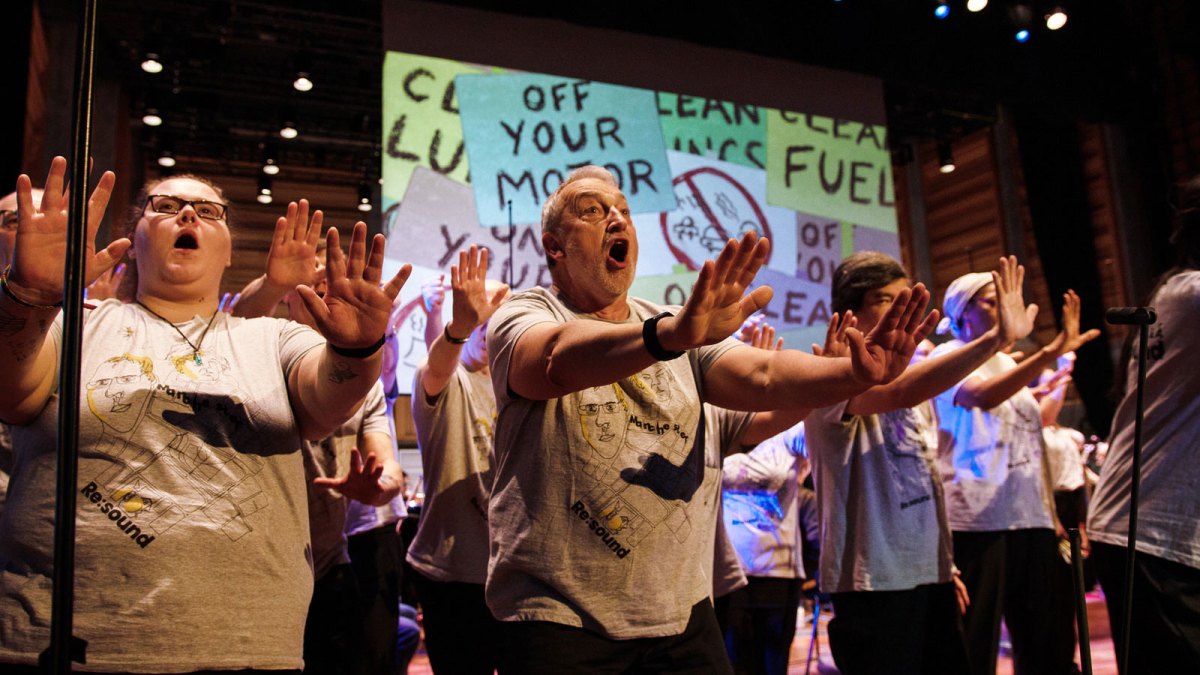

“We want to see your faces!” It’s not an unusual thing to hear in a choir rehearsal. Getting your head out of the score to look at conductor and public works musical wonders. But it had a sharper quality when I heard Rob Gildon say it in a workshop run by Streetwise Opera at the Southbank Centre in London. Streetwise, a music charity that works with people who have experienced homelessness, was preparing several performances in November. Right then, the group of 20 or so participants was practicing the Neapolitan street song “O sole mio,” the “Ombra mai fu” that opens Handel’s “Serse,” and, dividing in two, the concluding duet from Monteverdi’s “The Coronation of Poppea.”

I felt a brief flush of shame when Gildon spoke. I have walked past people who are living on the streets of London, averting my eyes to avoid a difficult encounter, or shutting down a conversation when approached by someone asking for help. The act of looking away denies the humanity of people experiencing homelessness and is part of what makes it so lonely. In this respect, Gildon’s words crystallized the value of what Streetwise Opera does. Performing means establishing an intimate emotional link with relative strangers—an audience—which is created in part through the exchange of looks. A musical performance is empowering and dignifying because of the recognition it demands and the connection it invites.

A sadly common impulse is to look away, but it is increasingly impossible to do so. Over a decade of political failure and austerity has seen homelessness in the UK soar by over 73 percent since 2010. It will undoubtedly worsen with a spiraling cost of living and exorbitant rents. If, after a performance, you have stood outside one of the pubs near the Royal Opera House, London Coliseum, or Southbank Centre, the crisis is plain to see. Streetwise Opera’s work tries to align these apparently separate spheres. UK Home Secretary Suella Braverman’s remark last week that those living on the street in tents do so as a “lifestyle choice” gives an indication of the kind of cultural and political environment in which Streetwise works.

Upstairs, there are preparations ongoing for a red-carpet event; downstairs, Streetwise Opera rehearses and pauses for pizza. Dee has been singing with Streetwise Opera since 2017. She is in her 70s and speaks with a lively Australian twang. In rehearsal, Dee is among the most confident and experienced members of the choir, singing without much recourse to the music or text. “People come to Streetwise and they leave their problems at the door,” she tells me. “You meet friends, you continue to sing…and once you’re singing, they work you so hard you don’t have time to think about those problems. And when you walk out, you’re too tired to think about them.” She leans forwards conspiratorially: “They give us earworms.”

In November, Streetwise Opera will give two performances of Gavin Bryars’s 1971 work “Jesus’ Blood Never Failed Me Yet” in London, joined by the composer’s own ensemble and The Choir With No Name, another music charity for those who have experienced homelessness. It is one of their many far-ranging projects. In 2019, Streetwise performed scenes from “Carmen” at the Royal Opera House. In 2021, they created the nine-minute music and video installation “Unseen” with composer John Barber, dramaturg Elayce Ismail, and soprano Abigail Kelly, using Zoom and in-person workshop in hostels.

At another session, I watched their participants working with Pete Letanka, creating material for a new project called “Re:Discover” and workshopping three characters: a girl late for school, a fare-dodger, and an anxious security guard. The way this work shines a spotlight on such ordinary characters—a million miles away from the court of Mantua—is echoed in the project’s musical bent, which draws in works by marginalized composers including Ignatius Sancho, George Bridgetower, Joseph Bologne, Florence Price, Margaret Bonds and Shirley Thompson. With their partner groups in Nottingham and Manchester, Streetwise will create three new operas to debut in summer 2024, with text by actor and author Paterson Joseph. Joel Thompson, composer of “Seven Last Words of the Unarmed,” joined in the session and took questions—Streetwise participants had seen chamber choir Tenebrae sing his music in rehearsal at Wigmore Hall the day before. The unacknowledged or vulnerable in society are thematic waypoints in much of Streetwise’s work, though this isn’t to underplay the joyfulness and relaxed jocularity of the rehearsals, an atmosphere familiar to anyone who has made music with others.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

Bryars turned 80 in January. “Jesus’ Blood Never Failed Me Yet” has been performed 19 times this year. Among these are two that Streetwise Opera will present on November 9 at the church of St Martin-in-the-Fields, just off Trafalgar Square, the base for an eponymous, UK-wide homelessness charity. Streetwise Opera has had a relationship with the piece since 2017, when the Reverend Richard Carter, a priest at St Martin’s, approached Bryars about performing the work in their annual service remembering those who have died homeless.

The 1971 composition is simple enough in design. It begins with a 26-second recording, made by Bryars when creating music for a documentary about the Elephant and Castle neighborhood of London, of a homeless man singing a simple, open-hearted lyric: “Jesus’ blood never failed me yet / That’s one thing I know / for he loves me so.” The looped phrases are given a simple harmonic underlay. As Bryars’s penumbral orchestration seeps in—clarinet, viola, cello, double bass, the bottom end of the piano—the music thickens and expands, its emotional crevices cracking open.

There is no known source for the tune or words, nor an identity for the homeless man singing it, yet it is still hauntingly, uncannily familiar. In its quiet insistence, it is both deeply private and somehow open enough to allow listeners from all kinds of backgrounds and traditions to charge it with their own emotional meaning.

Bryars tells me that the textural and harmonic underlay provided is just a frame for the singing voice on the recording, whose contours have a crystalline fragility but also speak of musical assurance in the phrasing and intonation. Bryars recalls the meticulously faithful folk song transcriptions of Percy Grainger, which tried to retain the irrational melodic inflections and rhythmical kinks not easily amenable to notated musical traditions. “Everything I do is to respect that voice, and to move with it,” Bryars says. The central fragment is not chopped as mere musical fodder—compare it to Steve Reich‘s treatment of the San Francisco preacher he recorded for the apocalyptic hypnosis of “It’s Gonna Rain”—but bathed in tender harmonic and timbral light. It’s like staring into an unchanging face for 30 minutes: the musical equivalent, perhaps, of Marina Abramović’s “The Artist is Present.”

Bryars is keeping his calendar clear for the annual service at St-Martin-in-the-Fields commemorating people who have died homeless, which takes place this year on November 9, until 2042—at which point he will be 99. “If something came up on that date, I would not accept it,” he says. “It’s sacrosanct.” It is easy to understand why: “Jesus’ Blood” complements the most heightened moment of the service. As it plays, the names of around 150 people are read out; all the while, the congregation approaches the altar to receive a card bearing the name of someone who has died.

While this unfolds, singers from Streetwise Opera and their partner organization The Choir with No Name join in singing—sometimes melody, sometimes harmony—before the congregation does so in turn. Carter described the effect of Bryars’s music in this service in his 2019 book The City is My Monastery: “It is a sound that moves beyond words, beyond the tune itself…it is as if the song actually becomes that redemption, that healing, that love.”

For Streetwise Opera participants, this is an experience of incredible intensity and vulnerability. Some of them will have known, personally, those whose names are read out and written on the cards. “I can’t actually look at the card during the service, while I’m accompanying the choir—I wouldn’t be able to keep it together and play,” Aga Serugo-Lugo, a Streetwise workshop leader, confides during a break in rehearsal. (He nonetheless reassures me he looks at it after the music is done). Bryars tells me he keeps every card he has been given.

The atmosphere of emotional rawness and openness described feels like an ideal match for Streetwise Opera. “The first time I went,” Bryars recalls, “they were working on a scene from ‘Carmen’… I was just astonished by their commitment. What they were doing was not easy even with amateurs who were not homeless, or experiencing other kinds of difficulties.”

Bryars describes the group’s careful inclusivity. “There was one guy who had a fantastic voice, but was always singing the wrong stuff (though it was very beautiful),” he chuckles, “but they had the most gentle way of bringing him into it, embracing him.” He adds, “They give a sense of ownership and responsibility to everyone involved.” Carter finds their performances equally powerful. “They are a community choir who sing without anxiety…with raw energy and joy—the joy of being together.” He continues, “I don’t know a choir who gets a bigger reception, and wins the audience over without pretense or affectation.” He believes that, for Streetwise Opera, singing “is a form of solidarity, a way to overcome the struggle.”

Perhaps the most powerful testament of this was Streetwise Opera’s participation in a 12-hour overnight performance of “Jesus’ Blood” at Tate Modern in 2019. People often talk about the arts feeding the human spirit, and providing warmth or comfort. We know singing can help with all kinds of ailments. But in this instance, music-making provided more than metaphysical succor.

Dee described the performance to me: “We were spoiled. We got meals, we got breakfast, we got music. The nice part was that everybody was able to come in. The homeless, people who sleep on the street—they could come in and sleep on the floor, they could help themselves to coffee, to meals…They had the same experience as everyone else in the audience.” How did she feel when it was over? “It was invigorating and relaxing at the same time…I’ve never forgotten it. I’ve forgotten many of our performances, but I’ve never forgotten Gavin Bryars.” She adds, “We wanted to sing all night. Singing the harmony was like having sugar in your tea. It was just a sweet feeling…like you’d reached the end of the world, a pinnacle.”

Hugh Morris, in a recent article on the Pan-Caucasian Youth Orchestra for VAN, described the precious normality that the course allowed its young musicians to experience. Streetwise Opera also uses music to welcome and nourish people. On November 9, they will also perform Bryars’s “The Open Road,” which they commissioned in 2012. It is a setting of Walt Whitman in which Bryars’s umber ensemble writing is offset by the bright flecks of electric guitar, whose countermelody lights the musical way. Whitman’s all-embracing poetry says: “Here the profound lesson of reception, nor preference nor denial.” Bryars’s setting culminates with the three voice parts joining together. “Will you give me yourself? Will you come travel with me?” they sing. “Shall we stick by each other as long as we live?” ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.