I. (beauty)

“I really think that beauty can come from ugliness,” Marina Abramović told me as she gestured to several pictures of her boobs. We were seated across from each other at a long wooden table in her Greenwich Village apartment, casually sparring about the place of silence, violence, and beauty in art. The performance artist bustled around the airy, well-lit space, her long dark hair swinging behind her. She yanked a few books from the shelves and showed me pictures from her 1975 performance art piece “Art must be Beautiful, Artist must be Beautiful.” In the performance, a topless Abramović frantically brushes her hair while repeating the title of the piece over and over. This repetition evolves from a self-admonishment to a numbing chant to a frightening meditation on the expectations, whether conscious or unconscious, that spectators and audiences bring to their artistic experiences.

Abramović went on, “I truly believe that art is not about beauty. Because I don’t believe that people should choose to buy a painting because of the color of the sofa or the carpet in the living room, you know? They miss the point of art. So I made this very simple piece with a metal comb and a metal brush which I have in my hands, and I’m brushing and combing my hair very wildly, while always repeating this same question: ‘art must be beautiful, artist must be beautiful.’ But, you know, in an ironic way. Because I really believe that beauty can come from ugliness and disorder and asymmetrical experiences. If we are fixed on the classical idea of beauty, we are missing the point.”

The piece is a deft and brutal commentary on the arbitrary “beauty standards” demanded not only of women’s bodies but of art itself. I told Abramović how troubled I had been when my undergrad music majors wrote in-class essays about how it was basically OK that Wagner was anti-Semitic, since his operas were “objectively beautiful.” With “Art must be Beautiful, Artist must be Beautiful,” Abramović echoed questions raised by Yoko Ono in her 1965 “Cut Piece,” about the vulnerability of the female body within contexts of performance and spectatorship, misogyny in the art world, and the hegemonic forces that shape our concepts of “beauty” and “art” in the first place. Abramović told me that she is less concerned with the material than with the immaterial, adding that art should “move you emotionally” and “hit you in the stomach” rather than embody a prescribed format or style.

Throughout our conversation, Abramović’s musings were peppered with contradictions. She said she “actually doesn’t like violence,” but nostalgically recalled her 1973 piece “Rhythm 10,” for two tape recorders and 20 knives, in which she literally stabbed herself while playing the Russian “five finger fillet” game. She thinks that “beauty can come from disorder,” but recently has begun mandating that audience-goers forfeit their phones and cleanse their ears with a prescribed period of silence before listening to music. She claims that we shouldn’t fixate on “classical ideas of beauty,” yet she advocates for methods of listening that reify certain musical sounds as being more worthy of focus than other sounds. I struggled to keep up with the 71-year-old performance artist as she flipped through books and images of her past performances, pulled up videos on her laptop, turned my own questions back on me, and flurried from thought to thought.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

II. (presence)

Abramović has tested the limits and boundaries of art and beauty since the early 1970s, when she first began putting on performance art pieces that tested the limits of both artist and audience. Her early works were dangerous, bloody, visceral. Perhaps most well-known is her more recent work “The Artist is Present.” The piece was staged in 2010 at New York City’s Museum of Modern Art, which was hosting a retrospective of Abramović’s works. Abramović performed the confrontational, though totally silent, piece for a total of 736.5 hours. In an ironic contrast with her earlier works—so fast-paced that the photos she showed me were blurred—Abramović sat totally still at a table in the museum’s atrium. Museum visitors were given the opportunity to sit across from her and get stared at, an experience so universally intense that it inspired the Tumblr “Marina Abramović Made Me Cry.”

Much of her more recent interest in music specifically stems from her focus on sound and silence, and the possibility of silent meditation to “prepare” a listener for musical sound. Abramović claims that she has “no ear for music”—a bourgeois idea of musical “giftedness” that adds yet another strand to Abramović’s thicket of contradictions—but that hasn’t deterred her from developing the “Abramović method” for listening, which she described as “an exploration of being present in both time and space, which incorporates exercises that focus on breath, motion, stillness, and concentration.” Within this method, there is an emphasis on bodily awareness and absorption of the music, but also what seems to me a very unidirectional attention to sound as an object rather than a process. The insistence upon “presence” implies that there is definitely a right (and a wrong) way to listen, which itself relies on ableist notions of “correctness” and “normalcy.” I have to admit to being skeptical, although I have not experienced this listening method for my own yet.

The Abramović method centers on its author’s obsession with artistic and audience presence. Although much of her early performance art emphasized the isolating and alienating role that the artist must play, Abramović is now more interested in the possibilities afforded by collectivity and community. I asked Abramović what her ideal musical program would be, if money, logistics, and “political correctness” were of no issue. Abramović said that it would be a “communal event” where “music is the only source of the experience.” Like “a Sufi ritual, or Woodstock,” the musical festival would highlight experiences of collectivity and presence rather than a specific genre or type of music. The listeners would eat simple food so as not to be distracted from the music, which should really be the sole source of sensation. “Oh, and the audience would all be blindfolded.”

III. (violence)

What about the capacity of sound (and even music) to transmit not beauty but violence? I tried to push Abramović on this question. Even though the human voice is not inherently violent, it can become violent within certain contexts. Musicologists like Suzanne Cusick have explored the use of music as torture, such as at Guantánamo, where detainees were subjected to music at high volumes for long periods of time. Music in these instances became a vibratory force capable of causing physical and psychological pain. Given Abramović’s penchant for visceral performance experiences, occasionally involving her own blood, pain, or loss of consciousness, I was eager to hear her thoughts on the use of sound itself as violence.

Abramović responded, “Sound can be very violent…” Her tone became soft as she reflected on the harmful possibilities of the human voice. “When I was a child, my father and mother would be very violent to each other, and every time they would raise their voices I would just freeze.” She seemed to be acknowledging that sound is not inherently superior to any other medium. She showed me more pictures, this time from “Rhythm 10.” Each time she cut herself she would pick up a new knife until she had made her way through 20 knives; she then played back an audio recording of the first round and tried to duplicate the movements and “mistakes” based on sound alone. When I asked her what sort of sounds she made during “Rhythm 10,” she gasped as a demonstration.

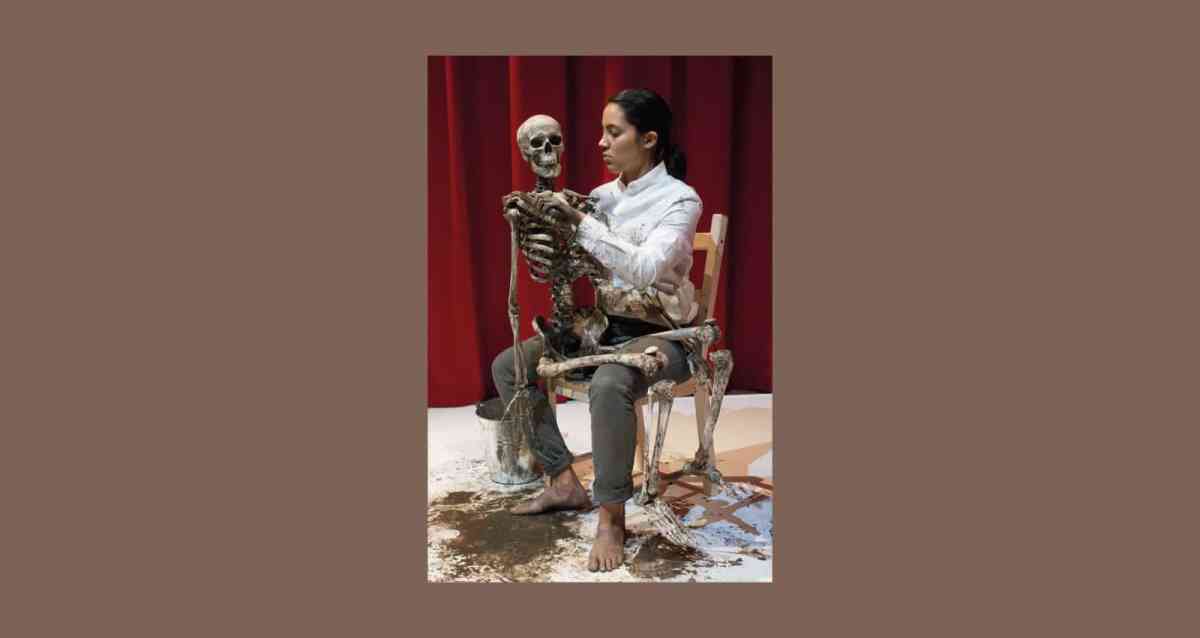

Abramović’s newest musical project will examine the violence to which female opera characters are subjected. “I’m doing an opera, which I’m directing and playing in,” she said. “It’s called ‘Seven Deaths,’ and it’s going to premiere in 2020 at the [Bavarian State Opera]. In this opera, I only play deaths—women dying. That’s it. Because in every opera a woman dies. Strangulation, burning, karikiri, jumping [suicide], suffocation, tuberculosis…” The opera will be an ironic take on the misogyny perpetuated by centuries of opera plots.

IV. (silence)

I found myself wondering what this opera would sound like. I asked Abramović why, at the Park Avenue Armory premiere of the Abramović method, the audience relinquished their cell phones and sat silently wearing noise-cancelling headphones for a half an hour in order to be fully prepared for 75 minutes of J.S. Bach. Abramović explained that pianist Igor Levit had chosen the “Goldberg Variations” for the Park Avenue Armory series of performance, but that this method of listening can work with anything. The Abramović method will come to the Alte Oper in Frankfurt in March 2019, where the performance will be six hours long and include a variety of musics. Yet the focus still remains on…focusing.

“This is a disaster!” Abramović said, in reference to contemporary society’s incapacity to focus or to listen. (Apparently millennials have not only ruined homeownership and the napkin industry, but also listening as a skill.) She explained to me that “the Abramović method was not necessary 20 years ago… we have lost our ability not only to concentrate but to listen.” She went on, “When we go to listen to anything, we take our phones, you know, in case we get messages or we get bored. We’re constantly doing something with our phones and not concentrating on what is actually happening. So we started taking people’s phones away. People always have a device in between, they aren’t engaged with the performance in front of them, they have no direct experiences anymore.”

Besides Abramović’s ideas about sound and listening, she also has an idiosyncratic taste in music. “I find that most pop music is incredibly violent,” she said. “From punk, there was this explosion of violence…the music I really like is ragas, which is a totally different thing, it makes low tones, and overtones, and it’s not this beat [hammering on table with fist]. I can’t stand the beat, it gets on my nerves.” At this point in the interview, I became terrified that Abramović would realize who I was: a millennial who subsists on shitty pop music and avocado toast; who wouldn’t remember what it was like to concentrate 20 years ago, because I was in second grade.

Upon the close of our interview, I got up my courage to inform Abramović that we have the same birthday. She did some mental math and, aghast, informed me that she could be my mother before kissing my forehead and bidding me farewell. I wandered back outside and immediately got out my phone, scrolling through notifications and then opening Spotify so I could listen to some pop music. With Sia hammering in my ears, I found myself wondering if there could be art, or beauty, in a lack of concentration—in background music, in the agency to listen the way one wants. If art can arise from ugliness, surely it can also come from an accident, a pounding beat, a lack of focus. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.