On the evening of March 7, 1983, the French-Canadian composer Claude Vivier went for a drink at a bar in the Belleville neighborhood of Paris. He picked up a young man there and brought him back to his apartment for sex. The man then stabbed Vivier to death. If, before he fled, the killer had stopped to look at the composition Vivier was working on, “Glaubst Du an die Unsterblichkeit der Seele” (“Do You Believe in the Immortality of the Soul”), he would have read the following words:

I couldn’t tear my eyes off the young man it seemed as if he had been sitting across from me for all eternity and it was then that he addressed me, he said “Quite boring this metro, huh!” I didn’t know how to respond and said, somewhat disoriented at having my gaze returned “yes, quite” then perfectly naturally the young man came to sit down next to me and said: “my name is Harry” I answered him that my name was Claude then without further introductions he took out a knife from his dark black vest that he probably bought in Paris and stabbed me right in the heart.

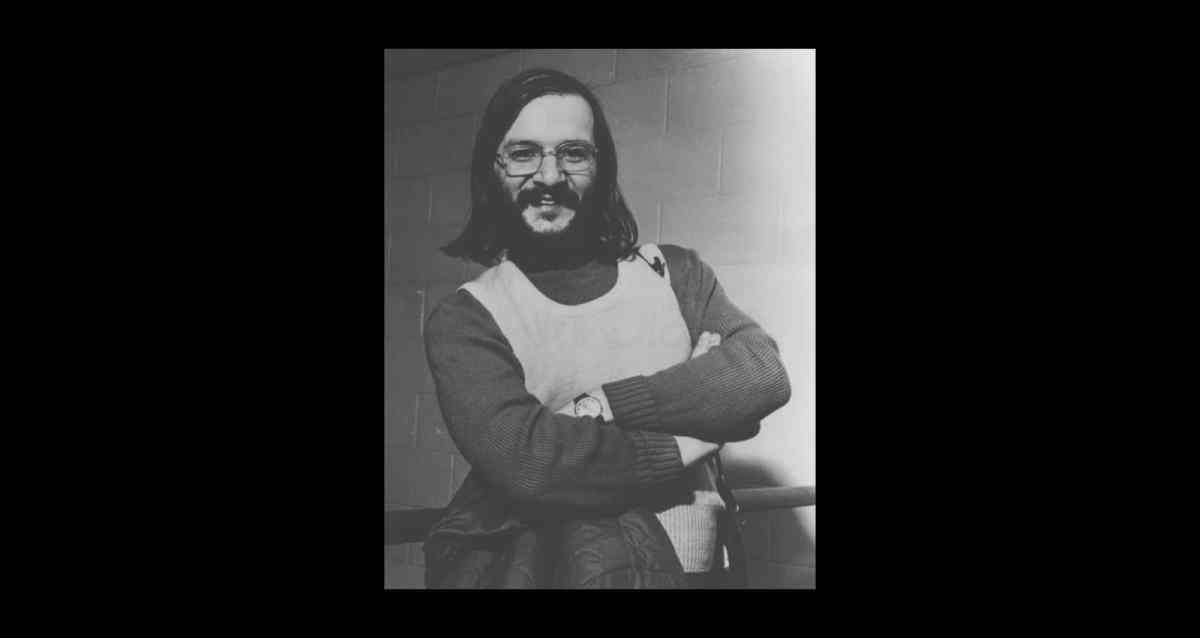

Vivier was 34 years old. Four days later, the police forced entry and found his body. Had he predicted the circumstances of his own murder?

The composition “Glaubst Du an die Unsterblichkeit der Seele” is scored for three synthesizers, percussion, and 12 voices, and contains all the typical elements of Vivier’s style: theatrical speech; invented languages; intuitive, Spectral-sounding harmonies; and, uniquely among the avant-garde composers of his circle, luxurious melodies. These elements are used with a freedom that shows Vivier’s increasing belief in his own abilities.

The work starts with a static, ritualistic passage, and moves to an almost Romantic melody over freely repeating tones in the voices, like several simultaneous religious chants. Singing while covering and uncovering the mouth, a color present in many Vivier pieces, and the Indian call of childhood cowboy games, becomes part of an alien ceremony, both primitive and futuristic. About three minutes from the end, the climactic passage is reached. The music becomes static, this time far more intensely so. The story of the man in the subway is spoken beneath a soprano melody of irregular durations.

This story is not the only one in the work whose text has the character of a premonition. Words come out from the texture: “Ewige Liebe” (“Eternal love”), “My love, my love.” In the beginning, marked by Thai gongs, synthesizers, and vocoder, the first tenor recites:

“You have that I’ve always wanted to die for love but…how strange it is, this music…which doesn’t move…I’ve never known…known how to love…yes”

The beginning, with the line “I’ve always wanted to die for love,” seems to refer to Vivier’s past. The story with which the work ends refers to his future.

Vivier was born on April 14, 1948, to a mother about whom almost nothing is known. He spent two years in an orphanage before he was adopted by the Viviers, a strictly Catholic, working-class Quebecois family. While the mysterious circumstances of his birth pained him, they also led him to develop a sense of mysticism around his origins, which in turned nurtured his artist mission.

As a teenage, he entered a Catholic seminary. There he discovered music and, slightly later, realized he was gay. (An earnest essay on Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 he wrote there reminds me of an essay I wrote on the same piece at the same age.) In a school exercise that may have given Vivier’s sexuality away early, the boys in the seminary trade descriptions of one another—Vivier praises the boy’s physical features and understanding of beauty, while they write more banal, friendly things. Vivier outed himself at age 18 and was kicked out of the seminary, though that did little to interfere with his enjoyment of gay life.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

Vivier began studying composition in Montreal and eventually made it into Karlheinz Stockhausen’s class, whom he worshipped; the German master may have appreciated the admiration more than Vivier’s actual talent, but he was a major influence. A trip to the Far East, where Vivier visited Japan, Thailand, Iran, Java, and Bali, strengthened his interest in exotic percussion timbres, abstract music theater, and ritualistic performance.

Vivier was, by most accounts, happily and vivaciously sexual—he had a long-term apartment within walking distance of a popular Montreal cruising spot. One friend recalls being told of his orgies in local bathhouses. His preferences ran towards the “leather-clad, muscular, biker type.” He seems to have had an interest in BDSM, telling his friend, the experimental artist Robert Racine, that “Violence is fascinating. Erotic also.”

Vivier received a scholarship to live in Paris in 1982, where he planned to write an opera based on new research into the death and sexuality of Tchaikovsky. In January 1983, he began work on “Glaubst Du an die Unsterblichkeit der Seele,” as a standalone work. Around the same time, he began a short but passionate affair with an American expatriate named Christopher Coe, who later wrote a memoir, in which he recounts a fictionalized version of Vivier. The affair ended because Vivier found out that Coe had a boyfriend in New York. It was one of Vivier’s few serious relationships.

Their brief affair was over by January 24, according to a letter to a female friend. On the evening of January 25, Vivier picked up a man at a bar for sex who “grew violent” and attacked him with a pair of scissors and made off with the contents of his wallet. (Vivier suffered superficial neck wounds.) He was shaken, and reached out to friends, though his closest confidantes were not in Paris, but at home in Montreal or among his old college buddies in Germany. While there, he told friends he had sworn off gay bars, before going into one a short while later. When confronted, he said he meant only to avoid them when in Paris.

CLAUDE VIVIER: “LONELY CHILD” (1980), MARIE-DANIELLE PARENT (SOPRANO), ORCHÉSTRE MÉTROPOLITAIN DE MONTRÉAL, SERGE GARANT (CONDUCTOR).

The photographer Robert Mapplethorpe famously said that “S&M means sex and magic, not sadomasochism.” Vivier and Mapplethorpe had much in common—both men were raised Catholic, liked men in leather, continued to have sex with women after coming out, and immersed themselves in ritual and mysticism. It is easy to imagine that Vivier approached his sexual encounters with a desire, similar to Mapplethorpe’s, to experience magic, to transcend.

Both men intuitively associated danger with eroticism. While their friends warned them to be careful, they sought out sexual encounters outside their respective artistic cliques. This was also a function of the times: before universal knowledge of AIDS, anonymous sex was simply an essential part of gay sex. Vivier never lived to see a world in which monogamous gay relationships were common.

In this world, gay men were a far easier target than they are today—though Vivier was out and impossible to blackmail, opportunists still viewed the gay bar as a good place to make a quick buck. The common feature of the attacks on Vivier was money, even though he didn’t have very much of it. Coe expressed his surprise at Vivier’s lack of inheritance, which may also have played a role in their breakup. Because of this, Vivier’s friend Philippe Poloni called the American “cruel.”

So while Vivier clearly hadn’t given up on his active sex life, one gets the sense that he was beginning to look for something more settled. (Of course, the two aren’t mutually exclusive. An open relationship model might have worked wonders for him.) His brief relationship with Coe was his best shot at stability so far, and the betrayal hurt. Mapplethorpe also said that S&M, for him, “was all about trust.” What if trust was what Vivier was looking for?

In late October 1983, Vivier’s murder was caught, and immediately confessed to his crimes. He was a 20-year-old drifter named Pascal Dolzan; he additionally admitted murdering two other gay men in similar situations. His motive was also money, and he showed little remorse. “ ‘For Dolzan,’ the police explained, ‘his crime was simply a sadomasochistic ritual that ended up badly.’ ” He was sentenced to life in prison.

Vivier’s biographer, the late musicologist and performer Bob Gilmore, spoke with his friends, who were split into two camps. Some believed that Vivier’s darker angels got the better of him, and that he willingly took unreasonable risks, perhaps looking for a way out of the spiral. The other camp, citing his excitement about various upcoming premieres and his general will to live, maintain that the murder was a result of his naïveté, the connection to the text of “Glaubst Du an die Unsterblichkeit der Seele” a eerie but ultimately irrelevant coincidence. Gilmore, soberly, concurs with the latter group. On the strength of the proof, I think he’s right.

But there is one detail I can’t get quite past. Why did Vivier write that his assailant pulls his knife out “from his dark black vest that he probably bought in Paris”? To me, this doesn’t sound like a tragic premonition—it sounds like gentle mockery of the transparently wannabe-bohemian fashion sense of an expatriate lover.

Vivier had finished the first six minutes of “Glaubst Du an die Unsterblichkeit der Seele” before he met Coe, but the final section—which includes the text about the young man who stabs him—was written during their relationship. After the breakup, Vivier wrote of a “blind fear of composing.” We don’t know exactly when he wrote the premonitory text, but I like to think that the detail of the vest was added as a memory of Coe.

Seen this way, the final recitative of “Glaubst Du an die Unsterblichkeit der Seele” becomes something more comprehensible than an early premonition of death. It is a Romantic metaphor for love betrayed. That this metaphor became prophecy says much about Vivier’s state of mind and risky behavior at the time of his death, but there’s no denying the essentially mystical quality of the coincidence. “Sex and magic”—in that phrase, there’s room for black magic too. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.