I first met Betsy Jolas, a distinguished composer with a nearly 70-year career, in 2005. I had received a scholarship to attend the Academie Villecroze in Provence, France, and performed a piece of hers there. The work was “Mon Ami,” for a pianist; it’s unique in that the pianist sings, her voice melding with the sound of the piano.

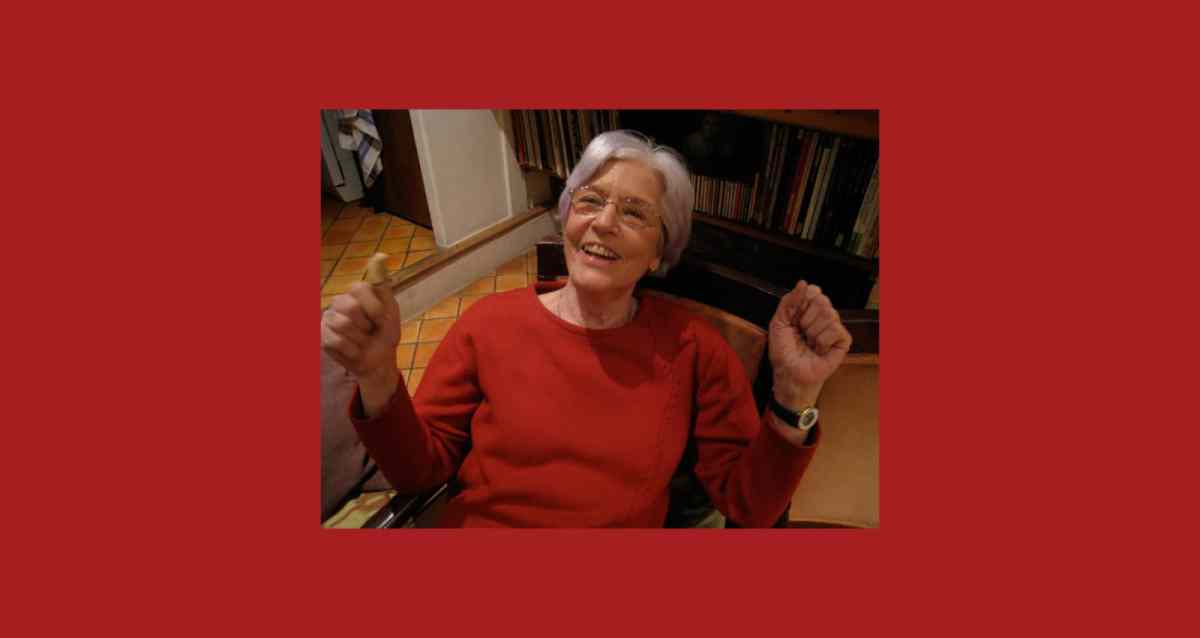

In October, I contacted Jolas to ask her for an interview. I wasn’t sure if she would remember me, but Jolas—who will turn 90 in August—remarked that she recalled my playing of “Mon Ami” and would be happy to talk. I reached her at home in Paris to ask her about what’s changed in contemporary music since she started, how her music frustrates PhD students, and why she’s still not resting on her laurels.

VAN: What composition projects are you working on right now?

Betsy Jolas: Recently, I’ve been writing a Double Concerto for piano and trumpet for Roger Muraro and Håkan Hardenberger. I also have the premiere of my opera “Iliade l’amour” coming up in March, and in June the Berlin Philharmonic will premiere a piece of mine called “A Little Summer Suite,” which they commissioned.

A Double Concerto for piano and trumpet is a unusual instrumentation. Where did the idea for the piece come from?

Håkan Hardenberger, the trumpet player, and Roger Muraro were performing somewhere on the same program, but not in the same piece. Musicians like to go out for drinks after concerts, and apparently they started talking and throwing ideas back and forth. They wanted to play together and started looking for a composer to write a piece for them. Since I had already written a solo piece for Roger, and Håkan was a classmate of my son’s, they thought of me.

I had just finished the piece and was preparing for another premiere at the Tanglewood Music Festival when I found out that Håkan had a concert on the same day. So after his concert, I went over to him and handed him his part.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

You are active musically in the U.S. as well as in Europe. Are there major differences between the American and European musical cultures?

Oh yes. The music training is very different. For example, in France there is a system that we call écriture: students spend a lot of time learning counterpoint, harmony, and 20th century writing. In the U.S. they focus more on analysis—they don’t develop their ears. Students use the piano when they compose, or even the play function of their music software!

Speaking of which: it often seems like contemporary composers are relying increasingly on music technology in their work. What do you think of this development? Do you think that technological tools are effective aids for composers, or are they bad for their craftsmanship?

It depends on how they are used. A composer has to choose his techniques—I personally prefer acoustic instruments. Electronic tools became available too late in my long life. I don’t think I have time to get involved now, though I might if I was younger.

You have developed a very distinct style of your own. How did you get there? What was your source of inspiration?

I was never preoccupied with style per se, I only tried to put down clearly what I heard in my head. A while ago, some PhD students were trying to find twelve-tone rows in my music, and they got frustrated when they couldn’t find any. I told them to stop trying! I don’t have a system—I can’t teach how to write music that sounds like mine. I recommend reading books, going to museums and all kinds of different concerts. That’s what every artist should do.

Have you noticed that many musicians don’t like music nowadays? They only go to the concerts that they’re playing in, or where their own music is being performed. I want to remain curious. You should never think that you’ve achieved something. Even at this point of my career, I always feel a bit worried.

I think that many composers, especially younger ones, feel like they need to create something completely new.

It’s just a question of culture. My roots are in the entire history of music, not just in contemporary music. I feel privileged to be related to all that great music of the past.

I’ve noticed that in every composition course there is at least one wannabe Lachenmann. What do you think about imitating other composers?

Imitation is OK. There is a time for it. I still imitate and quote quite often, but nobody notices it [laughs]. As Pierre Boulez said, composers are great predators—he was one, too. But if you try to be someone else you might as well just give up.

You are a composer who also happens to be a woman. Has your gender ever had an impact on your career?

Certainly. When I started I had no role models and a lot of doubt about being able to compose. There were not that many women studying composition at the time. Also, I didn’t like to go to the concerts of female composers because I simply didn’t like their music. Finally, in the late 1960s, one of my works was first performed in a concert featuring music of Boulez and Schoenberg; that was the first time I felt confident about myself as a composer. It’s only quite recently that women are able to find the time and space to create music. Have you read Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own? I’ve been looking for that room all my life. I have it now. Although I always knew that I wanted a “normal” life—including a family—music still makes me truly happy.

Are composers treated differently according to their gender?

Yes. For example, the age of female composers is almost never disclosed. The birth years of male composers are very often included in concert programs, but they almost never do the same for women. But, as I’ve pointed out time and again, I’m not an actress or a singer. My age is not a secret: everybody knows how old I am.

People love to debate whether women and men compose differently. What do you think?

You can’t tell whether a particular piece of music was composed by a woman or a man. But the music of women composers can have a certain sensibility that men will never grasp or achieve.

Did you have female colleagues in your composition class while you were a student? Has the situation changed?

There were some, but very few went on to a career. Many of them just disappeared. The proportion of female composers in composition classes is not that different nowadays, although the situation varies by country. Usually in France there are approximately 12 students, two or three of whom are women. In the U.S. the situation is better; in France the numbers have remained more or less the same. Then again, in the UK, there are more and more women composers in conservatories, many of them of Asian origin.

One thing that’s always puzzled me is the way that the history of women composers is taught. The names Clara Schumann, Fanny Mendelssohn, and Alma Mahler always come up—even though none of them were primarily professional composers, but were mainly known as the wives or relatives of canonical male composers. Why does the music world continue to focus on them, even though there has been, and still is, a significant number of independently successful female composers?

I think the problem is that women are relatively new in almost every field. There are more and more female composers, painters, writers…it will take at least a century before people get used to it. Meanwhile, just let them talk.

What do you think of the young composers of today? Do you have any tips or advice for them?

I find many of them a bit pretentious. They are too busy getting their music performed and only go to contemporary music concerts. They are not interested in other periods of music history. This is not a new situation. But I also notice that nowadays young composers are quite good at the business side of their careers, which is fine. My advice, however, is that a true artist should never have the feeling of having achieved something once and for all. Stay curious and worried! ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.

Comments are closed.