“I’m a happy woman, I’m a happy woman.” Meredith Monk’s sudden singsong was the first and only instance of actual words to be heard throughout an evening of vocal sound. This interlude, in which Monk’s voice was accompanied by soft piano chords, was one of the most touching segments of a Monk work that I have ever witnessed. Although at age 75, Monk’s voice is not sounding as smooth and precise as it once did, it seemed almost less self-conscious and unbounded. She didn’t shy away from the occasionally frayed or ragged note, letting them instead lend their textures to a multidimensional and fully expressive sound world—like wrinkles on a face that are not hidden behind makeup or plastic surgery.

Monk continued: “I’m a hungry woman.” “I’m a quiet woman.” “I’m an angry woman.” “I’m an honest woman, I’m a lying woman, I’m a dying woman.”

I’m used to trying to put Monk’s extraordinary wordless vocalizing on paper; this time, I scrambled to jot these simple yet contradictory descriptors down. The last one in particular stuck with me: although her vocal and gestural choreographies often veer into the realm of the childlike, here was Monk unabashedly making reference to her own mortality. It was one of many moments during the 75-minute work that affected me emotionally on a deeper level than any of her music I have heard. Monk’s voice was level and unassuming as she sang the words, demonstrating its bare beauty stripped from the context of her usual gymnastics of cooing and clucking.

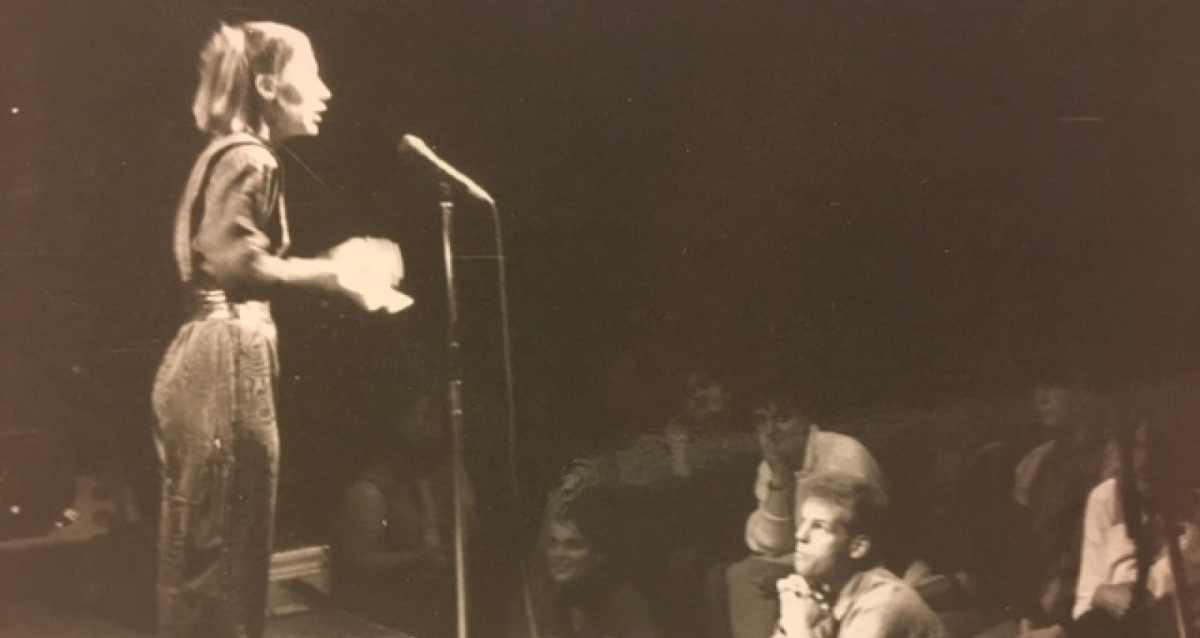

Meredith Monk, “Do You Be” 1971

Monk’s new magnum opus, “Cellular Songs,” indicates the precariousness of our global ecology through the flexibility and unpredictability of the female voice. The work was conceived, composed, and directed by Monk, with scenography by Yoshio Yabara and lighting design by Joe Levasseur. It was performed at the Brooklyn Academy of Music over the course of several nights earlier this month by Monk and four female members from her Vocal Ensemble: Katie Geissinger, Allison Sniffin, Ellen Fisher, and Jo Stewart, the newest member of the group. Although several male-identifying vocalists regularly perform with the vocal ensemble, “Cellular Songs” focuses specifically on the voices and embodied experiences of women, whether they be happy, hungry, honest, lying, or a combination thereof.

Video imagery projected onto the initially empty stage depicted a collection of overlapping and enjoined hands. The videos, designed by Katherine Freer, appeared at key moments throughout the performance: they were visual yet ephemeral evocations of the interconnectedness of human life, layered with overlapping human voices as Monk, Sniffin, and Geissinger walked onto the stage and began vocalizing a comfortingly familiar yet elaborate series of “heyos” and other vowels. As the hands faded from the audience’s line of sight, the trio managed to evoke a narrative using abstract movements and wordless sounds such as humming and panting. Once they were joined by Fisher and Stewart the movements became more exaggerated: five bodies spinning around the stage, their voices swirling through and across each other in a mélange of transient tones and textures.

The five women paced around the stage in costumes designed by Yoshio Yabara; their initial outfits of white jumpsuits and black combat boots were replaced about halfway through as each woman solemnly unzipped her suit and crunched it in a carefully constructed polyester pile in the center of the stage. Underneath the jumpsuits they were clad in white tunics and pants, which somehow seemed to glow in the dark as the women continued to whiz around the stage lobbing vowels at each other.

A rehearsal of “Cellular Songs” in Monk’s New York Loft.

“Cellular Songs” is meant not only to depict the fragility of the large-scale—our planet’s overall ecology—but also to trace this fragility all the way down to the most miniscule: the cells that make up each living being inhabiting our planet. Monk accomplishes this by spinning out her usual familiar repetitions into a series of physical and musical gestures that multiply like cancerous cells, or morph like the formless bodies of jellyfish. Although the sonic focus is on the human voice, “Cellular Songs” for the most part avoids human language, aside from “Happy Woman,” the interlude detailed above, which Monk describes as “a song of wisdom.” Monk’s narrative seems to advocate not only an acceptance of contradictions but, through the largely wordless piece, a decentering of “the human,” a sort of multinaturalist cooperation between human and nonhuman entities.

What sets “Cellular Songs” apart is not its intentionality but its execution. Many new music works strive for some version of what the BAM program notes refer to as “performance as life science.” I have always found these kinds of works to be a bit contrived, since surely their authors realize that the audiences consist not of climate deniers whose minds might change thanks to the ineffable glory of music, but the sorts of folks who will pay to sit in an assigned seat and be reassured that their views on climate change are “correct.” In these instances, I am always reminded of the limits of music-as-activism. Many ecologically minded composers merely reinforce the false binary between “culture” and “nature,” as musicologists like Ana María Ochoa Gautier have pointed out.

Monk takes a different approach, refusing this reductive technique that brings attention to the feminized beauty of nature only through a contrasting counterpoint of the masculinized, technologized beauty of art. Monk does not attempt the “sonification” of climate science or ecological catastrophe but rather the advocation of “care, comfort, companionship, and collaboration.” Her musicalization of ecological distress focuses on the simplicity of the voice rather than on numbers or technologies. Perhaps this is why a scene in which the five women congregate around the piano and plunk out mechanized punctuations to their vocalizations felt less effective than others. It is, after all, the voice that connects music to breath, air, and the environment.

Much more convincing was one of the work’s final scenes, in which the women intoned a series of vowel sounds while seated on stools in a circle, facing outwards away from each other but with their hands joined. Although I am not a fluent translator of Monkish, it seems that the interweaving and gradually lengthened vowel sounds, ranging from initial staccato “ha”s and “hee”s to elongated “hi”s and “ooh”s, were symbolic of the sorts of cooperation that can be built through touch, rhythm, and voice, not necessarily with human language or visuals. In the final scene, members of the Young People’s Chorus of New York City joined the five members of Meredith Monk & Vocal Ensemble on stage, humming and mumbling and finally collapsing into heaps of still-humming bodies curled in the fetal position on the floor. This visual was a stark reminder of Monk’s words—“I’m a dying woman”—and the circularity of the sorts of biological processes “Cellular Songs” is meant to evoke. Ultimately, Monk brings nature into her music just as she advocates bringing music—and care, and companionship—back into nature. ¶

Comments are closed.