For all her infamous name recognition, performances of Clara Wieck Schumann’s works are still puzzlingly rare. For decades I never questioned this; I bought the industry-wide indoctrination of “low quality.” But when I began to objectively look and listen, I realized Wieck’s compositions were filled with innovative tonal relationships, thematically unified structures, advanced motivic developments, and genre-forwarding architectures. The more I sit with her music, the more the ignorant, inbred assertion of her inferiority—within an art form that prides itself on intellectual taste—mutates to a stain of embarrassment.

A select minority of performers have pulled back the curtain of gender clichés to revel in the works of this masterful composer. Pianist Alexandra Dariescu speaks of the Piano Concerto in A Minor’s intricate harmonies, polyphony, and technical demands. Pianist Sharon Su praises Wieck’s subtle use of rhythmic shifts which hold the listeners’ attention in the Piano Sonata in G Minor.

Wieck is steeped in the tenets of Romanticism, her music containing poignant depictions of nostalgic yearning for actualization. Mezzo-soprano Helen Charlston tells me that Wieck’s song “Die Lotusblüme” is “one of the greatest songs ever written,” adding that the rest of the lieder in the Op. 13 set “are beautifully direct and intentionally personal. Her musical language has an amazing way of the natural world seeping seamlessly into the way that we feel about ourselves as people.” Pianist Ning Hui See says of the Piano Trio in G Minor, “It’s the kind of work that demands your attention. You have to give it the respect that you would give to Beethoven.”

At first glance, the blame for the lack of Wieck performances falls on the most high-profile offenders: the top tier orchestras who’ve yet to program her piano concerto; the major record labels who’ve neglected half her catalogue; the entire music publishing business with no collection of her complete piano works. But guilt-tripping the most visible culprits masks the chronic condition, a sickness our artform has not yet learned how to heal: the scars of a broken performance tradition.

When asked, “Did you study the Wieck sonata with a teacher?” Su responds emphatically, “Absolutely not.” She adds that her teacher “was mostly fine with it, as long as I didn’t stop doing the things he assigned.” She learned it on her own time. When she did bring the sonata to lessons, she got “very general help” and is familiar with reactions like “I don’t know what to do with this.” Su began playing the sonata in 2017 and recorded it in 2019. She says, “I still have yet to ever study with someone who goes, ‘I know this music, I know the style.‘” Other pianists had similar experiences. None were assigned Wieck’s works by a teacher or even knew of a piano professor who’d performed her works. “It’s not always because people are prejudiced,” See explains. “They’re just being responsible.… They’re trying to make sure you don’t get skewered by your panel.” She adds, “Juries will think you can’t play Chopin.” In the factory system, playing any piece besides the standards can pose a career risk.

Dariescu has had excellent teachers, but she doesn’t know of any who have assigned or performed Wieck’s work either. She’ll perform the Piano Concerto more times than Wieck herself this season, but has had to study the work completely on her own. So far, she says, with “every single conductor it was their first time doing it.”

Conductor Talia Ilan, who performed the Wieck Concerto with pianist Nadia Weintraub, tells me, “Everything we did was self-education.” Baritone Thomas Oliemans vaguely remembers a teacher mentioning Wieck’s songs, “but addressing them as ‘girl songs,’ as in: written by a girl, so best sung by a girl.”

Wieck’s status as an outsider from the canon functions, as Su puts it, like “a double-edged sword.” Going rogue from performance tradition unleashes artistic freedom but also self-doubt in an artform that worships historical correctness.

See calls it “a challenge that presents opportunity… I felt slightly trapped by the burden of recordings. I could play something that has no recorded legacy. I can put my own stamp on it.” Dariescu also appreciates that liberation from expectation. “Reading and understanding her style without any influences—I love that.”

But there’s also the added pressure to “get it right,” which they’re shouldering alone. “For so many people, this will be the only thing of Wieck’s that they hear,” Su says. “I’m worried that my failings as a performer will be read as hers as a composer. It’s real imposter syndrome stuff… It very much felt like a risk that I was taking.” “You’re not only having to defend her work,” See explains. “But also your own playing skills, your overall artistic image.”

The fact of Wieck’s name recognition—as a musical personality, if not as a composer—is similarly fraught. “On one hand, she’s got this built-in recognition, but on the other hand, that recognition is flawed,” Su says. See quotes musicologist Natasha Loges, who says that “the privilege of Clara Schumann’s name…comes with baggage.” In reference to Wieck introducing Johannes Brahms to his longtime publisher Fritz Simrock, Su calls Wieck the “power broker of the Romantic era.” She was not just a muse: “Clara is the answer to why we do what we do in terms of musicality, in terms of pedagogy, in terms of classical music etiquette.” Before she finally started playing Wieck’s sonata, Su had been fascinated by Wieck’s story for years: the legendary composer prodigy and virtuosa who thwarted the stigma of “lady composer” and the criticisms of her husband to write multi-movement works. The Priestess of Art who sacrificed promotion of her own compositions and dedicated the might of her fame and 60-year touring career to secure Schumann and Brahms in the canon rather than herself.

Once a performer has discovered Wieck and made the risky decision to program her music, the perpetual programming conundrum follows: To Robert, or not to Robert?

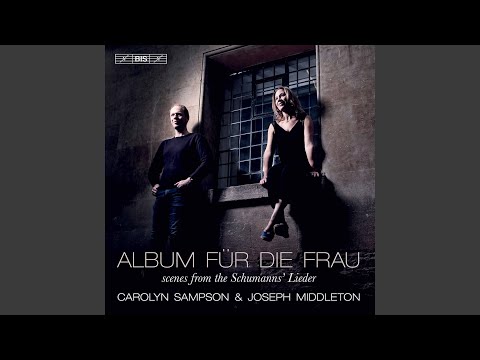

Wieck’s oeuvre is “great music, so you should be able to just program it on its own,” Charlston says. “But the weight of The Story and the history is so big that it’s really interesting to tell audiences.” For soprano Carolyn Sampson and pianist Joseph Middleton, The Story was the groundwork for their new recording, “Album für Die Frau, Scenes from the Schumanns’ Lieder.” “We start with the texts,” Sampson says. “Joseph basically sat and read.” He chose which of Wieck’s songs to use in their narrative alongside Robert’s “Frauen-Liebe und Leben.” Correcting some of the “baggage” played a part in their choices. “It’s really important for me that the woman continues after the death of her man,” Sampson adds, unlike the protagonist of Robert’s cycle. “Because that’s precisely what Clara did.”

The Odysseus Trio performs Wieck’s Piano Trio on a program themed around wives and husbands. “Clara’s trio certainly doesn’t need the crutch of being paired with her husband,” cellist Rosie Biss says. “Though there’s going to be an innate fascination with pairing them together from an audience perspective.”

As a conductor, Ilan felt it wasn’t fair for her orchestra to play only Johannes Brahms and Robert: “It puts Clara even more in the shadows.” She orchestrated two of Wieck’s lieder.

Since none of the musicians I interviewed learned of Wieck’s works in school, most came to her music through her husband’s. (With notable exceptions: Dariescu credits a performance of the Wieck concerto during the 2019 jubilee, and See heard a performance of the trio.) The majority have programmed Wieck alongside Schumann, proving what musicologist Susanne Wosnitzka of Archiv Frau Musik writes: “The fame of Robert can be a springboard to playing works by Clara.”

Because of this, separating Robert and Clara can be complex. Charlston and pianist Natalie Burch at first paired Wieck’s “Sechs Lieder,” Op. 13 with Schumann’s “Frauen-Liebe,” but they’ve since constructed new programs without him. Other performers never programmed Wieck with Schumann in the first place. Su considered pairing Wieck’s sonata with Schumann’s, “but then I thought, What purpose does that serve?” She played it with a Beethoven sonata instead. Dariescu has turned down invitations to play the Schumann concerto “so many times” because “it’s just not me.” Despite her repertoire of 60 concertos, “I’ve never ever performed it. And I don’t know if I ever will.” Instead, she likes to program the Wieck concerto with George Enescu. But a striking theme runs across all the musicians’ stories: They’ve had requests to perform Schumann, but no one got requests to perform Wieck.

There are more complications with choosing to perform Wieck’s pieces. Su encounters being pigeon-holed as a performer. “Having a niche is good,” she says, but people also forget she plays lots of canon repertoire. Dariescu admits of performing the Wieck concerto, “I wouldn’t be allowed to do this if I hadn’t already gained respect.”

Programming Wieck takes extra curatorial effort. “It’s not so much about what you play, it’s about how you present it,” says Su. “I do a lot of storytelling.” Most of the other musicians talk before or after Wieck’s music: some about her story, some about the compositional construction of her work, some about both. “I think the audience’s reaction is really, really important,” Dariescu says after her first performance of the Wieck concerto last month at the George Enescu Festival, with Ádám Fischer conducting the Basel Chamber Orchestra. “Everyone loved the piece,” she adds.

Convincing presenters involves both creative strategy and sheer tenacity. Dariescu will offer Wieck’s concerto as the first option. Sampson talks of being “fired up about this program.” See will give options for “four or five possible programs constructed for collaboration on Clara’s sonata.”

Despite this dedication, there is still progress to be made. According to Gabriella Di Laccio, founder and CEO of Donne, Women in Music, Wieck’s concerto was only performed by five orchestras in her worldwide study of the 2020-21 season. Su points to a cancellation of Isata Kanneh-Mason’s performance with the Los Angeles Philharmonic where a Beethoven concerto was subbed. Presumably no one else could be found to play the Wieck concerto. To which Dariescu responds, “There’s a few people playing this concerto. They just need to look for them.” All the same, “You can’t get just one or two performers championing music, you need a full scale buy-in,” Su says.

Research on Wieck by musicologists like Nicole Grimes at the University of California, Irvine is facilitating progress in the academic system. Grimes references two piano professors at her school, Nina Scolnik and Lorna Griffit, who’ve taught and performed Wieck’s trio for years, and they’ve also each taught Wieck’s sonata to two students. Scolnik gives credit to Grimes’s research that “has caught fire among the students and piano faculty. ” “For a real chance,” Wosnitzka writes, “We do not need flagship projects to succeed, we need a solid base.” She and Grimes both reference the lack of “balanced” music history textbooks. They also agree on reaching a wider audience and wanting researchers to be acknowledged.

As to whether Wieck’s status is on the upward trend or just leftovers from the 2019 jubilee celebration, Dariescu shrugs. “We will know if they program the concerto again. As soon as I get my first re-invitation with one of the conductors, I’ll let you know.” In any case, the journey to canonization for marginalized composers without a husband they made famous or a 200th anniversary to celebrate is even harder. “All we can do is just shout it from the rooftops,” Dariescu adds. “I think unfortunately we’ll always have to work for this.” But she shows no signs of fatigue. “It gives purpose in our lives. It makes you really want to get out of bed and do something.” ¶

Correction: An earlier version of this essay misspelled Natasha Loges’s last name. Additionally, due to a transcription error, the piece incorrectly attributed the phrase “Clara stenosis” to Ning Hui See.

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine, and we’re able to do so in part thanks to our subscribers. For less than $0.11 a day, you can join our community of supporters, access over 500 articles in our archives, and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

(PS: Not ready to commit to a full year? You can test-drive VAN for a month for the price of a coffee.)

Comments are closed.