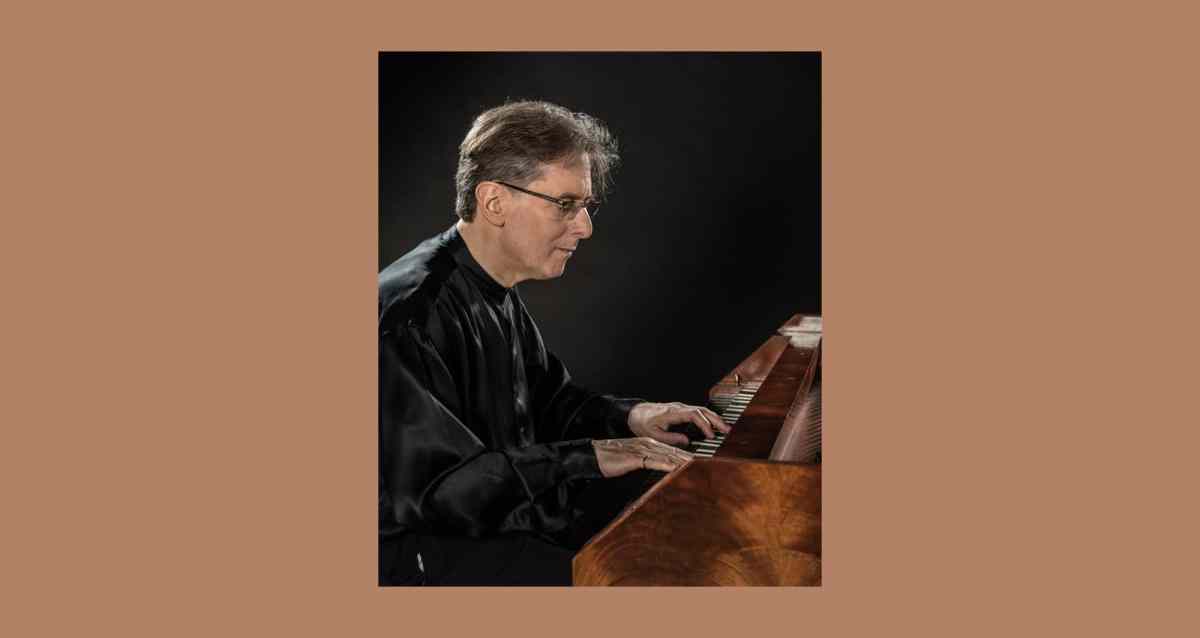

In June, I met pianist and musicologist Robert Levin at his home in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Complete editions of works by Mozart, Schubert, Beethoven, and many other composers filled his living room. As a musician, Levin has an almost uncanny ability to assimilate an oeuvre into the component elements of its style. It’s a remarkable process of distillation and abstraction that Levin demonstrates easily at his piano, toggling between similar passages from disparate pieces—especially by Mozart—both finished and fragmentary.

In 1991, Levin finished his version of the composer’s Requiem, which many critics consider the most convincing (even counting the 1791 version made by Mozart’s assistant Franz Yaver Süßmayr). In 2005, Levin completed the Mass in C Minor. We talked about these long settled—yet still omnipresent—projects; artificial intelligence in musicology; and the interpretation of contemporary music, while sitting masked in Levin’s living room.

VAN: You finished your completion of Mozart’s Requiem 30 years ago. Are there things you’d like to go back and change now?

Robert Levin: There’s never an ending to what one wants to do. More often than not, when I go to a performance and listen to it, I suddenly say, “Why didn’t I do that instead of this? Oh, dear…” I think about it as I stroll home after the concert and I suddenly say, “There’s a reason I didn’t do that.” It’s not that I failed to consider it; I considered it and I got rid of it.

The process [of completing the Requiem] was so demanding and so humbling, and I spent so many hours second-guessing myself, both in the process of getting these things on paper and then in thinking them over again in the various stages of publication. I came to a conclusion that in the end, whatever other revisions I might have carried out, they would almost all be the questions of this or that without necessarily producing a qualitative improvement.

Not infrequently, I’m approached by colleagues who themselves have undertaken versions of the Requiem, and who invite me to get involved in a dialogue about these things: “Why did you do this?” I have to say that, most of the time, I’m not very interested in it. I say to them, “Look, there’s no lack of respect from me about what you’re doing. If I were to discover that your version gives me more satisfaction and is more persuasive than mine, I’d be the first person to say, ‘Don’t play my version, play that person’s version.’” But I’ve been through the long nights already.

I don’t want to be wrong, but I don’t really want to be right either. I think this is a decision that posterity is going to make. It would be heartwarming to know that mine had withstood the test of time. In any case, there’s nothing much I can do about it. It’s a very humbling process. One learns so much about the nature of Mozart’s genius and so much about one’s own fallibility.

You’ve been studying the Requiem since 1966, when you first attempted a completion of the “Amen” fugue for a concert at Harvard. How did you progress from that youthful attempt to completing the whole piece?

In the autumn of 1987, when I was piano professor at the Hochschule für Musik in Freiburg, I got a call from the Internationale Bachakademie saying that Helmuth Rilling was going to be giving a seminar on the Mozart Requiem to his conducting students. He wanted them to have an insight into the whole problem of the Requiem. So I came and talked about the various attempts made to complete the Requiem, and the questions which are engendered by studying them and comparing them.

Several weeks later, I was back in Freiburg and I got a call from Bachakademie saying that the Maestro wanted to speak with me in Stuttgart. I went, and he commissioned me to do a new completion, saying that he had taken very seriously my critique of the other completions and that he would never conduct any of them because he didn’t believe in them.

Hearing the way I dissected those [other] completions and the criteria that I had used gave him the idea that I would be capable of doing a completion. Therefore he was willing to take that risk and proposed commissioning me for as handsome a fee as any he would give to a leading composer for a new work.

Did you feel ready?

I thanked him for his vote of confidence, but I said to him, “You know, in America, we say, ‘I may not be able to lay an egg, but I know a good one from a bad one.'” I then went on to say, “I also think that I am not the best person to do this. First of all, because I come from the wrong country. Mozart is the cultural property of Germany and Austria. In particular, because I have the wrong surname. I don’t think you really want to put yourself in the position of trying to be an advocate where there might be quite an uproar.”

You thought there could have been anti-Semitic backlash?

There could have been. It wouldn’t have been inconceivable. It might not have been expressed in an overt way, as such things often aren’t. Well, Rilling listened to all this and dragged—as he liked to do—on his cigars. He said, “You know, I thought you would say these things, and now that you have said them, which I not only thought you would, but hoped you would—that convinces me more than ever that you’re the person I need to do this.” I said, “I cannot tell you how touched I am by your confidence but the answer is no,” and I got in my car and drove off. He pursued me for two and a half years. He seemed to always know where I was. Finally, I thought it must be easier to complete the Requiem than to keep on telling him that I can’t do it.

I started to work and I would send him things in the process. I didn’t finish all the details until about three weeks before the premiere. Then I flew to Stuttgart, and during the rehearsals I was saying, “Let’s change the viola part. Let’s do this and that.”

Like a composer.

You could imagine that he would, at a certain point, say, “That’s enough.” Never did. He would say, “Sit within the orchestra,” or “Go out and listen and give me a thumbs up.” To this day, his advocacy is one of the most extraordinary moments in my life.

When I sat in the Hegel-Saal of the Liederhalle in Stuttgart, and they gave that performance—if you’ve ever heard a performance of sacred choral music in Germany, you will know that at the end of it there is a long silence. There is always the sense of faith and the sense of piety that intervenes before a visceral appreciation of the actual. It puts the integrity of the music in front of the virtuosity of the performance, which I think says something for the Germans.

It’s like after the second act of “Parsifal” at Bayreuth, where the audience doesn’t clap by tradition.

Exactly right. There was a huge silence. I was sitting there with my heart pounding. I had no idea what was going to happen. What ended up happening was pandemonium. It was an incredible ovation, people screaming “Bravo,” and so on.

At what point can you really feel comfortable inhabiting Mozart’s skin to the extent that you can undertake the project of completing his unfinished pieces? That feels like a lifelong task for me, one for which you can never be completely ready.

The first attempt I made to complete anything by Mozart was the “Amen” fugue from the Requiem. I was extraordinarily fortunate to have studied for a period of five summers with Nadia Boulanger. She ran a tight ship. You did four-part harmony and multiple-part counterpoint and fugue. She subjected me to the classic disciplines and gave me a mastery of voice leading for which I can take no credit whatsoever. I was just an industrious student who was young enough not to be too…intimidated. I mean, some of our students took tranquilizers before they went into the private lessons. She was fierce. She would put Stravinsky full scores on the piano, and if I didn’t, say, read them perfectly, I’d get punches in the ribs—literally, from this grandmother-age woman.

Nadia Boulanger gave me the discipline and the stylistic understanding to tackle something like [the Amen fugue]. She synthesized spiritual and technical understanding. She said that the art of being a teacher was to encourage a young musician to use fantasy and imagination and to take risks to find his or her own voice and beyond that to be utterly ruthless in questions of discipline. Boulanger ordained enthusiasm and discipline.

So after the Amen fugue, I got very interested in what other pieces Mozart left unfinished. I was stupefied to discover that there were 140-plus major torsos by Mozart whose abandonment has nothing whatsoever to do with their inferior quality. On the contrary, the fragments show more audacity, more fascination, more forward-looking character than the pieces that were finished. If Mozart had only lived to be 40, what would he have written? The answer is to be found in those fragments.

Doesn’t that make them harder to complete, if they’re more forward-looking?

This is one of the real obstacles, aesthetically. When you are trying to complete a piece by a past master, you are distilling that master’s habits, their rhythmic vocabulary, their harmonic vocabulary, their melodic vocabulary. Essentially, you are living inside a world which is defined by the 800-and-some-odd pieces that Mozart began and finished. Whereas Mozart isn’t held down by any of that. And to talk about Mozart’s style is a bit misleading, because you have to talk about his styles—in the plural.

There’s a remark in the foreword to your edition of the Requiem, where you’re talking about preserving a certain surprise. How can you, as a completer of his works, account for that unpredictability?

You have examples of the dialectic of how he does it in other pieces. If it happened only once, you think, well, it’s a one-off, and it would never happen again. But Mozart does often go off on these extraordinary tangents. Seeing Mozart do this in works both complete and incomplete is helpful, because it then gives you an idea of where to recognize what sets up such a thing.

I mean, you can see him turning a certain corner and heading in a certain direction. But to me the important thing is to understand the aesthetic of these moments of audacity or alienation and understand that they have to be one-offs. Because they have to be one-offs, you’re going to have to change something about them, which is risky.

That does sound risky.

[Levin demonstrates an “alienation ploy” from the String Quintet No. 3 in C Major at the piano and shows how he used a similar effect in his completion of the Clarinet Quintet in Bb Major.]

You can say, “Well, what gave you the courage to do that?” I answer, “The C Major Quintet gave me the courage to do that.”

Of course, once I use this particular bag of tricks a couple of times, you’re going to say, “Yes, of course.” Some of these things are ultimately unfathomable. Once one has analyzed, has dug in and understands the philosophy that underlies the decisions, then you see the difference between the skyline and the ground below, which I think is the most important thing about trying to do something which is more than mere style imitation. Because there are other completions where if you listen to any 30 or 40 seconds at a time, they sound fine. After you’ve listened to about two minutes, you get this funny feeling that you’re not getting anywhere.

When they try to get computers to compose music, that’s one of the first things that happens. The computers are working on algorithms. You can give the computer a motive and it will take the motive and it will develop it along a certain amount of the way. Will you feel, four minutes in, that you’ve gotten someplace? Are they getting hotter or cooler?

Do you think computers will ever be able to complete an unfinished Mozart work?

It’s not impossible. Well, it’s the old computer thing, GIGO: garbage in, garbage out. It’s not the computers that are at issue here. It’s the data that are being fed into the computers.

What if the input is the complete works of Mozart?

Again, that’s not necessarily a good idea because if it’s a piano sonata, as opposed to sacred work, the layers are going to be different.

You also perform contemporary music by composers like Bernard Rands and John Harbison. Is there a common thread between the composers that interest you?

What I look for are pieces that appeal directly to the emotions; that are expressive; that are capable of influencing our heart rate; that produce catharsis; that can have an ability to be shattering; that have an explicit emotional content. I played both books of the Boulez “Structures” because I wanted to see if I could do it. But, having done it, I didn’t particularly want to do it again, because it’s something that could be done just as easily by a computer. It’s a control freak piece. There’s nothing wrong with it—it can fascinate your intellect—but it does not nourish a sense of hope or fear. To me, that’s essential, and so I’ve gravitated toward composers whose music sends me an explicit message that I feel I am capable of transmitting to a public.

When I give commencement addresses, I sometimes say, “Your job is to keep people up at night.” You want to have them wake up at 2:30 in the morning, and suddenly remember, trembling with terror, a moment in your performance of a piece—whether it’s a modern piece or by Beethoven—after which life will never be the same. ¶

Comments are closed.