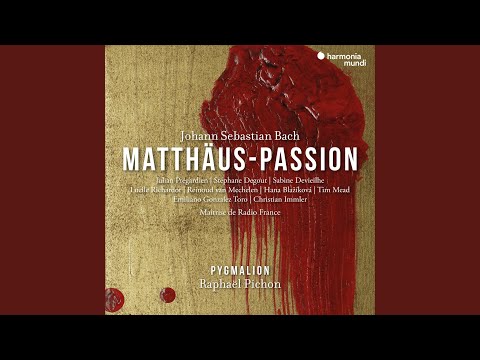

- Raphaël Pichon, Pygmalion, et. al.: “Bach: ‘Saint Matthew Passion’” (Harmonia Mundi)

- John Eliot Gardiner, Monteverdi Choir, English Baroque Soloists, et. al.: “Bach: ‘Saint John Passion’” (Deutsche Grammophon)

- Harry Bickett, The English Concert, et. al: “Handel: ‘La Resurrezione’” (Outhere Music)

In the Gospel of Mary of Magdala, a post-crucifixion Jesus returns to earth. He tells his disciples to look within themselves for inner peace, rather than to him, “for the child of true Humanity exists within you.” This does not go down in the way Jesus had expected with his followers; or perhaps it goes down exactly as expected: Everybody—excuse my Aramaic—loses their shit.

Everybody, that is, except Mary of Magdala, who tells her fellow disciples that she’d heard something similar in an earlier vision: “For where the mind is, there is the treasure.” Except her fellow travelers are left even more doubtful. Andrew doesn’t believe her. Peter wonders at Jesus choosing to speak with “a woman” in lieu of his followers en masse. Levi, however, comes to Mary’s defense, saying to Peter: “You are always ready to give way to your perpetual inclination to anger.” (I love it when a 2nd-century text predicts social media.)

I was reminded of this when reading the liner notes for Harmonia Mundi’s newest “Matthew Passion.” In an interview with Julian Prégardien—the recording’s acutely compassionate Evangelist—conductor Raphaël Pichon considers the long shelf life afforded to Bach’s patently Protestant oratorio: “Whatever our spirituality or culture,” he says, “all of us are confronted with our own mortality, our own search for answers. We all share its humanity.…In quite unprecedented fashion, Bach conveys and makes us feel the fragility and failings of humanity and describes a world gone awry, where love and faith are the only answers.”

Are there answers? I suppose if you’re writing for a Good Friday performance at Leipzig’s St. Thomas Church in the early 18th century, you’re probably obliged to fill in the Scantron dots for “love” and “faith.” But Bach’s “Matthew Passion” is also vaguely Rabbinical, Talmudic even, in how it leans into the questions versus the answers. The use of a double orchestra and double choir frames a volley of questions. The opening chorus, “Come you daughters, help me to lament,” is built around the call and response of some of the most basic questions: Who? How? What? Where? Sure, these merit responses: The bridegroom, like a lamb, his patience, our guilt. But these feel as much like placeholders for our own answers as like an answer key.

Pichon brings this out in an opening that’s quieter than other recordings, but highlights the distinct musical lines of each orchestra with echoing clarity as they weave around one another. To say the first few lines sound weak would be wrong; it’s not the quality of the singers, but rather a quality of the situation. The words “Kommt, ihr Töchter, helft mir klagen” are articulated like those first words you say after being stunned into silence, while you are still regaining your voice and your sense of language. You falter and crack, though in those cracks are the innate humanity of whatever tragedy has just passed. When one choir commands the other to see, and the second asks “What?” in response, it’s almost a whisper.

Conducting his ensemble Pygmalion, Pichon also enlists his soloists—with the exception of Prégardien—into the two chamber choirs. The characters in Bach’s passion play are part of the terrain, evolving out of the woodwork for their arias and recitatives. After hearing Lucile Richardot’s gusty, garnet-hued mezzo in “Buß und Reu,” you listen for its shades in “Ich bin’s, ich sollte büßen.” You then look for both the similar and offset strands in Tim Mead’s silkier and more serene countertenor. Skip from Richardot’s Part I aria and go directly to Mead’s solo in Part II, “Können Tränen meiner Wangen,” for a true side-by-side.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

Bach’s “Matthew Passion” obviously has its namesake Gospel, but I like to think of it as having more in common with the Gospel of Mary of Magdala, urging us to go within and live with more questions than answers. In some ways, this is an even more unsettling prospect than his “John Passion,” which is far more fire and brimstone and wears its heart on its sleeve. Perhaps this is why Mark Padmore wrote that “we need to approach every performance as though it were our first—and might just possibly be our last.” Hear it too many times, and it starts to sound more like Peter unwilling to hop off Mary Magdalene’s dick, rather than a flash-bang of emotional immediacy.

John Eliot Gardiner’s new recording of the “John Passion” restores some of that balance. Initially planned for a tour that was dashed due to lockdowns and travel restrictions, Gardiner led his Monteverdi Choir and English Baroque Soloists instead in a performance without an audience, in Oxford University’s cavernous and contemporaneous Sheldonian Theatre. The spacing within the hall, which Gardiner fashioned into a sort of courtroom for Christ’s trial, allowed for social distancing in an era of choral singing pre-mass-vaccinations, also creating a 360-effect where you feel thrust into the center of action. This time, however, Bach trades contemplation for chaos; this is the tragedy that prefaces the choked first lines of the “Matthew Passion.”

This was a dramaturgical intention from Gardiner, who recorded this performance less than three months after the January 6, 2021 Capitol Insurrection. “Given the then-recent events in Washington, it felt timely to present a piece that shows what can happen when the mob takes over,” he told Deutsche Grammophon earlier this year. It’s the sort of comparison that could sound artificial and shallow coming from another conductor. But Gardiner, who led an international tour of “L’incoronazione di Poppea” in 2017 that dragged Emperor Nero into the same spotlight as Donald Trump, knows how to finely draw and shade those parallels to create a supremely unsettling historical portrait.

Even Bach, however, can’t fully capture the range of expression around the Passion. As conductor Harry Bickett points out in the preface to his new recording of Handel’s “La Resurrezione,” the conceit of an Evangelist formally telling the story in third person—“often tailored to fit the author’s theological agenda”—and the chorus commenting as if it were another audience, is limiting, no matter the emotional direction provided by the composer. Handel’s oratorio abandons evangelism in favor of almost operatic characters playing out the story in real time. John is still there, but he’s not, as Bickett says, “the fire-breathing preacher of some Gospels; he is more the visionary, living off wild locusts and honey.”

It’s easy enough to picture tenor Hugo Hymas as a Biblical Big Lebowski, and his aria “Quando è parto dell’affetto” is one of the highlights of this recording, sung with tenderness and intimacy as Bickett draws out the presentiments of what would later become Sesto’s “Cara speme” in “Giulio Cesare.” It would have been interesting to see Handel’s edits to “La Resurrezione” had Mary Magdalene’s Gospel been rediscovered in his time; the comfort his Marys find in the loss of Christ doesn’t come from within their own connection to Jesus, but in consultation with John the Evangelist. Perhaps Mary would have been given the locusts and honey.

Still, Handel places much of his focus on the female characters in the wake of Jesus’s crucifixion: John is, alongside Lucifer, a supporting role to Marys Magdalene and Cleophas (a choice that did not endear Handel to the Pope when the work premiered in 1708). The message is clear: As much as we worry about our own mortality, our own death is less about ourselves and more about those we leave behind.

There are the inevitable arguments; “La Resurrezione” opens with an angel and Lucifer debating whether or not Jesus was brought down through the devil’s power. There are the abundant tears, shared between Sophie Bevan’s Mary Magdalene and Iestyn Davies’s Mary Cleophas as though the two were passing one seamless vocal line back and forth like a single drinking straw. There are fireworks of chaos and koan-like wisdom, as delivered in Davies’s rapidfire coloratura showpiece, “Naufragando va per l’onde.” At the end, there is acceptance, as grief is subsumed into the love that Mary Magdalene held for the one she lost. Bevan’s final aria, “Ho un non so che nel cor,” is breathless in its sense of relief and joy, balanced with trepidation.

Why do we keep recording these works? Harmonia Mundi, for one, had three strong “Matthew Passion”s before this latest salvo, including a recording featuring René Jacobs as countertenor and another with Jacobs as conductor. The idea of the audience as active participants was core to Peter Sellars’s production with the Berlin Philharmonic over a decade ago. John Eliot Gardiner had previously recorded the “John Passion”—twice. Perhaps it’s like “Degrassi: The Next Generation” and “Saved by the Bell: The New Class.” We need reboots and rerecordings because we can’t be relied on to hear one thing one time and make a lifetime of meaning from it. We need to cycle through these stories anew in order to locate and relocate whatever child of humanity it is that we have in each of us. ¶

Correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly credited Iestyn Davies as being on the “Saint John Passion” recording. He appears on “La Resurrezione.”

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.