The spiky, hormonal whiff of adolescence clings to Hector Berlioz’s “Symphonie fantastique” Op. 14. A classical music gateway drug, it stands for sophistication as clove cigarettes, Smirnoff Ice Green Apple, or the stems at the bottom of the baggie stand for sophistication, that is to say: not at all. All dark premonitions, opium, orgies, beheadings, and very deservedly unrequited love, it appeals to the young adult with an inkling that classical music is not as sexless as he’s been led to believe, but who also doesn’t know nearly as much about sex as he thinks. This might sound vague, so I’ll give, at some risk of personal embarrassment, an example: When I was in my teens I thought it would be really cool to program “Symphonie fantastique” on a concert, then advertise it with a poster reading “Sex. Drugs. Classical music.”

Berlioz’s own life indulges such pubescent fantasies. He wrote the “Symphonie fantastique” in an attempt to get Harriet Smithson, an English actress he’d seen in the role of Ophelia, to pay attention to him. (She didn’t hear it until two years later; they eventually married, but separated shortly after.) He railed against the “musical Philistines” of Paris in his ferocious music criticism. “My adolescent attempts at composition were tinged with deep melancholy,” he wrote in his memoirs. “Most of my melodies were in minor keys.”

“Symphonie fantastique” is a fixture both on orchestral seasons and on “most overrated pieces” lists on music forums and blogs. But the work has become a victim of its own aura, because beneath the Halloween kitsch are orchestrational innovation, rhythmic mastery, and melodic brilliance.

That first quality is the one most likely to make the “Symphonie fantastique” the object of serious study. It’s worth reemphasizing just how inventively Berlioz used the orchestra in the piece. Sure, the use of col legno battuto is famously bonkers. But the echo section between English horn and offstage oboe at the opening of the third movement, “Scène aux Champs,” is devastatingly desolate, particularly live, when you can almost perceive the sound waves making their way across the concert hall’s expanse. Although the idea of a through-composed echo wasn’t knew—in Monteverdi’s “L’Orfeo,” a singer representing the echo continually repeats the last words of the title character’s elegant lament—Berlioz treats the idea in a highly original way, using disjunct bits of motivic material and canon technique to create a profound ambivalence. We don’t quite know if the two shepherds are playing to each other or playing past each other. (The opening of “Scène aux Champs” ran so that the opening of “Tristan und Isolde,” Act III could walk.)

Not until “Rite of Spring” would a composer find as indelible a use for the bassoon as in the fourth movement of “Symphonie fantastique,” “Marche au Supplice,” where Berlioz allows the fan favorite instrument to run wild over the strings in G minor for 13 jaw-dropping bars. How many young listeners have sat up in their chairs at that moment and thought, Whatever that is, I want to do it? (More bassoonists in the world is always a good thing; we should be grateful to the composer just for that.)

If you’re looking for subtlety of instrumentation, Berlioz has you covered, too. After the English horn and oboe echo in the second movement, he doubles a pianissimo violin melody in the low range of the flute, giving it a memorable glint. Orchestral composers rarely figured out how to write for low flute because it’s easy to drown out. Berlioz, using soli violins with mutes and pizzicato violas and divided cellos, heard exactly what to make the most of that gorgeous sound.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

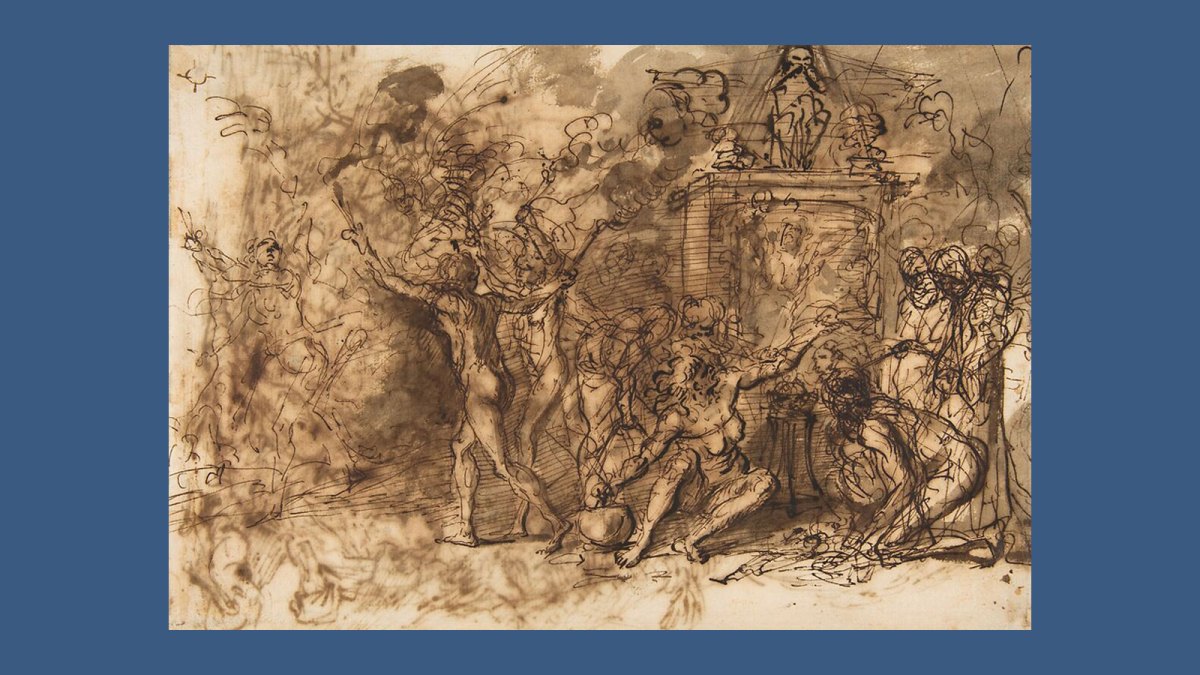

“Symphonie fantastique” is the kind of piece you can’t help but conduct along too. It’s hardly the most profound thing Berlioz learned from Beethoven, but he was still smart to repurpose one of the master’s favorite techniques: Just a shitton of sforzandi offbeats in a row. Not complicated, and yet when Berlioz uses it in an orchestral tutti passage at the end of the first movement, “Rêveries, passions,” it turns a pretty basic dominant pedal point into a passage that lifts asses out of seats. The same thing happens when he uses cello and bass offbeats to add syncopated punch to a statement of the “Dies irae” theme in the fifth movement, or accents the sixth beat of six-eight bars in the “Ronde du Sabbat.” The music limps and lurches; it dances, not gracefully, but having fun.

The real rhythmic innovation of “Symphonie fantastique,” however, takes place in the B section of “Marche au Supplice.” Berlioz writes simultaneous dotted-eighth-sixteenth notes, triplets, offset sixteenth notes, and onbeat quarters, and later eighth-note sextuplets against four-note groups of grace notes. The technique invokes a chaotic procession that has no leader and still somehow manages to move in a single direction: exactly what he was going for, yet something he couldn’t have imitated from anywhere. When contemporary composers write their orchestral textures with complex rhythmic subdivisions of three, five, 7-Eleven, it gives the mass a bubbling and organic quality, but they didn’t build that; Berlioz did. (Even Pierre Boulez, not shy about what he considered corny, recorded the “Symphonie fantastique” multiple times.)

Few pieces include so many earworms that have nevertheless managed to shrug off the hardest core commodification that usually comes for classical music’s good tunes. They are either too spare, like the idée fixe representing the distant lover; or too fragmentary, like the shepherd’s call; or too perverse, like the E-flat clarinet solo with its inappropriate, fleshy trills. (One exception is the ball theme, which easily outclasses Strausses.) For someone who has been going to classical concerts since their teens, it can be hard to listen to vividly melodious works like Beethoven Seven or the “Four Seasons” without feeling trapped inside a Classical Music to Do Yoga To playlist. Even after many, many listenings, the melodies in “Symphonie fantastique” retain their grinning strangeness, their wide-eyed creepines, their slightly mortifying sincerity.

Returning to “Symphonie fantastique” as an adult appreciative of the finer things (Schubert sonatas, Grasovka) is like seeing a particularly candid photo of yourself as a teenager. It can be hard to get past the literal pimples and the metaphorical witches’ warts. You might be surprised to find that there’s a lot to appreciate. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.