No, I didn’t attend any of the 11 concerts—four orchestral and seven chamber music—given by the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra during its residency in Shanghai at the end of June. Dubbed the orchestra’s “first residency” in China by the press and the China Shanghai International Arts Festival (CSIAF) which hosted the orchestra, around 135 musicians and administrators arrived in Shanghai by chartered China Eastern Airlines flight. Granted VIP access, members of the press and representatives of the concert promoter greeted the artists and the orchestra leadership inside the restricted area of the airport. A photo taken at the jet bridge of artistic director Andrea Zietzschmann, principal cello Olaf Maninger, principal viola Meidi Yang and pianist Yuja Wang went viral: A moment the audience has waited for seven years.

The orchestra had come to Shanghai two years later than originally planned; it’s now been seven years since its last visit to Shanghai, under Simon Rattle in 2017. Rattle and the orchestra were expected to visit Shanghai again in June 2022 to celebrate the 50th anniversary of diplomatic relations between China and Germany. That visit was announced in January 2021 after the company Wu Promotion signed an exclusive contract with the Berlin Philharmonic for its Chinese appearances.

According to a report from China Daily (which reads like a press release), the Berlin Philharmonic was planning to visit Shanghai every other year for an expanded residency program that includes orchestral and chamber music concerts, masterclasses, and pre-concert talks, because “it considers Shanghai, which is branding itself as the capital for performing arts in Asia, as an essential stage.” The report went on to claim that the announcement of the BPO’s Shanghai residency is “a shot in the arm for the global performing arts recession.” The news was released at that time, in 2021, because it was widely believed that China would lift some if not all bans on international travel and ease its draconian quarantine regulations towards the end of the year. Wu Promotion was also likely eager to impress the orchestra with its capability to facilitate the residency when COVID-19 was still a major concern. Perhaps the news was additionally announced in the hope that the Chinese government would have no choice but to comply once news of the high-stakes tour became public knowledge.

After Wu Promotion secured the contract for the China tour, the company was said to have pitched several potential local promoters. The Shanghai Oriental Art Center (SHOAC), which hosted the Berlin Philharmonic in 2005 and 2017, showed interest, but talks were discontinued by its new leadership. The Shanghai Symphony Hall, owned and managed by the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra, was another option, as by then it had hosted two residency programs with the Lucerne Festival Orchestra under Riccardo Chailly in 2018 and 2019.

The China Shanghai International Arts Festival (CSIAF) emerged as the strongest bidder. CSIAF (or ArtsBird, as it’s often called, because its logo looks like a bird) is an annual arts festival that primarily runs from October to November on the major stages in Shanghai, with satellite projects running in cities as far as Harbin. Under the auspices of the Ministry of Culture and Tourism and the municipal government of Shanghai, it presents performing arts including music, theater, drama and dance. It also hosts an international performing arts fair, exhibitions, and a professional conference. But the festival only hosts a trickle of its own programs, and often brands projects run by other promoters and venues as its own. Aside from the festival line-up, the festival’s administration runs programs assigned at the ministerial level. “The Age of Our Times,” a concert series featuring the best orchestras and new commissions, resulted from a direct order by the Publicity (read: Propaganda) Department of the Chinese Communist Party and was run by the festival’s administration.

The 2022 Berlin Philharmonic tour was canceled due to travel restrictions and new lockdowns. Post-pandemic Shanghai needed the orchestra to certify its rise to the status of “Asian performing arts capital,” a political campaign first set out by the municipal government in 2017 with its “50 Guidelines for the Culture and Creative Industry”: a policy with matching funds aiming to raise output from the cultural and creative sector and make it account for 18 percent of Shanghai’s gross domestic product by 2030. The planned Berlin Philharmonic residency fit perfectly.

None of this happened. The COVID restrictions only got more severe in Shanghai and were not eased until December 2022; the government didn’t make an exception for the orchestra. Diplomatic celebrations went ahead, including with a concert at Philharmonie—without the Philharmonic.

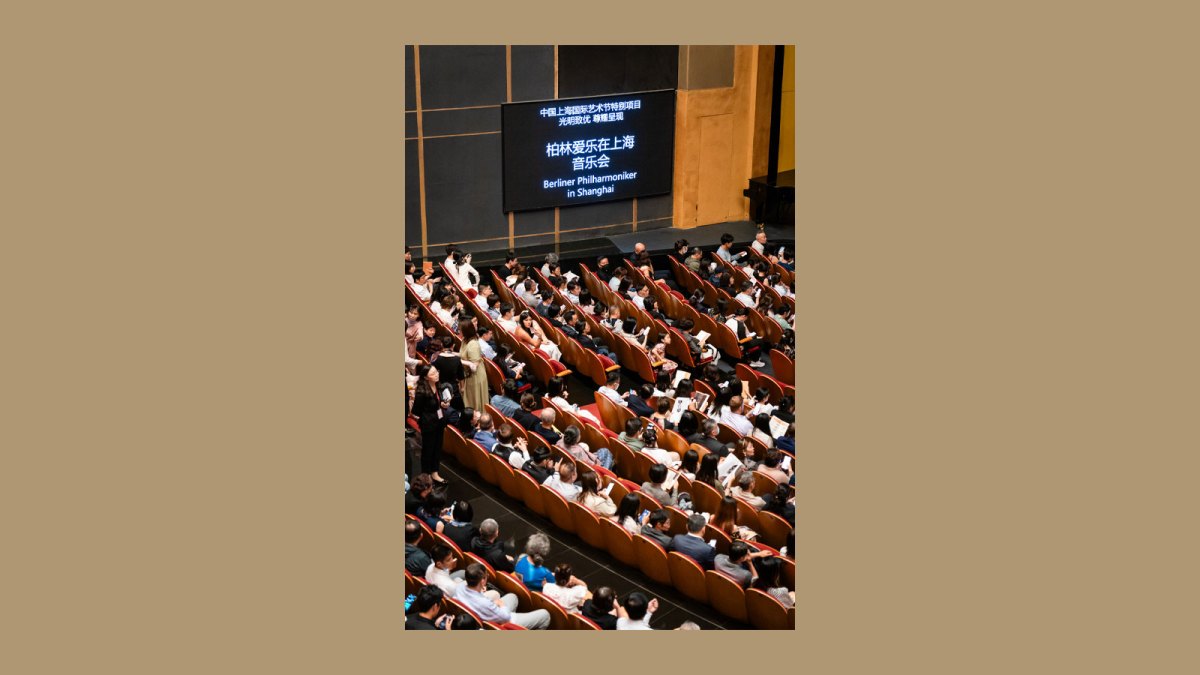

The residency of the Berlin Philharmonic has been painted as both an artistic triumph and commercial success by the Chinese press, made up almost entirely of propaganda mouthpieces. The orchestra’s fourth visit to Shanghai since 2005, often rendered by media as its “only stop in China,” is widely believed to show that Shanghai remains an open and charismatic port, and China retains its supremacy in the classical music market.

The data may show otherwise. Some 6,000 tickets were sold out in a mere five minutes when the box office opened in April (over 40 percent of ticket buyers were either from overseas or from other regions in China), but that is not necessarily just a reflection of the Berlin Philharmonic’s renown: The price for the best seats went down from 4,000 yuan during its previous visits to 2,980 yuan, thanks to municipal funding that covered most of the 24 million yuan total cost. (Each orchestral concert cost 6 million yuan.) The Philharmonic staged four orchestral concerts with Yuja Wang and seven chamber music concerts, plus open rehearsals, masterclasses, lectures, charitable events and outreach programs with local orchestra musicians.

The orchestra’s visit was conceived as a morale boost for a sluggish musical economy, as shown by shrinking piano production and sales figures, and a waning willingness for kids to learn an instrument, once the dominant force propelling China’s classical music market. Publicly funded orchestras and conservatories have been subject to cuts of 30 to 50 percent in their annual subsidies. For example, the budget of the Beijing Modern Music Festival (BMMF), China’s contemporary music flagship presented by the Central Conservatory of Music, was cut from 3 million yuan to 1.5 million yuan this year, making the 2024 edition the worst funded since its inception.

On its website, CSIAF lists 15 sponsors, ranging from Volvo to Turkish Airlines. The biggest single patron remains the government, as with all the publicly funded arts institutions in China. The title sponsor of the Philharmonic’s residency in Shanghai is Bright Dairy and Food, a state-owned company listed in the Shanghai Stock Exchange with a revenue of 26.5 billion yuan in the fiscal year of 2023 (down by 6.1 percent from the previous year). The company is recognized as the Strategic Partner of CSIAF. Because it is a government asset, it would be impossible for it to sponsor a project not approved of by the government.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

The stakes for the Berlin Philharmonic’s Shanghai residency were too high for failure or even second opinions. In an interview I did with Chinese online portal The Paper, I recounted my past experiences listening to Kirill Petrenko live in Munich and Berlin, including his inaugural concerts as chief conductor both in the Berlin Philharmonie and at the Brandenburg Gate in 2019. I went on to complain that the orchestra failed Chinese composers by not performing any music by living Chinese composers in the four major concerts from its residency program. My complaint was removed before publication.

Most of the Shanghai press failed to address the lack of Chinese music in the program. Instead, they portrayed how obsessed the orchestra musicians were with Chinese food. “Gyoza, pan fried buns and soup dumplings are everyone’s favorite,” Philharmonic concertmaster Noah Bendix-Balgley was quoted as saying by The Paper. With one exception: Yicai (First Finance) noted on June 25 that the “Berlin Philharmonic has brought contemporary music to China during its previous visits, notably works by Unsuk Chin and Toshio Hosokawa. Music by Chinese composers has not been programmed for this residency. They are not selected.”

The orchestra probably performed Unsuk Chin and Toshio Hosokawa in China not because they are Asian, but because their music is exceptional. The Belin Philharmonic is notorious for engaging only the best musicians, but also the best soloists, the best conductors, and the best composers. Still, there are more leading Chinese composers represented by international publishers like Universal Edition, Sikorski, Boosey & Hawkes and Schott Music than ever before. Works by Tan Dun, Du Yun, Bright Sheng, Huang Ruo, Ye Xiaogang, Guo Wenjing, Shen Ye, Chen Qigang, Zhu Yiqing and Ihsan Abdusaram, to name a few, are performed by the likes of the New York Philharmonic and Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia across several continents. Their music has been recorded and released by DG, Wergo, BIS, Ondine and other major labels. The question is whether the absence of music by Chinese living composers is the result of arrogance or ignorance.

Most likely, local promoters never suggested that the orchestra feature any living Chinese composers. One orchestra source said those promoters just took whatever program the orchestra was offering. When asked about this, CSIAF initially did not respond to my request for comment. When pushed, its press office asked me to “stop making guesses.”

This is particularly strange since CSIAF, an annual international festival, has usually opened with new commissions in its previous editions, and frequently trumpets young composers and their works. Professor Ye Xiaogang, the founder and artistic director of the BMMF, whose work “The Genesis” was commissioned and premiered by the CSIAF in its opening in 2018, even asked me to schedule a private meeting between him and the artistic leadership of the Berlin Philharmonic in Shanghai to introduce Chinese composers’ works. During the residency, CSIAF strayed from its own programmatic priority of introducing living Chinese composers and their works and, as a public institution, failed to promote Chinese culture when it was needed.

On June 27, I departed for Harbin, a two and a half hour flight from Shanghai, to catch the world premiere of Huang Anlun’s Symphony No. 9, performed by Harbin Symphony Orchestra under the baton of Muhai Tang. Muhai Tang remains the only Chinese living conductor who conducted the Berlin Philharmonic. That was in 1983. I hope that the next time the Berlin Philharmonic returns to China, it shares the stage with Chinese conductors and music by living Chinese composers, to show that it takes Chinese culture—dumplings aside—seriously. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.