The Met Opera’s new production of Bizet’s “Carmen” stars trucks. Or rather tractor trailers, ready to move goods. In the first act, which the libretto sets in a Seville cigarette factory, workers crowd around a loading dock, loading boxes into a trailer whose destination is unknown. In the second act, Carmen and her smuggler gang have absconded with one, whose contents are still mysterious. In the third, we have reached a crisis: the truck is now on its side, the supply chain disrupted.

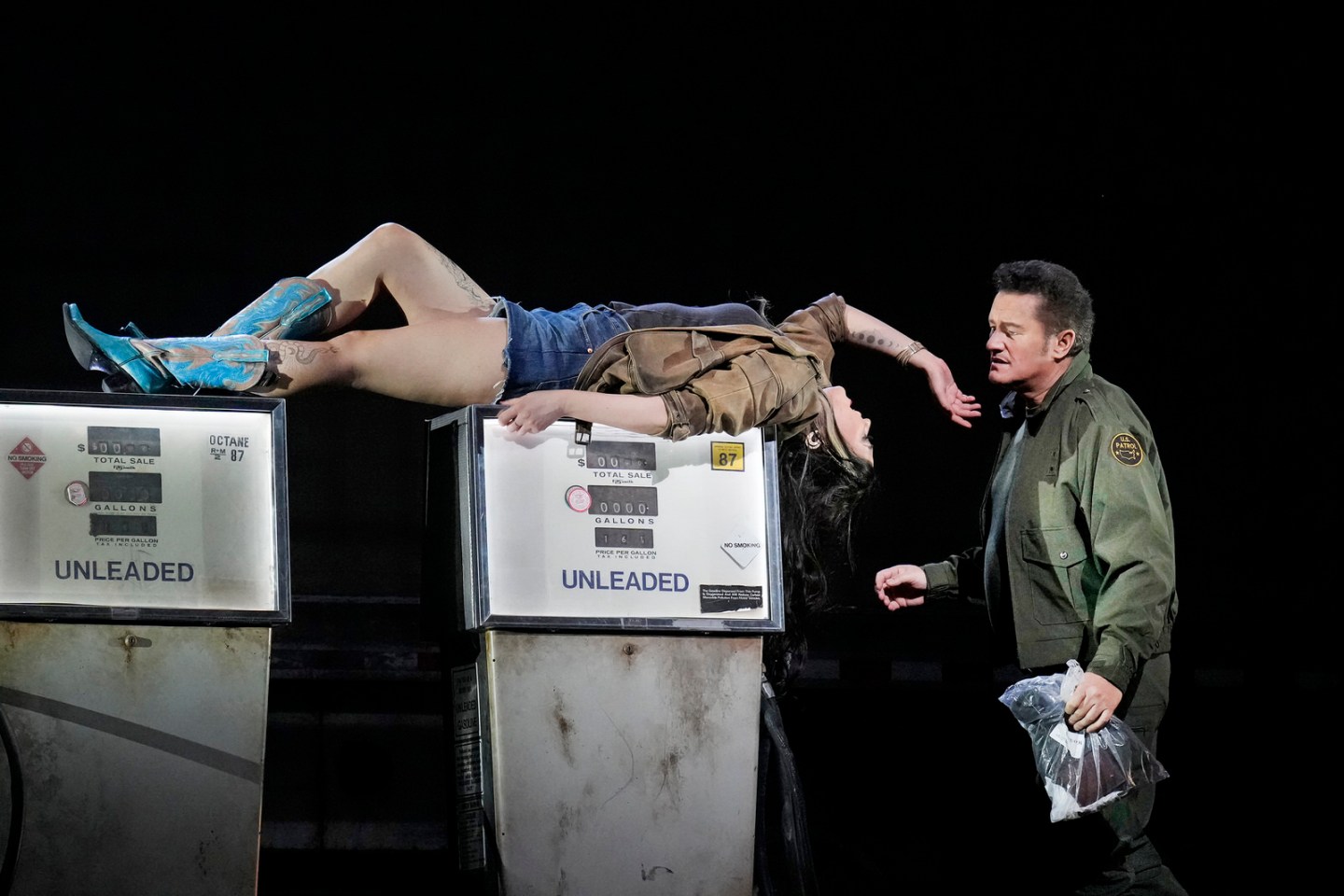

The production, directed by Carrie Cracknell and which premiered on December 31, is set in contemporary America, its images of blue vests, militarized guards and rodeos vaguely suggesting the U.S.-Mexico border, physical labor, and the rural South. The characters are isolated cogs in the gears of capitalism, the mysterious boxes they load and unload their only link to another world. Similarly, last season, Simon Stone’s production of Donizetti’s “Lucia di Lammermoor,” an opera about a woman whose forced marriage robs her of her sanity, took on today’s Rust Belt despair: a pawnshop, face tats, the suggestion of opioids.

Why has the Met, a literal gilded temple of European art, started staging middle American malaise?

I am not the first to ask. Zachary Woolfe of the New York Times, for one, isn’t happy about it. “There’s something depressing, even corrosive, in taking such a superficial glance at our fellow Americans,” he wrote, calling the “Carmen” production’s image of “flyover country” glib and exoticizing. Perhaps we don’t expect better from the Met than opera’s take on Hillbilly Elegy. But why can’t we?

Historically, opera has been primarily an urban phenomenon, found in big theaters in big cities, for which rural spaces have always had symbolic resonance. In the late 19th century, northern Italian audiences thrilled to the bloodthirsty screams of southern Italian peasants in verismo operas like “Cavalleria rusticana.” In 1935, the Black singers of “Porgy and Bess” adopted a Gullah dialect written by two white librettists for a New York audience. “Carmen” itself is a story of a Roma woman and “Lucia di Lammermoor” trades in a romanticized Scotland, though the Met stagings don’t really engage with those elements.

Nonetheless, in these productions, the Americanized worlds of “Carmen” and “Lucia” seem hazy. Is it because something sung with an operatic vocal technique, in a foreign language, will always seem “other”? That doesn’t seem to be what either Stone or Cracknell or their set designers Lizzie Clachan or Michael Levine were trying to do. The mismatched and torn clothes, the trash, the grime; all are fetishizations of the signifiers of small town American poverty. (One thing they don’t manage is the pervasive influence of evangelical Christianity. I wanted to add the “SHACKLED BY LUST?” billboard I’ve seen just outside Tulsa, Oklahoma.) But the visuals of both productions suggest naturalism, an unvarnished reality that the direction of the singers never manages to meet. Instead, the cast’s characterization is full of the International Opera Acting gestures of extended hands, clenched fists, and decisive walks across the stage. Don José kills Carmen with—spoiler alert, I guess—a handy baseball bat. Why is there a baseball bat at a rodeo, where the last act is set? I don’t know. Because America, I suppose.

Unlike a more classic European operatic takedown of capitalist America—like Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht’s brutal “Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny”— these productions seem committed to imitation rather than meaning. They never elevate their scattered details to the level of myth. The productions are a collection of curios, a dress-up that seems imposed from without.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

It was not ever thus. For all its aristocratic entanglements, American opera’s history had a populist moment back in the nineteenth century that stretched well beyond urban spaces. Musicologist Katherine Preston’s 2017 book Opera for the People offers a tour of a vibrant 19th-century culture of English-language opera in America. It was much less visible than the ascendent high culture of foreign-language opera, whose reputation was for elite exclusivity (see one of our other great documents of 19th-century social history: HBO’s “The Gilded Age,” season two), but it was prolific and popular. Those companies were often run by women, catering to a more middle-class audience than the Met, which from its creation in 1883 was an institution of (economic, racial) exclusion—new money instead of the rival Academy of Music’s old, but always money.

Small towns in America are still dotted by theaters marked “opera house.” Their definition of “opera” may have been a bit broader than what we now recognize, sometimes extending to local takes on Strauss’s “Dance of the Seven Veils” from “Salome” with less avant-garde underscoring, but not as much as you might think. Soprano Emma Abbott, one of the impresarias considered by Preston, toured with her English-language productions across the nation. In her 1884-1885 season alone, she visited, among other places, Ft. Wayne, Duluth, LaCrosse, Denver, Salt Lake City, Galveston, Waco, Topeka, and Little Rock.

One of her most famous roles? Lucia di Lammermoor. Of her 1881 performances in Denver, a local music critic wrote in the Daily News that she was “original and strong, and… full of quiet but intense dramatic force… Miss Abbott surpasses all of her competitors.” In other words, not only did the city have a Lucia, they had enough Lucias to compare with each other.

It didn’t last. Around the turn of the 20th century, the U.S. experienced what historian Lawrence Levine termed “the fragmentation of American culture,” in which the “choices and freedom” of the 19th century—and their freewheeling audiences—were gradually supplanted by a more hierarchal culture given the charming phrenological terminology of high-, middle-, and lowbrow. In 1850, the operatic soprano Jenny Lind toured America with P. T. Barnum to sensational success. But while she once sang (of course) “Lucia di Lammermoor,” when she opens her mouth in the 2017 movie musical “The Greatest Showman,” she belts out a pop ballad, “Never Enough,” with a voice provided by an alum of “The Voice.”

I’m not here to claim opera as innately populist or urge for RETRVN. Musical styles change. But the loss of the 19th century’s diversity in favor of a hierarchal consumer market doesn’t seem like an improvement. In the 20th century, the radio and middle class fueled a renaissance of the classical canon, when the likes of Leonard Bernstein, Marian Anderson and Luciano Pavarotti reached a wide audience. But classical music now carried cultural and symbolic capital; its mission was didactic and “uplifting.”

Even the Met used to tour the U.S. They only stopped in 1986, though they never visited the smaller cities Emma Abbott did. Now their presence is felt through the Live in HD broadcasts, whose impact on small-town opera remains disputed. Some have accused the broadcasts of leeching their audiences—unreasonably raising their expectations for spectacle and stars, and stealing time and donations from smaller companies. Others have called it a democratization of opera for a wider audience. But it’s not a wider audience for opera. It’s a wider audience for the Met.

In the first scene of Cracknell’s “Carmen,” some of the workers loading and unloading those trucks wear blue vests. Until recently, I lived in Northwest Arkansas, and those blue vests mean only one thing: Walmart. We in Fayetteville were 25 miles from corporate headquarters in Bentonville. (My experience of the South was—like it is for many—more one of suburban sprawl than rural decay.) Some people, with concerns both local and global, try to avoid stepping foot in one of the six Walmarts in our city of 100,000 people, but even if you manage that, you still encounter the Walton family (of Wal- fame) on a daily basis. They underwrite most of the region’s culture and institutions, like the gigantic Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, as well as the local bike paths, the airport, the art and business schools at the university where I taught. They are a fact of life, especially if you like opera.

In 2021 I saw Lithuania’s Venice Biennale pavilion opera installation, “Sun & Sea,” in Bentonville, courtesy of the museum’s contemporary branch. I talked to some people there and none of them lived in Northwest Arkansas. The piece is about climate change and I spent most of its open-ended running time preoccupied with the irony of its Walmart support. I helped produce several operas, all Arkansas premieres, at the Walton Arts Center in Fayetteville (also home of the Artosphere festival and orchestra). The Waltons often made life in Arkansas more pleasant for middle class transplants like me who tended to hang out with other transplants and complain about the lack of good Indian food. (Last summer, I got a new job and moved to Philadelphia. I haven’t been in a Walmart since.)

But there’s a cost. As Olivia Paschal has recently written, new development has also often come at the cost of homegrown, more grassroots cultures. The Waltons brought me that opera and helped me bring Nico Muhly’s music to Arkansans, but the Walton Family Foundation is one of the national funders of the charter school movement, a threat to our already imperiled public school system. Their political donations in Arkansas and beyond have led directly to laws endangering trans people, women, people of color, immigrants, and many other groups who already are among the most vulnerable. And it goes well beyond philanthropy and politicians: A 2006 study found that communities with a Walmart had higher poverty rates than those without. More recently, a New Republic investigation found worker safety issues that allegedly led to the preventable death of an employee. In 2020, Bernie Sanders himself commissioned a report that found the profits of Walmart were subsidized by the public assistance given to their poverty-wage workers.

In other words, those luxuries and operas for Walmart’s managerial class and local intelligentsia are underwritten by their exploitation of the overwhelming majority of their work force—the people who the Met has put on stage but whose real-life counterparts will never get to see the opera themselves. Those trucks in “Carmen”? Ultimately, they’re funding your opera, in the broad sense. As far as I can tell, the Waltons themselves haven’t given any money to the Met, but the enterprise is supported by the same larger philanthropic ecosystem. Extraction from the lowest rungs of labor is what has underwritten their simulacra’s appearance in “Carmen” and “Lucia.”

Stone’s “Lucia” originally planned on taking on the opioid crisis. It doesn’t seem to have made the final version; only the suggestion of it remains around the production’s margins. Even that much made me think of one of the most beautiful and powerful examinations of the entanglement of social crisis and philanthropy: Laura Poitras’s 2022 documentary film “All the Beauty and the Bloodshed,” a portrait of the art and activism of photographer Nan Goldin. A recovering opioid addict, Goldin leads a movement against Sackler family, founders of Purdue Pharma (the producers of OxyContin). As an artist, her primary target has been the galleries named after the Sacklers; in 2021, the other Met—the museum—removed the Sackler name from several spaces.

When I was in Arkansas, I taught aspiring opera singers in my musicology classes. Most could count the number of professional opera performances they had seen on one hand. Few or none had the advantages common in major music schools in the Northeast: the pay-to-sing summer festivals, the pre-college lessons, the pianists, the piano lessons, even a piano itself, the language classes, the travel. Sustainable careers in opera are too often a luxury only the wealthy can afford, and Arkansas’s isolation only compounds the difficulty.

When I was a grad student near New York, my Ivy League university often gave me free tickets to see opera at the Met. That’s how I saw the previous “Lucia” production, and their two previous productions of “Carmen.” But Arkansas students, some of whom actually lived a version of the real life that these two stagings so luridly explore, were unlikely to see it live, much less be the people performing it themselves. I am aware that I’m the one writing this essay when perhaps it should be by one of them.

There’s also the question of what these productions can’t show. Both “Carmen” and “Lucia” had diverse casts of singers, with people of color in multiple major roles. But norms prescribe color-blind casting, preparing these productions for whatever soprano or baritone is available to be dropped into the opera on a nightly basis. An opera production of a frequently performed warhorse like “Carmen” is created to be a flexible and durable item, functional in any casting configuration. That doesn’t mean that the audience doesn’t see the singers’ racial background and that it doesn’t add meaning to any given performance—as musicologist Naomi André has argued, there is no real colorblind casting. But it does mean that these productions can’t, structurally, be about race. In order to accommodate whomever the Met chooses to go on as Escamillo that night, their ability to take this on is circumscribed. And any attempt at a sociological vision of the American South without race is always going to feel incomplete and weak.

It’s ironic, because the Met’s greatest artistic and box office successes in recent years have been their stagings of recent operas by and about Black Americans: “Champion,” “Fire Shut Up in My Bones,” and “X: The Life and Times of Malcolm X.” “Carmen” and “Lucia” tend to reveal the Met’s limitations, while those productions suggested a genuine renewal of artistic energy and expansion of their audience (even if most of these works had already been performed at other opera houses in the U.S. that have been doing the work for much longer). If there seems to be something uncomfortably transactional in this turn—the Met’s newfound diversity in programming has earned it great press that has, for the time being, made us forget the previous music director’s alleged sexual abuse of children and also the fact that it was still doing blackface into the late 2010s—it has come with the creation of genuinely compelling art and opportunities for artists too long unrecognized by what remains America’s most famous opera house.

There’s something paradoxical in the very concept of these productions, which for many of the Met’s audience members registers as “Eurotrash,” a term that both describes a somewhat clichéd aesthetic of aggressive modernization of canonic work and, often, audience’s reactionary attitude toward such stagings. And they’re both directed by foreign directors, though neither British Cracknell nor Australian Stone quite fit the continental Euro image. That might not matter if their productions had something to say, but would someone who is themselves from small town American poverty be better equipped to represent it? At least a director with more evident interest in the complexities and variation of the U.S. outside New York might be able to bring it to life with more dramatic specificity.

The Met has, historically—even in “The Gilded Age” era—looked to Europe for operatic prestige (they commissioned Puccini! twice!), which is part of what makes the series of Black opera productions so exciting. In “Carmen” and “Lucia,” the company claims to have offered American transformations of canonic works. But for many of their audience members, they don’t register stylistically as a domestic effort. The Met aesthetic is instead one of camels and monumentality, typified by productions by Franco Zeffirelli (not an American, I know) and their opulent displays of wealth. Yet both are, in their own ways, embodiments of the Met’s integration in a system of funding where money always flows upward. I would love to see something subversive in these stagings; something of the machine turning inward to critique itself. I would love to see in “Carmen” and “Lucia” the freedom that Goldin ascribes to herself and her friends in “All the Beauty and the Bloodshed”: “rebels running from America, living out the life they needed to live.” But I’m afraid these stagings merely illustrate how far we still have to go. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.