When I first heard the music of Tom Johnson at a concert in Basel in 2013, I was immediately struck by its humor and unassuming simplicity. In contrast to the weighty works of the late 20th-century European avant-garde, Johnson’s music was a breath of fresh air. There were no hidden layers. It was transparent and legible. It was what it appeared to be on its surface—nothing more, nothing less.

I was surprised to learn that Johnson, an American composer, had been living and working in Paris for over three decades. I knew that French institutions were generally unsupportive of music made with such minimal materials—just ask Éliane Radigue. The more I learned, the more I was inspired by the rich creative life that Johnson carved out for himself, despite these obstacles, and by what his story meant for me as a young American composer looking to Europe for possibility.

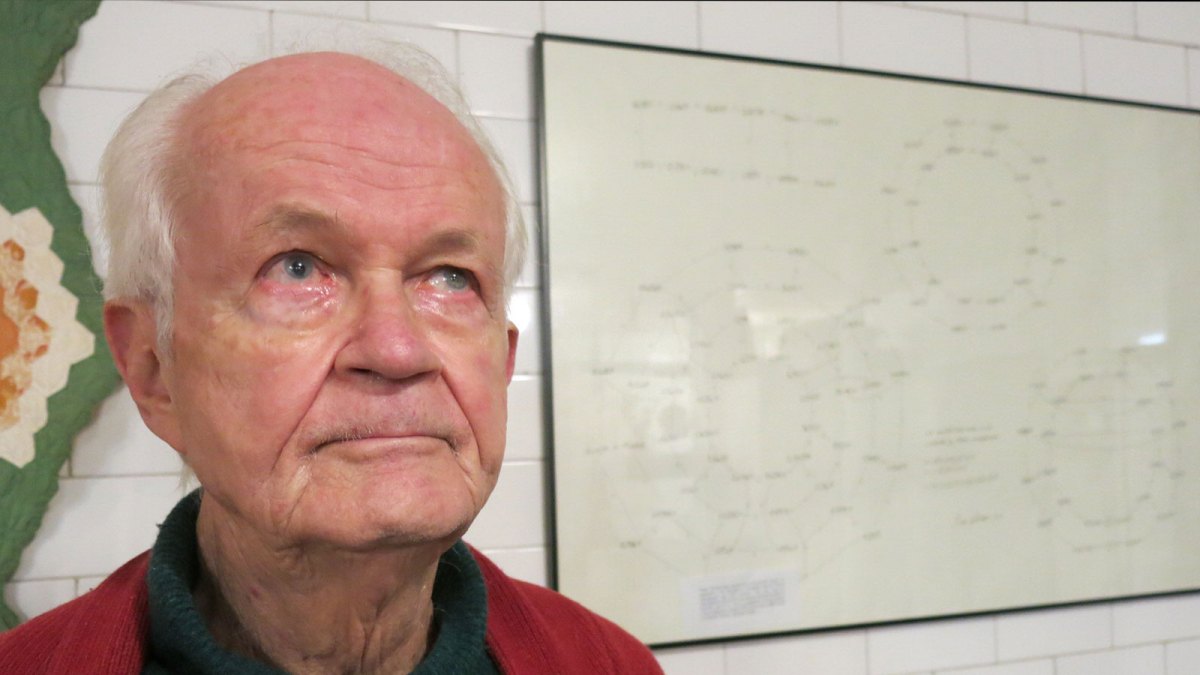

I visited Tom Johnson at his apartment, a short walk from Place de la Bastille, in May 2023. We spoke about musical humor, the minimalist takeover of New York, and our mutual admiration of Scarlatti.

VAN: Can you tell me a little bit about the musical milieu in 1970s New York when you were a critic writing for The Village Voice? Whose music most influenced you at that time?

Tom Johnson: I remember Terry Riley’s music. I loved “In C” and I knew that record well. More important for me though was Steve Reich’s music, when he was composing with systems like in “Drumming.” I loved that piece and wrote a very positive review of it. I was attracted to this idea of music for pieces of wood or percussion made of very simple algorithms. I later wrote a lot of simple “knock on wood” percussion pieces inspired by this.

Why do you think so many composers in New York started writing music built on simple repetitive structures around this time?

A lot of this was a reaction to the post-Webern movement centered around Columbia University with Charles Wourinen and The Group for Contemporary Music. This was the only type of music that those guys performed, and they were getting all this money to do it. But when The Kitchen opened in 1971, that became a place for downtown music. Very soon, The Kitchen was getting bigger subsidies than The Group for Contemporary Music, and bigger audiences too! So that encouraged us. We were against complexity, the pretension of it, and the small audiences. We wanted to make music that people wanted to hear.

Why did you choose to leave journalism and move to Europe?

In 1979, I debuted my “Nine Bells” in Paris as part of the Festival d’Automne followed by well-received concerts in Italy, Belgium, and the Netherlands. Around this time, Europeans were becoming interested in American minimalism, especially after the 1976 premiere of Philip Glass’s “Einstein on the Beach.” Unlike those in the U.S., European radio stations actually compensated composers and there were many well-funded festivals and art centers too. And so I thought I could potentially sustain myself solely through my music if I were to move to Europe.

But why did you choose to settle in Paris, where frankly, music like yours has never been institutionally supported?

I enrolled in a seminar at IRCAM in 1982 and met many wonderful people that year, including Horacio Vaggione, Pierre Mariétan, Luc Ferrari, and Éliane Radigue. I moved to West Berlin on a DAAD Fellowship in 1983 and had a great experience there. At that point, I knew I wanted to settle in Europe—my life was here. Paris was the most practical place to settle because I already had many connections. Plus it was a big, noisy city and so I felt right at home. Just a few months after arriving, I also reconnected with a woman who I liked very much. And so we got together, me and my wife Esther. That’s been a wonderful relationship.

This is a generation or so after Alvin Curran and Frederic Rzewski came over to Europe, right? Did you have contact with the composers of Musica Elettronica Viva?

Yes. In fact, I knew Alvin Curran as a student at Yale. And I met Frederic Rzewski after I moved to New York. I was immediately impressed by Rzewski. I remember thinking, “Wow, not only did this guy have the good idea to get a Fulbright and go live in Italy, but now he knows everybody. He’s played for Stockhausen and he’s performed Cage all over. He knows everyone, he’s traveled everywhere, and he speaks four languages! And who is Tom Johnson, compared with a universal musician like Rzewski.” I really wanted to be like him. He was a good model for me. I think it was partly because of him that I dug into my French and German studies a little more, not just in college. I didn’t want to be a dumb monolingual American the rest of my life.

I get a sense of lightheartedness from so much of your work. Your music is marked by simple repetitive structures, often accompanied with narration describing to listeners what they are hearing. The effect for me is usually hilarious. Do you think about humor when you compose?

You can’t try to be funny. As soon as you start trying to be funny, nobody laughs. But if you have a sense of the absurd, and you notice the contradictions, then there are things that will happen that are funny, without trying to be funny.

But certainly some things are funnier than others, right? For instance, in “Narayana’s Cows,” we hear the narrator describe a math problem where cows are exponentially multiplying.

After I see an absurdity like “Narayana’s Cows,” which came out of a 14th-century math book, I know it’s going to be funny. But I don’t think about that. I don’t try to make it funny. I just tell the story. And I know that the absurdity is going to happen, when you have to count the number of cows in each generation and take it seriously.

Do you think about expression as an artist?

No, because that’s subjective.

Yes, but people are feeling regardless of whether you intended it.

Sure, but I don’t aim for expression. I’m not trying to write pretty or Romantic music.

Why not?

Because I want to find the music, not compose it. I look for things in mathematics books, in nature, in numbers. I don’t want to just write something that I dreamed or felt. I don’t want it to be autobiographical.

But isn’t all art autobiographical to some degree?

Yes, but not intentionally. There is something particularly satisfying about music where the logic seems to arise naturally from some discovery outside of myself, where everything comes together without much tampering.

What interests you about mathematical patterns as a way of creating and perceiving your music?

I never believed in music of the spheres. I thought the idea that music came from the galaxies was not convincing.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

You mean, the ancient idea that there is a sort of natural harmony in the universe?

Yes. It’s a nice idea that the music could represent the universe, but I found that the planets are not synchronized in any physical way. Mathematical spheres, on the other hand, they’re out there. They’re as eternal and universal as any other spheres. But you can’t discover them with a telescope or a satellite. You discover them by calculation, by working them out and seeing the symmetries.

So this is a quest for the eternal or universal?

Yes, something like that.

Isn’t it also a way to distance yourself from your materials, as with John Cage’s chance operations?

Well, I’m not sure. But maybe yes. More so, it’s about adding a universal dimension to the material. Of course, sound is material too. But I’m not a sound composer, I’m a note composer. My friend Phill Niblock, now he’s a sound composer. [Niblock died in January—Ed.]

What sort of music were you most drawn to growing up?

I was a classical guy at heart. I played in a dance band as a teenager in Colorado, but I was more of a classical pianist, and I wanted a classical education. That’s why I went to Yale. As soon as I started listening to Webern, I sort of forgot about Bach and Mozart. But not Scarlatti! I even took a course in harpsichord for one semester just because I wanted to play Scarlatti.

Scarlatti is a deep well that never dries up.

You know, the only piece I’ve written directly related to classical music is called “Old Wine New Bottle.” I took three or four fragments from a Scarlatti sonata that I particularly loved and turned them into repetitive music.

Which composers were most important for you in your formative years?

Besides obviously Cage and Feldman, I listened to a lot of Webern and Bartók. Non-western music was also very interesting to me early on. When I was in the army based at Fort Hood, there was a radio program that I listened to every morning about Gagaku—Japanese Court Music. That was a real shock. In graduate school at Yale in 1967, they introduced a course in ethnomusicology for the first time and I was the only person who signed up. It became a private tutorial where I listened to a lot of great recordings and learned a lot about Gamelan.

Do you still play the piano?

Yes, I like to sing and play, in particular Southern Harmony and Sacred Harp Music. I sing hymns at the piano almost every night. That’s my prayer time. I don’t actually pray very much, but I sing a lot, and memorize the texts.

What do you think about some of Europe’s most highly regarded composers of the last 50 years? Do you like the music of György Ligeti, for instance?

No, it’s too complex. I don’t like important music.

What makes Ligeti’s music too important?

It’s the same with the music of Pascal Dusapin. There’s too many instruments and it’s too long.

Well, in comparison to your work, I guess that would describe a lot of music.

Yeah. [Laughs.] I was just listening to the symphonies of Alfred Schnittke and I thought, ”This is too important, too pretentious.” There’s more instruments than necessary, more time than necessary, more ideas than necessary.

Where do you think this comes from? Is it a sort of musical Protestantism?

Yeah, maybe? It’s a gift to be simple. I like modest people who don’t pretend to be important and wear fancy costumes. I think it’s partly just human nature. I don’t like people who are too flashy, too important, who want to be the leader, to attract attention, to try to sell me something.

How would you like the world to remember Tom Johnson?

I just want people to come away with a few notes and maybe a desire to play or listen to some of my pieces—for the ideas to circulate. I’m not trying to change the world. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.