In 2022, I sang Benjamin Britten’s “War Requiem” at the Royal Albert Hall. During the performance a spotlit figure caught my eye, moving his hands dynamically and expressively with the musical flow, but who was neither a conductor, nor a singer, nor an instrumentalist. That figure was Paul Whittaker: a Deaf musician who uses British Sign Language to interpret musical works with major choirs and orchestras.

On the same day I interviewed Whittaker, the Los Angeles Philharmonic and Gustavo Dudamel performed Beethoven’s “Fidelio” at the Barbican in a staging co-created with Deaf West Theatre. Their artists signed the dialogue scenes intercutting the music, and doubled the singers’ roles; the Financial Times’s review described “a sense that another dimension had opened up, giving a deeper appreciation of Beethoven’s embrace of humanity in the opera.” It’s a sign that the classical music world is starting to address itself to the experiences and imaginations of the Deaf community. Deafness is part of musical history: Beethoven is the most obvious instance, but Vaughan Williams, Smetana and Fauré also experienced hearing loss.

Whittaker’s work has implications for hearing and d/Deaf audiences alike. The Deaf community has a complex and multifaceted relationship to music, as Whittaker explained to me. While there are of course many notable d/Deaf musicians, he noted that some Deaf people—often from the older generation—feel that the art form is not for them.

Such resistance has its roots in the historical exclusion of BSL. It was only officially recognized as a minority language in the UK in 2002, and given legal protections in 2022. Teaching BSL to Deaf children was banned until the 1970s. Its opponents insisted that “oralism”—speech in combination with lip reading—was the only way they could learn to communicate. Music, as a hearing-centric art form, was caught in this cultural crossfire. Currently, Music and the Deaf, founded by Whittaker in 1988, is the only UK charity exploring the enriching role music can play in the lives of people experiencing different levels of hearing loss.

Whittaker’s schedule is comparable to that of a top international soloist. When we spoke over Zoom, with his BSL interpreter Stephen, he had just returned from Malmö, where he’d been creating a version of Ravel’s “Ma mère l’Oye” accessible to the d/Deaf community, and then traveled to the Isle of Skye, via a Sunday concert at Wigmore Hall in London, for a series of workshops with the National Youth Choir, creating games and activities using the Kodály method. Next stop? Ludwigsburg, to work with the Mahler Chamber Orchestra.

VAN: What do you want to achieve when you’re onstage?

Paul Whittaker: I want to convey my love and understanding of that piece of music to the audience in any way I can. Obviously, some people will be able to hear the music, and some will be able to see the performers. Hopefully what I do adds to that in some way. When I do signed concerts, there are quite a lot of hearing people who will say to me—even though they do not understand BSL or aren’t experts on music—that what I do adds greatly to their enjoyment of the piece. So it’s not just about making it accessible to Deaf people. It’s about making it as entertaining and informative [as possible] to absolutely anybody.

So many people still think that music is very much about what you hear. And it’s not—you use all your other senses. My work is about trying to make people aware that music is much, much more than what goes in your ear.

What kinds of musical details do you show when you interpret a piece?

It’s really important to show the emotions. There are certain technical things you have to show: for instance, in a fugue, if a theme is turned upside down, or if it is done at half speed or double speed, you can put those details in.

Sometimes you might be pointing over to the orchestra, guiding people to look at a singer who is about to perform, or a percussionist—there’s something over there—so they can relate the physicality of the singer or instrumentalist to what I’m signing. It’s a holistic approach.

The hardest period of music to interpret [pieces from] is the Classical, because of its form, and the relationship between keys. You cannot show that this first subject is in E-flat and then it concludes in B-flat. Perhaps you could show they have different levels: E-flat here, B-flat there [Whittaker gestures with his hands at different heights], maybe G minor somewhere over here. But it’s much more complicated than a square.

How do you prepare? What is your process, whether for instrumental or choral works?

With any piece of music, I start by sitting down with the score. I mark out the major themes; if there’s a narrative behind it, I’ll think about that. I’ll mark up any major musical landmarks. With a choral or vocal piece, it’s far, far easier. It’s always helpful to have a literal translation [of the text]. It gives me the freedom to create a signed narrative and match that to the music.

It’s important to realize that BSL is not English. It doesn’t follow the same word order and has its own grammar and syntax. When you’re signing a piece of music you have to be aware of those rules, but you also have to break them.

It’s very important that what you do matches what’s happening onstage. It’s not the same as most “interpreter” jobs where you hear something, process it, and give it out again three seconds later… It’s incredibly frustrating watching someone signing a song or piece of music when it doesn’t follow the beat or pulse. Ach!

You know that the players and conductor have worked together to create an interpretation. It’s almost as if I’m a reverse conductor. I watch the conductor, I feel, read, and am aware of the overall character of the performance, and then I convey it back to the audience. It’s a cyclic thing.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

Does the art of choreography influence what you do? Do you think of your work as theatrical in that way?

I wouldn’t say that there are any choreographers that influence me. But years ago, when I worked with Rambert Dance Company, I was fascinated by what they were doing and how that choreography linked or—quite often with contemporary dance—didn’t link with the score. One of the challenges with [signing] dance is that the musicians are invisible. Something I’ve tried to avoid when I’m signing is to go, There’s a flute, there’s a violin, there’s a trombone. Because that supposes that a [d/Deaf] audience member knows what those sound like.

I remember doing one piece with [dancer and choreographer] Siobhan Davies. We were chatting on one occasion about sign language and the rhythm inherent in that, and the physicality and rhythmic sense of the dancers. I got the feeling that she—and a couple of other choreographers—were fascinated in exploring this relationship. I was always fascinated by how dancers could perhaps convey more of the musical detail, rather than just choreographed movement.

When we first spoke over email you told me that the Britten “War Requiem” was one of your bucket list pieces. What are the others?

The number one piece on my bucket list is James Macmillan’s “Seven Last Words from the Cross.” I’d like to do Haydn’s “Creation”: There’s a lot of humor in it—Haydn is a fun guy!—you’ve got insects buzzing and so on. It’s just an antidote to the heaviness of, say, Rachmaninoff’s “The Bells.”

Another piece I’d love to do is Schoenberg’s “A Survivor from Warsaw,” which hardly anybody does. I’d love to have a go at that, particularly because of the sprechstimme—having to reflect that half-spoken, half-sung quality in my delivery.

Are things improving in the classical music world’s efforts to encourage access for the Deaf community?

There is a lot of work to be done. Overall it is still pretty poor. I know that quite a lot of orchestras do school and family concerts. What irritates me is that the organizations will provide an interpreter for these concerts, but they will not provide access for anything else in their season. They dangle a carrot and then take it away again! I’m sorry: You’ve already got someone into the hall, but then you’ve brought this barrier down because you’re not providing any more access.

I’m trying to get all these organizations to move beyond just having an interpreter at a concert. You need to have some kind of pre-concert talk of interest to everyone, not just Deaf people; to organize some kind of workshop where they can meet the musicians, wander around the stage, try the instruments. That kind of background is so important. Sometimes you need a different level of engagement: what an opera actually is, what a cantata is as opposed to an oratorio, that level of education.

It sounds to me like a similar situation to broader problems with classical music education: There isn’t the same bedrock of knowledge or active engagement that comes from early education and school that helps people through the door. Do you agree?

Yes. It is. The BBC Proms, I think, are incredibly tokenistic. They do a family concert, a relaxed concert, but they don’t think of [providing an interpreter for] a big choral concert. There is a performance of “Messiah” this summer, with a whole load of choirs from different communities. Now, something like that is perfect. But they don’t think about that and offer only a CBeebies concert or a relaxed concert. It’s not encouraging or providing access to this massive range of classical music.

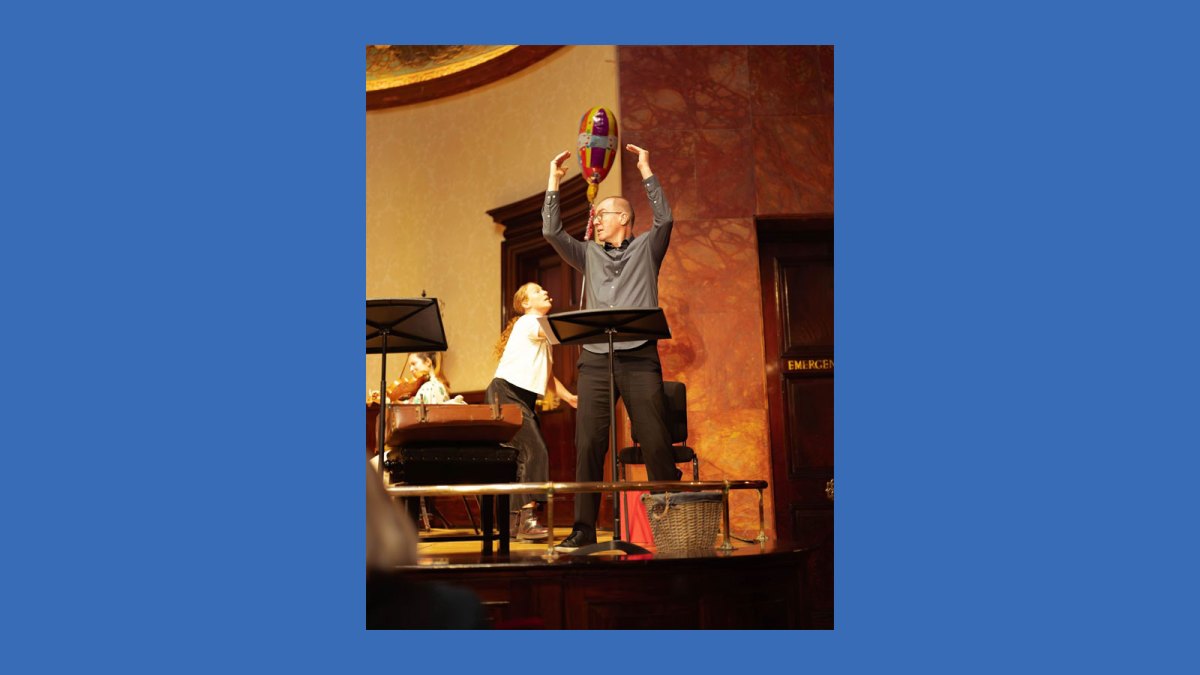

I don’t know if you’ve heard of Children’s Classic Concerts, based in Scotland. They put on fantastic concerts for young people which sell out the Usher Hall and the Royal Concert Hall in Glasgow. They are as far away as you can imagine from the way that most school concerts are put on, where a narrator says, Aaron Copland wrote this piece of music and it is about this, and then they play a bit. These concerts, which are done with the Royal Scottish National Orchestra, have a theme and they create a script. It is highly interactive: there are visuals, games, all sorts of stuff. It’s fabulous, I love working with them. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.