I. “You Want to Stop Listening”

1996, Bregenz Festival.

The semi-staged world premiere of my opera “Nacht” on texts by Friedrich Hölderlin. The journalist Reinhard Kager predicted that the work would have a great future.

Looking back, I understand why. Thanks to the spare scenic means (different plot strands were illuminated using different kinds of light—as intended!—and the through-composed choreography of the instrumentalists was realized), the work was able to unfold, its dramatic power unhindered. The German music critic Heinz-Klaus Metzger was in the audience and wrote an extremely positive review in Die Zeit. For the first time, a broader group—of those interested in culture—was made aware of my music.

I will always be grateful to the Bregenz Festival and Alfred Wopmann, who was artistic director of the festival at the time, because that commission and successful semi-staged performance changed my life.

But Reinhard Kager was wrong.

Two years after the premiere, the first fully staged performance of “Nacht” took place at the same festival. In it, the director steamrollered the drama I had composed and, in the resulting wasteland, planted something new and meager. At the beginning, an underaged girl lounged about, and towards the end, nine boys fell dead in a row. If there was a connection to my opera, I couldn’t find it. But the director was clearly enjoying himself. In the middle there was listless shouting, suffering, perpetration of violence; no one could figure out what was happening, but it was all very, very modern. The character of Susette Gontard was squeezed into a robe that looked like a condom, while Empedocles was represented by a fading vacation photo of a country road in Greece, and so on. One “brilliant” directorial idea followed the other, with my operatic composition a more or less fitting soundtrack.

Although the musical realization of the piece was outstanding, the production was nothing more than a critical success. The Bregenz Festival was praised for its courage in doing something so risky and new. If Heinz-Klaus Metzger had seen that performance, instead of the semi-staged one, his verdict would have been significantly less positive.

After a staging in Frankfurt that was even more horrible, and a laborious resuscitation in Lucerne, the opera disappeared.

2024, Bern Theater.

The world premiere of the second part of my operatic diptych on toxic masculinity: a co-commission from the Bern Theater and the Ernst von Siemens Music Foundation.

“Liebesgesang” (“Love Song”), for one woman and one man on stage. No orchestra, not a single musical instrument.

An opera without musical instruments is an unusual thing.

A challenge.

I love challenges like that.

When I compose for, say, 50 pianos, I’m fascinated by questions like: How should the instruments be tuned? How should they be arranged in the space? And, especially, how can such a performance be conducted? Simply writing a traditional score with 50 pianos in it would be rank dilettantism.

When I compose for darkness, I’m fascinated by the question of what darkness means for the people performing. How will they communicate with each other? What freedoms do they need? What qualities result from this unusual situation and only from this unusual situation? Simply writing a traditional score, saying that the whole thing is to be memorized, and turning off the lights: that would be rank dilettantism.

Just the music of two people—nothing else. To compose for two voices and act like it’s business as usual would be rank dilettantism:

- When there’s no orchestra, there’s no such thing as an entrance at the wrong pitch. Melodies can be sung higher or lower; the tempi can be flexible if necessary; and SHE and HE—the two characters in the piece—can follow the musical expression autonomously. That creates an unusual freedom that should be explored.

- Without instruments, the sounds from the stage become the only musical accompaniment.

- The visual rhythm of the staging gains a structural meaning.

- Because there’s no orchestra that could overwhelm the singers, the comprehensibility of the language rises exponentially.

- …

The result was a rich palette of artistic possibilities that I used consistently in my work.

On May 31, 2024, I attended the so-called world premiere of “Liebesgesang.” Misguidedly, I assumed I was prepared for the worst. A few days earlier, I had been asked to agree to numerous cuts. Apparently the vocalists were overwhelmed because the piece was too demanding. Also apparently, the director had found an elegant solution with these cuts. I had been ignored for months; now it was too late for a discussion. I had no choice but to agree, which I did under protest. Unfortunately, I’m familiar with such situations. I’d been warned.

Even before the opera began I could tell why the singers were overwhelmed: The director had placed them in the (modified) orchestra pit, surrounded by the audience on all sides. The poor things had to sing and speak into the empty space around them for an hour and a half.

And then…

My scenic instructions were followed only rudimentarily. Some were completely ignored (like the instructions concerning the sounds from the stage). Others were realized with an obviously tongue-in-cheek “literalness.” (Two examples. One: In the score, it says, “Optical signal with a precisely identifiable beginning / perceptible for the audience as well / Length of the signal indeterminate.” This was done with flickering monitors and looked like a random technical disruption. It began at the right time, but was then composed into a separate, stochastic light rhythm. Two: In the score, it says, “SHE exits the stage, goes slowly through the audience to the entrance of the hall.” In the staging, SHE climbed up a ladder to the gallery of the theater and had to push aside the people sitting there.)

My artistic statement was turned upside down. Instead of toxic masculinity, the opera was now about a “thoroughly normal” broken relationship. The man’s emotional abuse was trivialized and the woman was shown as hysterical.

Watching and listening to the singers, you could tell they took no musical pleasure in the work. The sonic beauty of the sustained intervals was unable to unfold—a problem that started with the acoustic situation—and the melodies were unable to fulfill their expressive potential. Passages that could have been realized freely and sensually sounded strict and stiff.

The director clearly wanted to make the two singers suffer from my score the same way the two characters suffered from their relationship.

Where cuts weren’t enough to invert the meaning of my opera, they violently modified the musical text. In the libretto, HE has the line “In der Scheide will ich sein” (“I want to be in the slit”), a phrase that is repeated many times. In my opera, SHE takes the initiative (singing an abstract vowel and sounding like a musical instrument). SHE leads, HE follows her in unison, up into his falsetto, until SHE sings so high that HE can’t follow anymore; SHE leisurely, pleasurably returns to her low range, and HE can sing his line in unison with her again; the whole thing repeats, differently… The score leaves plenty of space for this loving game: at least two and a half minutes in total, up to around five and a half minutes. That section was radically condensed and carelessly drilled down; I’d guess that it lasted less than a minute. Instead, the director composed a new measure of his own, in which HE bellows, “In der Scheide will ich sein.”

The performance was a great success.

There was widespread admiration for the clarity with which the director brought the horror of this relationship to the stage. The Bern newspaper Der Bund headlined a section of its review with the bold text “Man möchte weghören” (“You want to stop listening”), and praised the composer for writing music as cruel as the relationship the director showed on stage.

“You want to stop listening”—that is the most negative thing that has ever been said about my music.

“You want to stop listening”—that is opera declaring bankruptcy.

But the director was good.

Very good.

Excellent.

The worst part is, all of this is normal in the field. When I refused to play the part of the beaming composer, when I avoided the premiere party, when I didn’t feign enthusiasm to the singers, I was accused of unprofessional behavior.

The problem is systemic. For 43 years, I’ve been experiencing essentially the same thing.

Of the many experiences I’ve had, two things that were said to me stick out. One was charming; the other, brutal.

- The 2013 world premiere of “Thomas” in Schwetzingen, Germany. One of the scenes includes a highly unusual expression of erotic love for the human body, full of pain and loss. In rehearsals, it turned out that the director wanted to recast this scene as situation comedy (!). The librettist and I went to ask for a correction and received the answer: “If I do what you want, where am I?” (In my recollection, no one laughed during the performance, but everyone was prevented from having an intense artistic experience.)

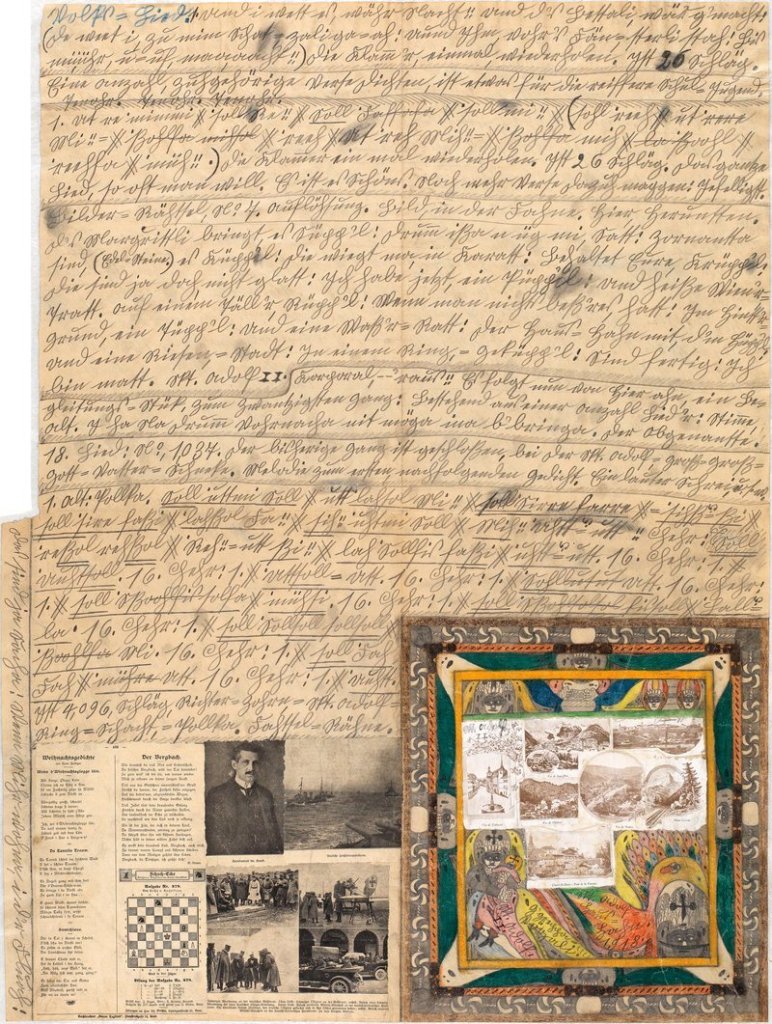

- “Adolf Wölfli,” 1981 in Graz, Austria. Composer to director (desperate): “You’re destroying my opera!” Director to composer (mocking): “A good opera cannot be destroyed.” (That sentence resounds in my head when I take in the applause after a catastrophic staging—completed by the sad thought: “You have no idea what you were prevented from seeing.”)

Those two quotes summarize the aesthetic ethos of (central) European regietheater: Realizing on stage what is intrinsic to the work requires the director to renounce their authentic self and must never happen. And: Any violence toward the work is legitimate. If that destroys it, the work was already weak.

What is opera? This is my definition:

Opera = Theater of Emotions.

The emotions are conveyed through the music (voices and instruments), based on the conditions evoked in the libretto (traditionally: the plot) and its text.

In most stagings of my operas, the emotions I composed were either partially or completely prevented from being realized due to a counterproductive staging. Still, there was always something left (since, as we’ve learned, a good opera cannot be destroyed), and I was “successful” as an opera composer. But what might have been possible? No one knows that except me.

I can count the stagings of my operas that allowed the emotions in them to take on the life they deserved on the fingers of one hand:

- “Melancholia” with Stanislas Nordey at the Opéra Garnier in Paris, 2018

- “Morgen und Abend” with Graham Vick at the Royal Opera House in London, 2015

- “KOMA” with Immo Karaman at the Stadttheater Klagenfurt, 2018

- “Morgen und Abend” with Immo Karaman at Oper Graz, 2022

- “Sycorax” (the first part of my diptych on toxic masculinity) with Giulia Giammona at Bern Theater, 2022

II. Libretti

The cliché of the opera with good music and bad text has come and gone. Today, there can be no doubt that the high art of libretto writing has always been essential to the creation of arresting opera.

But what the music does with this material is the decisive factor. The best libretto is worthless if the music composed to it isn’t good enough. The reverse is true as well: Richard Wagner’s libretti demonstrate that musical-dramatic power can compensate for blatant weaknesses in the text.

Things get especially interesting when the composition is able to interpret the libretto in an unusual way, or even subvert its meaning.

The nobleman Don Giovanni toasts with the lascivious words, “Viva la libertà!” But Mozart didn’t set the words as the censors would have expected. Instead, he interpreted the phrase as a sort of military call. Then he combined three simultaneous dances to represent three different social classes.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

Or take the line “Mann und Weib, und Weib und Mann, / reichen an die Gottheit an” (“Man and wife, and wife and man, / attain divinity”) from “Die Zauberflöte.” Mozart could have set the text in the same unctuous style as Sarastro’s aria “O Isis und Osiris.” Instead, he decided to illustrate their union with just a few sensual notes, glorifying the metaphysical aspect of love. Then, he added ecstatic soprano lines on top that were likely perceived as stylized, ecstatic cries of pleasure: a pleasure that arises because of—not despite—the fact that Pamina and Papageno are from completely different social classes. Later, in the spot where (based on the libretto) you would expect the climax of the opera to be—during the trials of water and fire—Mozart makes it obvious that he’s not interested in the royal couple at all.

Beethoven, “Fidelio,” Act II., Scene 1. A saccharine text:

I see how an angel fragrant like a rose

Comforting stands by my side,

An angel, Leonora, my wife so alike

To lead me to freedom, to the kingdom of God.

Beethoven turns the passage into an ode to freedom, to deliverance. He doesn’t change a word. But if you read the text and try to forget all its associations with Beethoven’s music, you’ll recognize how radically the composer reinterpreted this simple verse. That’s how opera composition works.

Sung text is difficult to understand. Usually, only single words or clauses are identifiable. The rest has to be filled in—traditionally, with help from the staging.

The current practice is completely different. Usually, a director will look for a new aspect in the content of the work (meaning the libretto) and stage that, in fundamental contrast to the content of the composition. The fascinating relationships that can result from these contradictions require the text to be precisely understood, meaning the staging is directed to the minority of the audience—such as critics—that can imagine the text based on the music.

It’s true that many years ago, stagings were an essential way of introducing new facets to opera. There was a famous (and probably apocryphal) exchange between Karl Böhm and Walter Felsenstein during the rehearsal of a Mozart opera at the Salzburg Festival. “Tell me, esteemed colleague,” Böhm supposedly asked, “what are you staging up there? Strindberg?”

“I guess I have to,” Felsenstein replied, “if you’re conducting Lortzing down there.”

That was a long time ago.

Walter Felstenstein died 49 years ago, Karl Böhm died 43 years ago.

Today, what is the point of presenting the 114th radical new take on “Le nozze di Figaro” by directorial genius X—a take even more radical than the 113th one presented shortly before by directorial talent Y or up-and-coming star Z?

Is that really what we need? Isn’t it much more important to take audiences on a journey through the beauty, intensity, and abysses of Mozart’s music? To make the humanist aspects of opera viscerally and emotionally palpable? To combine and contrast 21st-century lighting technologies with the fascination of an unamplified human voice and a live symphony orchestra, all at the highest artistic level?

The decades-long tradition of concentrating on works from the past, then focusing on the libretto instead of on the music, has changed the profile of an opera director. Deeper musical knowledge is no longer expected. It’s more than enough to be able to read music and follow the piano reduction as the CD plays.

I’ll never forget a Zoom conversation I had with a director. It wasn’t a dialogue, but a magnanimous gesture from an all-powerful authority who was informing me of all the things that were going to happen to my opera. She spoke only about the text. After what felt like a half-hour monologue, I asked her what role the music played in her concept. The answer was, “Of course I’m only familiar with the recording, and I have listened to it.” A pause. When I asked her if she was familiar with my music beyond that recording, she said she was not.

She clearly enjoyed that recording, since she stuffed the chamber orchestra in a closed wooden box and had the music piped to the audience through loudspeakers. The subtle differences in sound (for example, between harpsichord, harp, mandoline and zither) were conveyed to the audience electronically. One critic was reminded of Krautrock. Still, the performance was a great success (see above).

There’s a simple reason why directors prefer to work only with the text. They can read the libretto easily. They can read the music only with difficulty. And they can’t read contemporary scores at all.

Once it was expressed to me this way: “There are situations in which the director must protect the libretto from the composition.” This was in total seriousness.

Therefore: If the music expresses something different than the original intent of the libretto, then the staging must express something other than what the composition would require. Because obviously opera is about text, not music. (Irony off.)

Painful experiences in the past have taught me that the above claim is quite true, with a slight modification: “There are situations in which the director, having made incorrect decisions while reading the libretto and in ignorance of the music, has no choice but to cling to those decisions as he originally conceived them.”

By the way, a librettist who gets involved with the staging of his opera and “corrects” the intentions of the composer has committed premeditated vandalism.

III. Artistic Freedom and Artistic Competence

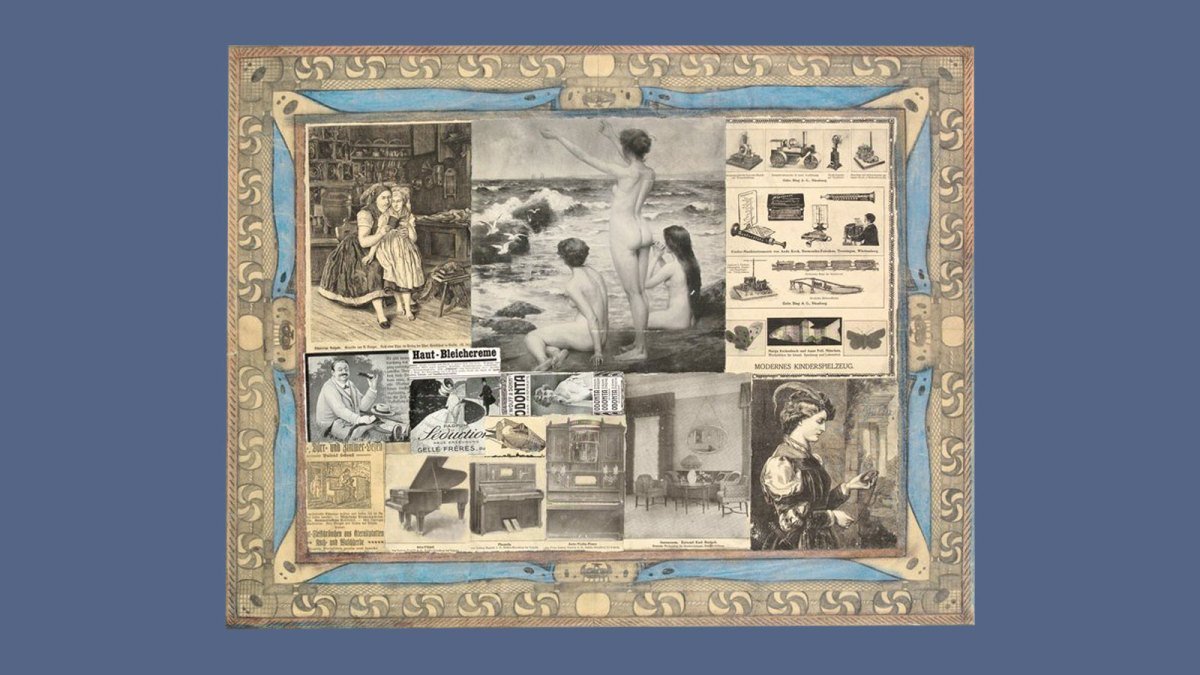

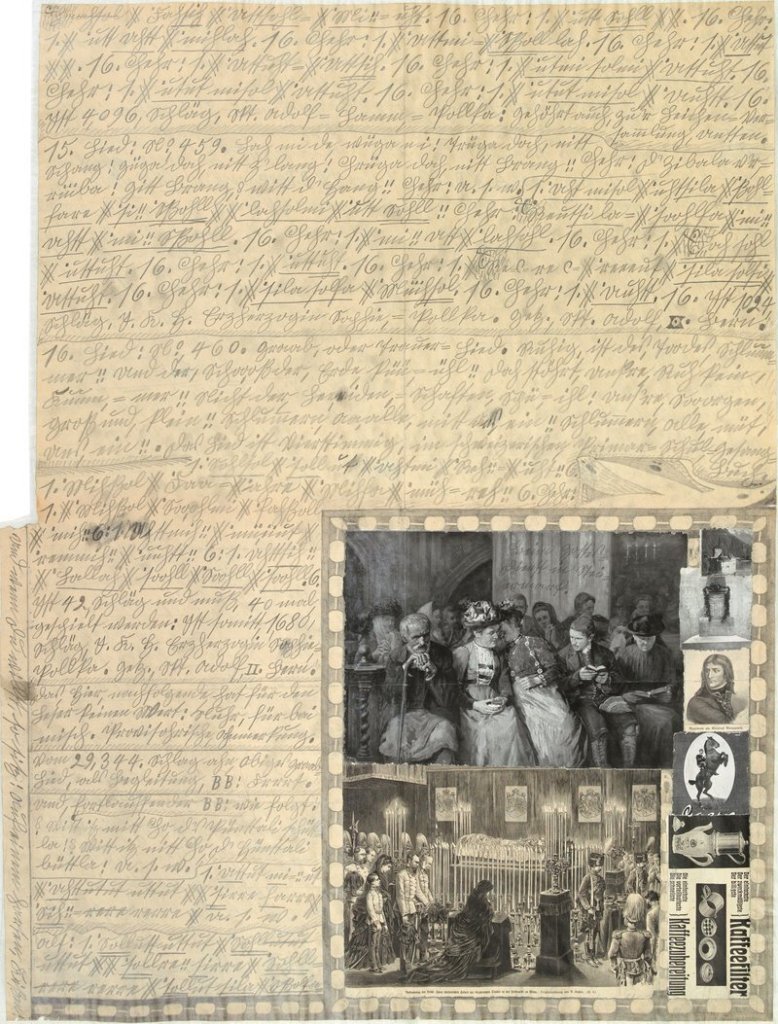

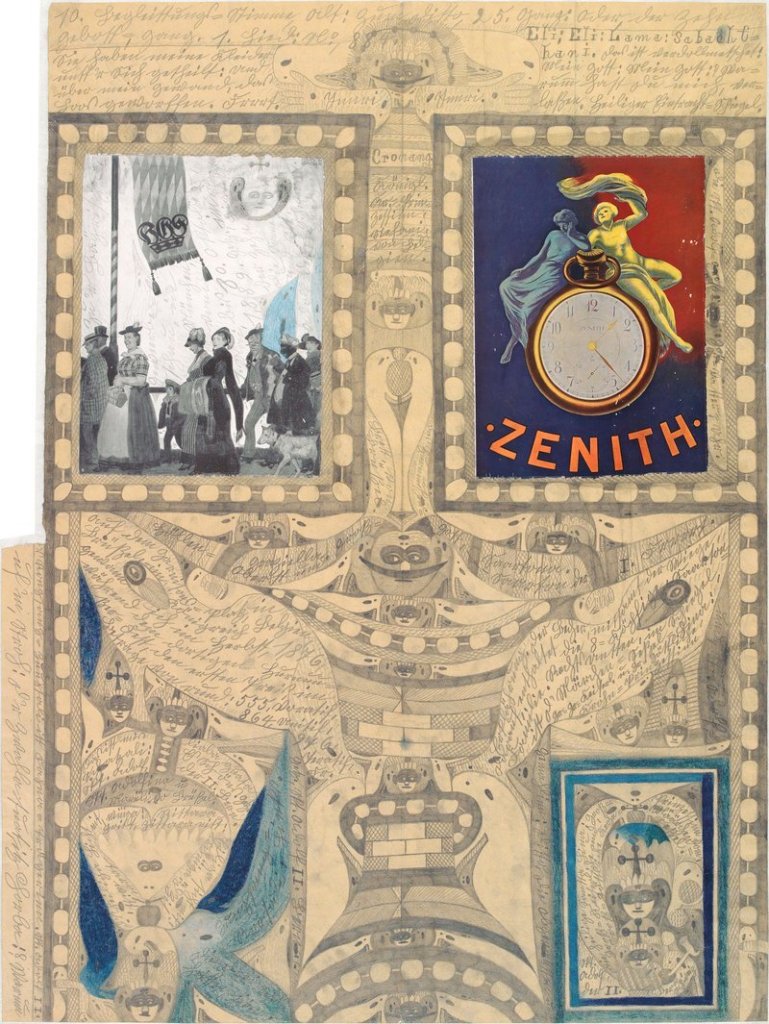

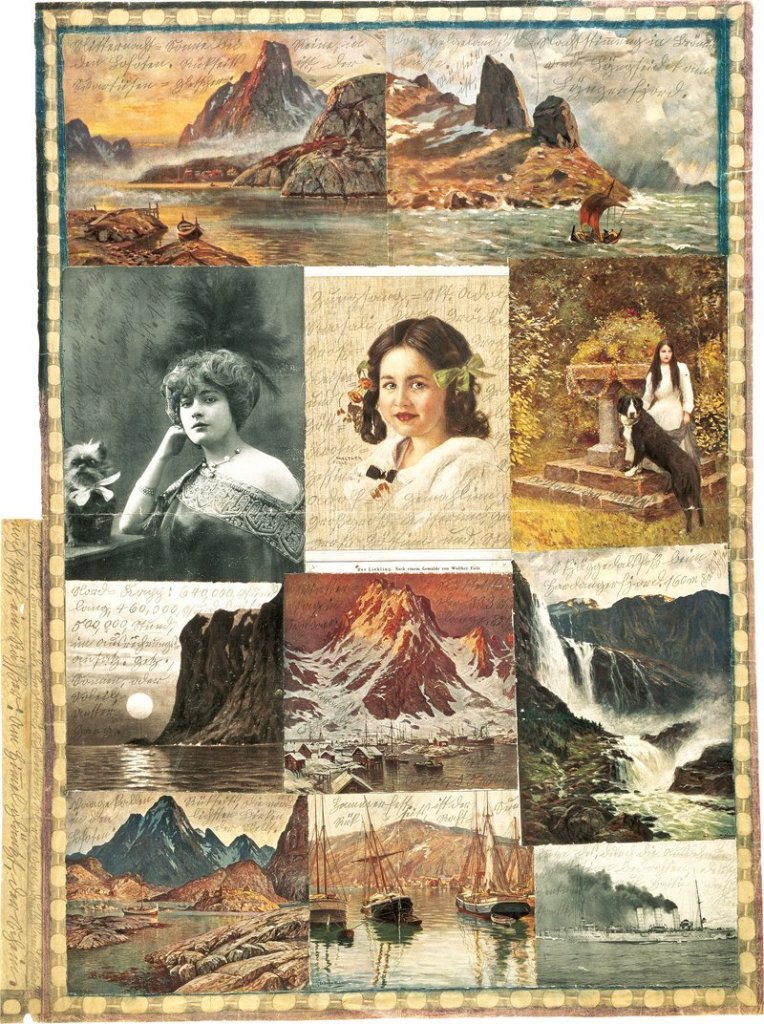

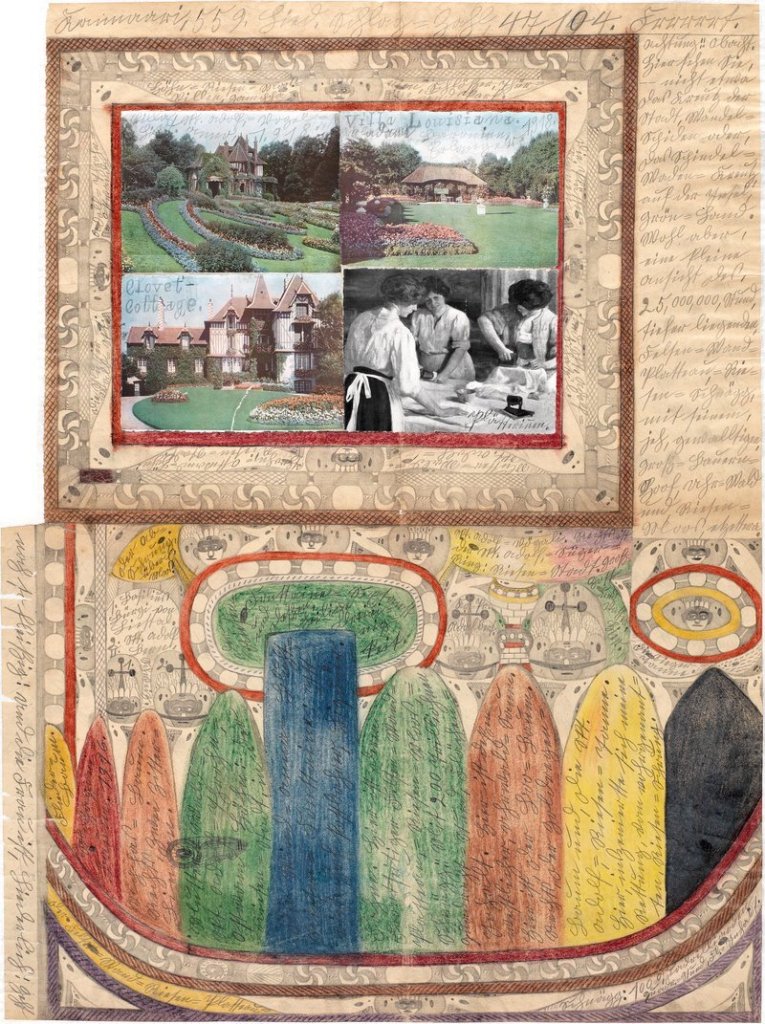

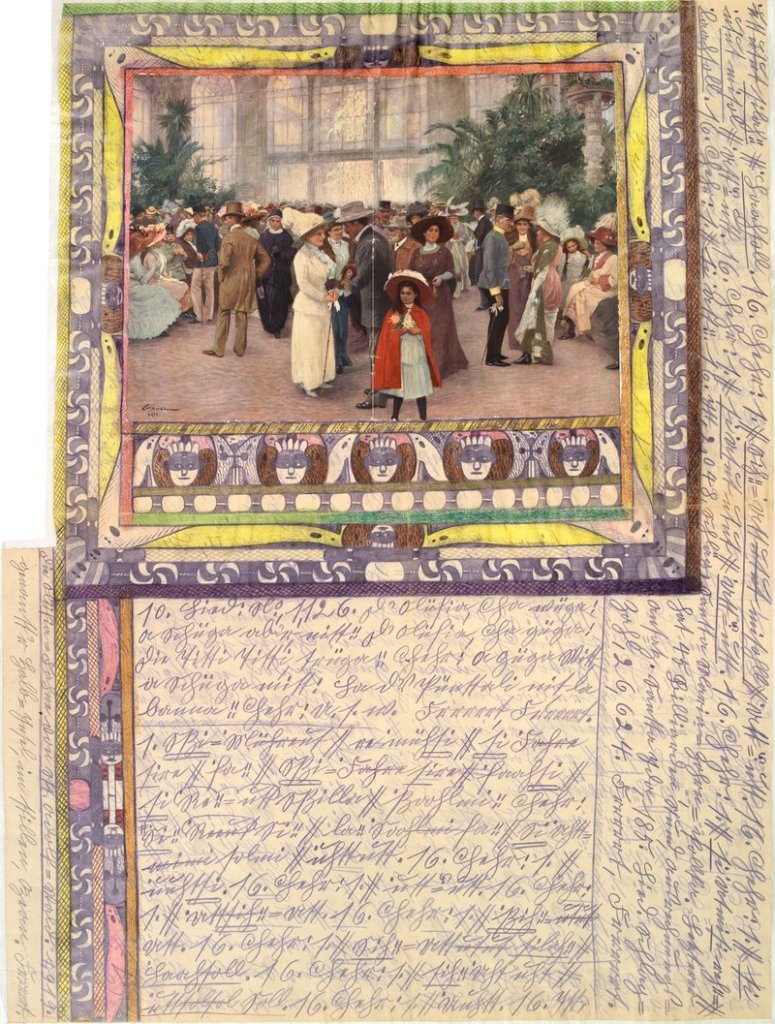

In 1981, I received my first opera commission, for a roughly 20 work minute work on texts by the Swiss artist Adolf Wölfli. Naturally I began studying his writings and drawings intensively. It was as if I could feel a terribly traumatized personality screaming back at me from the works, full of guilt and consumed by the failure of his redemption fantasies.

Completely disregarding aesthetic norms, Wölfli took whatever he found—from folk songs to travel reports and various newspaper clippings (mostly advertisements)—weighed it up, and deemed it all too slight to balance out the catastrophe of his life. It became clear to me that the academic new music I had composed until that point could not do justice to the material. I remembered something my teacher Iván Eröd told me that I’d never wanted to believe: “Opera is always eclectic.” And I understood that I would need to adapt that sentence for myself in a way that was consistent with my artistic conscience.

It wasn’t easy. Admittedly, in “Adolf Wölfli,” I never really achieved it. My second opera, on a wonderful text by Ilse Aichinger, “Nicht vor Mailand,” was also a failure. In the 1990s, it was scheduled for a concertante performance at the Salzburg Festival—to this day, I have no idea why. But after a long internal battle I called Andrea Seebohm, then the manager of the Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra, and asked her not to perform the piece. I told her it wasn’t good enough.

It wasn’t until my third opera, “Nacht,” that I was satisfied.

I could have made this process easier for myself by sticking to what I knew. To the media, I would have emphasized my uncompromising loyalty to my own language—that would have met with an exceptionally positive reception. And the director would have been satisfied with a low-maintenance soundtrack.

But since then I have nothing but contempt for the “geniuses” of the opera industry who retain an “uncompromising loyalty to their own language,” whether that “loyalty” makes itself felt in the composition, in the staging, in the set design or in the costumes.

When I’ve tried to explain to directors a statement in my music, the effect of a certain passage, and how those clash with a certain scenic decision, then I’ve usually been accused of inappropriate meddling in the director’s sphere of control. Many of my colleagues have described the same thing happening to them.

In general, I can say that I’ve rarely been confronted with the accusation of an “exertion of power” in aesthetic discussions, and when it has happened, it’s exclusively been in the context of opera stagings.

For me as a composer it’s never about “exertion of power.” It’s only about creating art that is capable of moving people with the necessary means.

Directors are in a difficult position: They are used to dealing with works from the past whose dramaturgies are hopelessly old-fashioned and whose content is problematic. They’ve learned that they are allowed to do whatever it takes, that they must do whatever it takes, with one exception: allowing the preexisting aspects of the work to unfold. And then you get a few obnoxious contemporary composers coming in and expecting their music dramas to be presented on stage as they were thought, heard, and lived through in the imagination! Quite reasonably, most directors feel like they only have one choice: to flatten the work with the full force of their theatrical violence.

Whenever the guest composers who come to Columbia University present their operas, I ask them about their experiences with (central) European directing teams. The answers are always the same: that the meaning of their works was turned upside down. I’ll never forget the agonized expression on Kaija Saariaho’s face as she described, in her gentle way, that the director’s staging said something completely different than what she had composed.

In 1997, during the applause for the premiere of György Ligeti’s opera “Le Grand Macabre” at the Salzburg Festival, the composer grabbed one of the prop guns lying around and aimed it at the director. There was no public discussion about why Ligeti did that. No one cared. At most, people were amused that the composer made such an inappropriate gesture—he should have been grateful that his work was given the honor of being performed at such an important place…

I don’t know what it was that upset Saariaho and Ligeti so much. But based on my own experiences, I can imagine the extent of the damage to their works. Out of a surfeit of difficult experiences, I’ll describe two more especially painful ones:

“Nacht,” in Frankfurt (2005). After about 20 minutes, the orchestra goes silent. Two voices —soprano and baritone—sing a quiet, hopeless love song in parallel intervals. But, in contrast to the text and music, the director had the idea of making a third person the central character of the staging, who would “complete” this intimate scene by stamping around loudly. Later, according to the score, four Hölderlins are supposed to walk around the audience reciting the text “Ich will kein Jakobiner sein” (“I don’t want to be a Jacobin”), first screaming, then getting softer until they finally whisper, in a precisely notated choreography. But the director put them underneath (!) the rows of seats, so that not only was the spatial aspect of the passage lost, but the volume and luminosity of the vocal sounds were drastically reduced. The power I composed into the passage was gone.

“Bluthaus,” in Munich (2022). Immediately before and after the opera, vocal music by Monteverdi was performed. The transitions were brutal. They damaged the effect both of the “overture” (it was without instruments and just for a male and a female voice, but because of the choral music, you couldn’t tell how unusual this opening was), and the conclusion (a tonal chord with an unresolved dissonance, appearing suddenly and remaining there monolithically; the consonances and dissonances of Monteverdi’s music that were introduced afterward canceled out the emotional statement of my conclusion). I didn’t understand the staging during these sections. When I asked about it, I was told that it was a reference to the TV series “Tatort,” a Sunday evening police show popular in Germany that is largely unfamiliar to me.

Musically, the performance was magnificent. Still: the main character, Nadja, who is the victim of abuse by her father, left me oddly cold. Yes, the vocalist had prepared the part perfectly, had sung it with confidence and beauty of sound, and had to interpret Monteverdi on top of that. (The magazine Opernwelt named her Singer of the Year with good reason.) But Sarah Wegener had performed the same role with noticeably more humanity and warmth at the premiere in Schwetzingen; her interpretation had been more poignant, more moving. With the (as I said, excellent) singer in Munich, it seemed to me as if she had put up a wall between her emotions and the audience. It wasn’t until a few days later, when I read the reviews, that I understood what had happened. The “Tatort” reference was meant to imply that Nadja had murdered her parents.

That went further than I could possibly have imagined. In “Bluthaus,” I was reckoning with my own past: Nadja was abused, I was abused. In the last section of the opera, Nadja gathers all the objects associated with her memories, locks up her parents in a suitcase or in a closet, destroys everything that made the apartment habitable, and confronts the horrible truth. It’s the only way she can overcome her traumatic experiences. By reversing the victim-perpetrator dynamic, the director reduced this existential statement to a cheap thriller, and mocked the suffering of the abused.

Nadja is a character who develops from a state of repression to clarity, who allows herself to feel pain and grows stronger in the process. The epigraph for my opera could be Ingeborg Bachmann’s phrase, “Die Wahrheit ist dem Menschen zumutbar”: People are up to the truth.

But not in this staging.

Nothing—nothing at all—justified this reversal of the victim-perpetrator roles in the work. The director had to add Monteverdi’s music to give themselves the space to make this substantial intervention in the composition. A shame, a real shame: The opera’s vision of a victim surviving abuse was turned into banal revenge fantasy.

Directorial high-handedness is everywhere in the opera world. Many of my students have had to face it too. From a surfeit of stories, I’ll choose one especially extreme case. This student had composed a soft, intimate homoerotic scene. The director destroyed the scene with loud onstage noises because, (according to the “reasoning”), sex between men always has an element of violence.

It is common practice in opera—though thank God there are exceptions—for directors to overwrite and reinterpret music theater compositions. The question has become increasingly clear: Why?

Why, in all these years, has a director never asked me to sit down and go through the score together, before they begin developing their concept? Why, in all these years, have I been so rarely asked any questions about the composition? Why, if I have attended rehearsals, have I generally been treated as an intruder, as someone disturbing the director’s work? And for the times I wasn’t there, why was I often not contacted until the planned vandalism of my opera was so advanced that the staging had the potential to violate the work’s copyright, and therefore my permission was needed—usually just before the premiere?

Sure, one could argue that the music is simply the soundtrack for the staging. You wouldn’t argue about the staging with the people who supply the theater light bulbs. But that still begs the question: Why is music in the practice of music theater reduced to a mere soundtrack?

Here’s my attempt at an explanation:

When I recall how hard it was for me to enter the field of opera, how difficult it was—and still is—to live up to the material (in my case, the libretti or text the libretti were based on) in an artistically responsible way, I can understand that the effort is too great for many directors. And that due to personal laziness or technical inability these directors, claiming artistic freedom, take the music (in the best case) as the initial spark for yet another demonstration of their personal style.

Making sure the singers’ movements and actions fulfill the precise temporal requirements marked in the score; evoking the emotions composed through the relationship between music and text; staging highly effective dramatic scenes: all that is a big challenge, a three-body problem that most directors are unable to solve. So they cut the second “body” (leaving out the part where they would have to evoke the composed emotions and instead just staging their own interpretation) and end up with a “two-body problem.” Which is, of course, mathematically trivial.

It seems as if there is an unspoken agreement not to allow composers to act as the owners of their own works. The high-hanging fruit of an adequate staging of the piece is written off as sour grapes. It is denounced as “doubling” or even as “Micky Mousing.” That makes life easy.

The problem is: If you avoid something for decades, the skill gets lost.

Most directors today don’t have the technical ability to do justice to an operatic composition, even if that is only because they are addicted to the drug of making their own power felt in the work.

IV. Two Simple “Solutions”

The miracle of a staging that does justice to an opera is very rare, as miracles tend to be. It’s a shame, because contemporary stagings offer many beautiful scenic possibilities.

If a director wants to create his own music theater, that’s what he should do, and put together the music himself. The results can be wonderful. I’ve had that happen with my own works, and each time it filled me with a deep joy to see compositions that were not originally imagined as scenic become the basis of stagings or choreographies:

- “in vain” (excerpt) with Christoph Marthaler (combined with music that wasn’t by me)

- “in vain” (complete) with Olaf Nicolai (2003)

- “Atthis” and “Haiku” with Florian Lutz (2013)

- “Atthis” and String Quartet No. 2 with Netia Jones (2015)

- “Open Spaces” (and other smaller works) with Sasha Waltz (2009)

- “Solstices” with Brigitte Walk (2023)

- “HYENA” (film) with Jack Perez (2021)

Artistically, all of these productions were honest: They didn’t act as if they were bringing an existing piece to life. It was very clear that the director was creating his own work of theater. And it was always beautiful.

Another option is the semi-staged performance of an opera composition: The music is presented adequately, and the staging implied through the use of light. That’s how the fantastic 1996 performance of “Nacht” in Bregenz was done, and how a celebrated performance of my opera “KOMA” was produced at the 2024 Salzburg Festival.

I admit, both of these solutions only get us halfway there, since they are based on a separation between composing opera and staging music theater. In the end, that’s not enough.

V. What Now?

There is a danger that I will receive applause from the wrong side.

I want to be clear: Regieoperas are (way too often!) awful. But there is something even worse: regressing to the directing tradition to which regieopera was originally opposed. The old style of illustrative opera theater is even more outdated and fulfills the dishonest desires of fascist regimes.

In art there can be no going back!

It is time to bring the consequences of Nikolaus Harnoncourt’s concept of “music as speech” to the stage for the entire field of “Western” music history—from Monteverdi’s stage works, with their deep roots in the musical rhetoric of their time, to contemporary music theater.

A person who hears the “music as speech” of Ligeti’s brilliant opera “Le Grand Macabre” will hear the desperate cries of a person for whom everything has descended into infinite meaninglessness. They wouldn’t dare to make the work ridiculous with scenic slapstick.

Every staging of Lachenmann’s masterpiece “Das Mädchen mit den Schwefelhölzern” that I have been able to see came across as unintentionally silly. It was grotesque how the directors tried desperately to prove that they were just as “modern” as the composer. If they had adhered to Harnoncourt’s “music as speech” idea, they would have realized that they were dealing with a great Romantic opera, full of emotions, with chattering teeth, angel’s wings and sho meditation.

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.

If the director of Saariaho’s opera, whose name will go unmentioned, had listened to the “music as speech” of the work, the composer would have been saved a great deal of suffering. And almost certainly the people in the audience, in the orchestra pit, and on stage would have been given something wonderful—something that was clearly missing from the staging as it was realized.

New operas only have a chance to reach many people artistically when their “music as speech” is supported and clarified by what happens on stage—not damaged or even destroyed.

True, the semantics and syntax of the “language” of music are structured in a completely different way to the language of daily life and of literature, which covers other things. It would be very difficult to order a glass of Coke in the language of music. And the other way around: For most people, the words “Kyrie eleison” mean about as much as abracadabra. The English translation, “Lord, have mercy,” is linguistically barren and incapable of expressing the depths of despair, spirituality, and hope that hides behind the words. Those qualities are revealed when the words are set to music, starting as early as the melismas of Gregorian chant.

Like many young men, when I was going through puberty I wrote emotional poems full of alienation. The first time I fell in love, I wanted to write a love poem. I couldn’t do it. Then I went to the piano and invented a series of chords that expressed my emotional state much more clearly and precisely than my words could. Since then, I have been a composer.

In traditional opera, there is a relationship between the text being set and the “music as speech” of the composition: sometimes they are nearly identical, often there is interpretation, sometimes they are in counterpoint.

The 20th century brought with it new technical possibilities. The quantum leap took place in Alban Berg’s opera “Lulu.” In Act II, during a scene change, Berg composed music for a silent film that is made especially for each performance. An aspect that was of secondary importance in earlier librettos, the so-called “stage directions,” became central to the musical-dramatic model, as essential as the words of the libretto traditionally were.

Berg did not use the orchestra as accompaniment for the silent film part. Instead, he wrote a refined retrograde structure: the second half repeats the first half exactly, but in the opposite direction, from back to front. But Lulu’s story is continued linearly; there is a counterpoint between the sonic and the visual. This “Scene Change – Film Music” section summarizes the formal conception of the whole three-part opera in a nutshell.

Alban Berg had to be content with silent film. That’s all that was available to him. Now we have much more potent technical possibilities. For example, we can compose precise rhythms in light, make fast, abrupt scene changes, electronically amplify speech and song, and much more. That deserves to be—that must be—used compositionally.

In the 19th century this was unimaginable. You can’t create a light installation when you’re still cooking over an open flame. If you need to move sets around by hand, you can’t compose a scenic rhythm.

Counterpoint doesn’t mean composing a new voice on the basis of an existing one. Counterpoint comes from the development of polyphonic structures, a web full of internal, alternating relationships. It’s called “punctus contra punctum” and not “melos contra melum” or “unitas contra unitatem.” A polyphony between the sonic and the visual must be developed as a whole, with each side influencing the other as the work takes shape. Only a single artistic individual, a creative intellect who is responsible for the whole work, can do that.

Directors can’t compose.

But composers can define frameworks of time and meaning—as Alban Berg did in Act II of “Lulu.”

A new generation of composers is growing up with video games. The musicality of changing images and the rhythms of light are in their blood. When—if—they are allowed to unleash their experiences on opera stages, not one stone will be left on another.

This must apply to the music theater of the future:

Operas are created by people who compose, and realized by people who stage.

That’s all it takes. ¶