There’s faint live music as I walk into Battersea Power Station. Around the corner from Apple’s giant, glass-fronted reception area, a man is performing an extremely committed rendition of Modest Mussorgsky’s “The Great Gate of Kyiv” on a public piano to a crowd of exactly three people, in the middle of an enormous shopping center. It’s an interesting reversal of fate: an up-town mall that once may have played classical music to keep certain crowds out, deploying the same music to lure them back.

With that strange thought at the back of my mind, I headed into a briefing about the Apple Music Classical app, which launched March 28. “It’s been a labor of love,” says Apple Music chief Oliver Schusser. The meeting room is airy, and the air in it is a little tense.

Though the logo leaves a little to be desired, the app itself feels and looks impressive, exactly as a new rollout from the world’s biggest tech company should. Apple Music Classical is a standalone app, but comes as part of £10.99 monthly subscription to Apple Music. (It’s out now on iOS, and will be released on Android at a later date.) Unlike Spotify, who recently announced their “pivot-to-video” plans (copying a TikTok-like “feed” feature by incorporating videos, and moving further towards generalized “content”), the interface of the Apple Music Classical app is reassuringly old-school, drawing mainly from the current Apple Music landing pages. The team promises playlists, introductory podcasts, and other bits of new, expert-generated content. (Though Apple’s representatives didn’t answer who any of their selected experts are, or how many there would be, they did at least say their group would be international.)

But the app’s greatest strength is in making the most of classical music’s existing idiosyncrasies.The general perception of classical music on streaming sites is that it simply doesn’t work because of metadata. It’s not that classical music has more metadata than all the other genres—compare the numbers of listed performers of a Beethoven symphony recording with the 72 songwriters listed on Beyoncé’s 2016 album “Lemonade”—it’s just that Taylor Swift songs don’t have contested Opuses, a Hob. number, a fifth movement titled “Songe d’une nuit du sabbat,” a million different revisions (looking at you, Bruckner), or a conductor. (Though, given the Nietzsche-ish exploits of “Midnights,” and Swift’s current passion for stretching her tour dates to Wagnerian proportions, it’s hard to completely rule out “Anti-Hero, The Opera (Taylor’s Version)” just yet.)

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

Apple has turned classical music’s diversity of metadata into the new app’s raison d’être. And, with so many of what Apple calls “data points”—over 50 million bits of information drawn from their database of recordings—it suddenly makes complete sense. Classical music is the perfect subject for algorithms hungry for knowledge, and their job is made a whole lot easier when a piece of music has a large variety of discrete data (a title, a tempo marking, an Opus number, a date, or a conductor), instead of forcing machines to judge whether Jacob Collier is more jazz, hip-hop, choral, or simply “genre-defying.” The all-powerful search engine has great potential, not least for music programmers. Need some other music from 1876? To compare and contrast two Symphony No. 5s? Want to build a choral concert around a concept like “water,” “love,” or “light”? Apple Music has many, many bases covered.

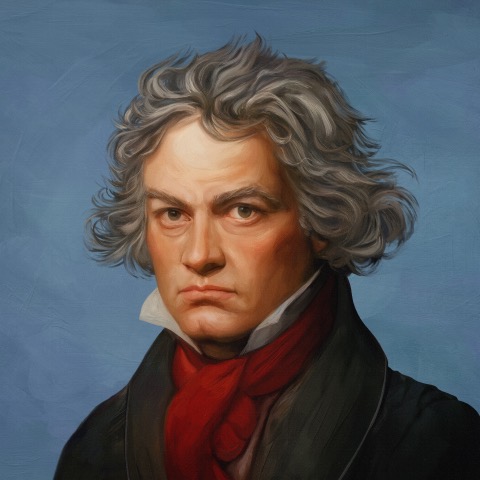

Not everything clicks, though. Viewing the continued uniformity of their house style as more important than half a millenia of art history, Apple has commissioned a series of digital portraits of historic composers. Unfortunately, they look cheap and nasty, as if the celebrated portraits of old have been shoved through a deep-fake generator. The press release boasts that the majority of these new portraits have been designed on iMac and iPad, as if that’s a virtue in itself.

The app’s boldest leap is for classical music’s recording industry. The scene in the UK reflects a growing indifference to the CD format; figures from the British Phonographic Industry show that sales of classical CDs in this country dropped 32.2 percent between 2020 and 2021 (a format that’s now also being outperformed by vinyl). Perhaps the new app is yet another hastily scribbled death notice for the classical music CD, but there are two particular developments of note that may quicken its demise. First, Apple has immediately partnered with the biggest institutions it can think of. The Berlin Philharmonic, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, the London Symphony Orchestra, the Metropolitan Opera, the New York Philharmonic, Opéra National de Paris, the San Francisco Symphony, and the Vienna Philharmonic are all partner organizations, with talk of “exclusive albums” (live recordings of orchestras licensed exclusively to Apple.) Second, performers like Alice Sara Ott and Karina Canellakis appear in the promo videos: be prepared for a tidal-wave of scheduled social media posts from your favorite artists as they jump ship from making physical CDs. Both moves are a statement of intent from a company planning on cornering this section of the market, and the question of format becomes moot if the roll-out of exclusivity continues.

With the good will of the classical music establishment, an established platform as a close relative, and the support of a company with deep pockets (turning over $394.3 billion in 2022), Apple Music Classical represents the best chance in a long while to change the mood music around streaming. But the elephant in the room is this: despite some equivocation (“We pay way more than our competitors,” Schusser offered), Apple confirmed that the remuneration structure of the new Classical App will be the same as that of Apple Music, which currently works out at an average per play rate of $0.01 calculated after 30 seconds of listening—a fraction that works for the mean average pop or hip-hop track, but that doesn’t quite suit the protracted movements of Feldman or Shostakovich. (In a later statement, an Apple spokesperson said: “We believe everyone should be paid for their art. We don’t believe in giving away music for free. We pay every label the same—large or small—and we pay more than our competitors.”) Streaming, as it currently stands, makes sense for artists with an established market presence, who don’t have to rely on the tiny revenue gained from streaming for their main income. It’s a much harder sell for everyone further down the pyramid.

But then we already knew that, didn’t we? In some ways, Apple Music Classical is a surprising, genuinely brilliant addition to the classical music ecosystem. But in one more important way, sadly, it’s extremely predictable. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.