Over the last four years, I’ve heard about half a dozen concerts of music by the composer Alvin Lucier in New York City. I have often begun listening to a piece with skepticism and left astonished. On March 25, Alvin Lucier will perform two of his works, “I Am Sitting in a Room” and “Vespers,” at the MaerzMusik Festival in Berlin. In a recent phone conversation, I started by asking him about those pieces.

VAN: In the 1981 Lovely Music recording of “I am sitting in a room,” you speak the text with a stutter. On the 2017 version, from the CD “Two Circles,” you don’t have one. Could you say something about its presence or absence? What does it mean to you?

Alvin Lucier: Oh, it doesn’t have to be there. Bob Ashley and I did a piece years ago, “Fancy Free,” talking about the irregularities that anybody’s speech has. Anybody’s speech is interesting, there are different aspects to it. My use of the word “irregularities” refers to my stuttering but it also refers to any irregularities of anybody’s speech. That’s all I can say. I wrote that text in real time, almost, on the night I did the first recording. I just decided to tell people what I was doing. The last sentence sort of came out of the blue. It’s one of those things.

You’ve said that you were inspired by a dance piece in which they described their movements as they danced.

I remembered that wrong. That was a solo piece of Trisha Brown. She was talking as she was doing it. My remembrance of that piece was she was telling you what she was doing. I’ve since looked at the video of that, she is not telling you that at all. She’s saying something else. But my recollection there was that she said, “Now I’m moving my right hand…”

I remember Steve Reich saying he doesn’t hide; he never hid his process. Those early speech pieces he made, you can hear the canons being made in real time. Schoenberg using a tone row, you don’t hear it—I mean you can hear it sometimes—but the way he’s making the piece and what you hear are two different things. I went to Tanglewood one summer years ago. Aaron Copland grabbed my arm and he said, “Your music is so direct.” I don’t hide. It’s very simple. I’m not hiding anything.

Your piece “Love Song” is also a kind of dance. Is that aspect important to you?

This piece had to be physical. They had to move around, changing the tension of the string. I suppose it has something to do with a couple, you know, tension, give and take. I think artists’ ideas, a lot of them happen in the making of the work. You have to make decisions to make the piece work. It’s not an idea that you have beforehand. So they have to lean back and come forward, I think it’s natural they move in a circle. It had to be that way to solve the piece.

In Western classical music there is a tradition of playing with space in live performance—Mahler’s offstage horn calls, Berlioz’s distribution of brass choirs, Bach placing singers in the choir loft, Vivaldi’s “eco” concerto, Tallis’s motets, and the Venetian polychoral works, to name a few. With “Vespers,” do you think of yourself as being a part of that tradition?

I think so. I was in Venice on a Fulbright in 1960. I tried to write an echo piece. Venice was famous for those brass pieces. But it didn’t work because I had two different instruments playing the echo—you need the same instrument, you know? When I wrote “Vespers,” the echolocation piece, I was making real echoes—they’re real echoes! I carried that idea from Monteverdi’s “Vespers” of 1610, he echoes two violins, two oboes, two trumpets; a beautiful piece.

In “Tapper” (2002) Lucier directs a violinist to forcefully strike the body of the violin with the butt of the bow in a steady rhythm. At first, one is attuned to the percussive sound and the steady rhythm. Eventually, complex and varied reverberations arise. A wide spectrum of overtones flicker in and out of existence. In the great Venn diagram in the sky, this piece lies at the intersection of music, scientific demonstration, sound art, and magic trick.

In a piece like “Tapper,” as the violinist Conrad Harris changed the angle of the violin, where he tapped on it, and which direction he faced there were very different effects. How much do you prescribe that in the score?

I don’t prescribe it. I tell him how to do it. I don’t tell him about the effect. We just did it down in Fort Meyers in Florida in a gallery space. He hardly moved! He just changed where he hit his bow on the violin. It changed the echoes completely. It was amazing! That piece has developed. I used to have him move around the space. Now I don’t. I’m bored with that idea, musicians moving…as long as he changes the angle slightly.

I had a student who just did a piece, he had his players walking around the concert hall. I want to tell him I didn’t think that was interesting. Sort of an old fashioned idea. Why’d he have to do that? I think he was putting a square peg in a round hole, something like that. I think you should let players stay in the same place, let the sounds move out of the instrument, flowing out into the space. You don’t gain much by having people walk around.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

When you’re traveling to Germany, are there any places you want to visit outside of the festival?

I’m so busy with the concerts. I’m a little older now; I like to rest. My wife likes to go to museums. I’ll go to a couple, but I like to rest and think, exercise. I’m on an exercise regime. I’ve got to keep myself going. I’m 85, you know.

What kind of exercise do you do?

Monday, Wednesday, and Friday I go to a trainer; we walk and run. I do something called “Big.” I do stretches every morning. I do Pilates and Tai Chi once a week.

When you’re doing your workout do you listen to music?

Sometimes I listen to the Gypsy Kings. Do you know the Gypsy Kings? I used to ride an indoor bicycle with that in the background. I love their music.

Can you tell me about an interesting sound that you’ve heard recently?

I don’t know. I have a lot of birds around my house. The bird sounds; airplanes go by. I can’t say I’ve heard any really interesting sounds, you know, anything in particular.

Are there any sounds from the past, from when you were young that had a big impact on you?

I used to go to a boys’ camp up in New Hampshire. Every August the owner would—in the evening, at dinner time—would ask every camper to leave and go back to our cabins by a route we never took before. So I’d go back and walk through the woods in a different way; and he would say, “Listen to the sounds.” This was 75 years ago! Can you believe that? I never thought about it but then more recently—with all these sound walks—[the owner of the camp] predated that by a long time. In retrospect that was very important I think.

Do you remember the sounds from those walks?

I remember some of the bird sounds. There was an evening thrush. It would reverberate through the trees, it had this beautiful reverberant environment, you’d be walking through these forests of pine trees. I remember that very distinctly. I remember a bird up on Mount Washington too, high above the timberline. I don’t know the names of birds; I never really got into that too much. I should try to identify them by their sounds more, but I don’t seem to do that.

The problem of naming reminds me of Lawrence Raab’s poem “A Cup of Water Turns into a Rose” in which at some point one of the voices chastises another:…And by the way, / you should learn the actual names / of trees. You’re always talking about trees, / and birds, and behind them the sky. Moreover, / pines don’t count.

Early on you used electronics quite a lot in your pieces. More recently you’ve been working with acoustic orchestral instruments. How did that change come about?

The only reason I started using traditional instruments was that players starting asking me for pieces. The New World Consort said, “Why don’t you make us a piece?” So I said, Well, gee, the reason I went into music was that I love music, traditional classical music, so I decided to make pieces for these players. I have to find a way to explore the natural characteristics of the sounds of the instruments. I don’t use extended techniques. There are all these pieces where you do crazy stuff to the instruments. I hardly use pizzicato! I do tap, there’s the one piece where they do tap the violin. But [in] my piece “One Arm Bandits” for four cellos, they simply bow long pitches—the beautiful sound of the cello. Most of my pieces have long sounds.

You know Jim Tenney has this nice piece for solo violin, “Koan.” He just goes up the strings: from the open G string he moves up to the D string and it’s just hearing the various qualities of each string, it’s interesting enough for me, hearing different timbres—a whole different world, each string to me is a whole different world. It’s incessant. Once the form starts it’s inexorable… you know what’s going to happen. So you don’t have to worry about anything. You can focus on the artifacts that happen. I love that kind of work.

Have you read Italo Calvino’s “Numbers in the Dark”?

I don’t know that one.

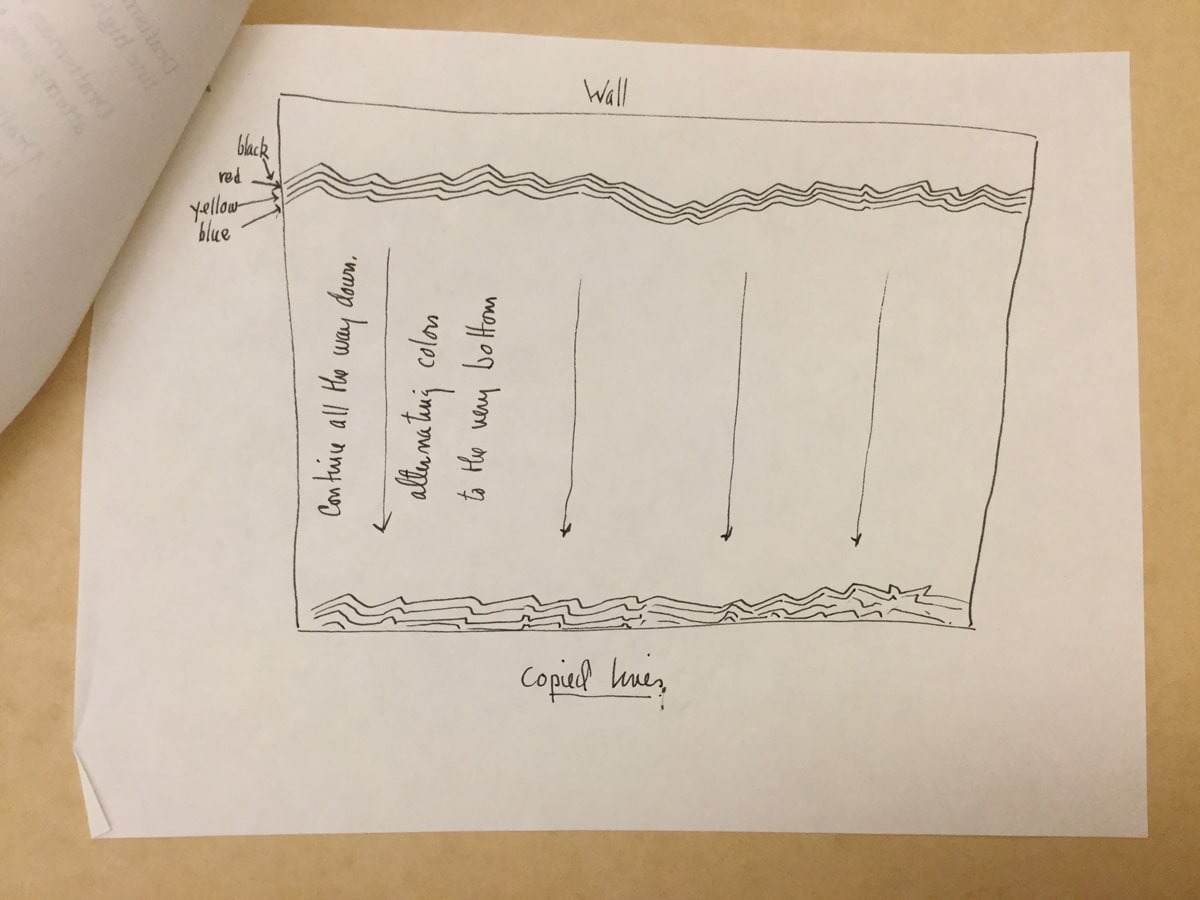

It’s a story about a young boy helping his mother to clean an office at night. It’s some kind of financial office and the boy comes across a chart of stock prices changing over time, a jagged line, and he decides that it could be a melody and whistles it. Later he encounters a man and woman working late and he performs it for them. It made me think of your “Panorama” pieces—in “Panorama II,” for example, a string ensemble is given the task of following the solo trombonist as the soloist plays a glissando whose shape was determined by the outline of a mountain range near Zug, Switzerland.

I’ll have to look at that. Thanks for telling me about that. Calvino has “If On a Winter’s Night a Traveler.” There’s a scene in there where a horse rider is riding in the dark, he’s in a big ravine; he hears another horse riding. When he stops, the other horse stops, he discovers… it’s his echo. Well, that’s a nice idea, I should remember that idea.

In describing Turin, Calvino said that “the city encourages logic and through logic leads the way toward madness.” Is there anything you have encountered that encourages logic and through logic leads the way toward madness?

I never thought about it. I’ll start thinking about it now.

Have you ever been in a dangerous place?

Not that I can remember.

Does it ever feel dangerous when you’re performing?

Not really. Sometimes if the piece isn’t working. I try to make it work, but it’s part of my life. It’s part of performance. I don’t fix things beforehand.

Do you enjoy the excitement of involving the unknown?

I do and I don’t. If the piece isn’t working, I worry about that. I don’t want to shortchange the audience. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.

Comments are closed.