Introduction

On a late night this past spring, I saw a headline in The Independent that would soon provoke exasperation in parts of the opera world, outrage in others: “Otello: Why is a white tenor leading the Royal Opera House’s new production?” I was troubled, too: the headline I’d expected to see was, “ ‘I am singing about myself’: as the Royal Opera announces a new ‘Otello,’ four Black tenors discuss why the role matters.”

I was the author of that article. But writers get to choose their own headlines about as often as sopranos improvise libretti onstage.

I already knew why the ROH had cast the white German tenor Jonas Kaufmann for the title role of Giuseppe Verdi’s “Otello”: because he’s one of the world’s greatest singers. That I’d love to hear him sing the role, and that I think the opera raises fraught questions about racial representation and diversity, aren’t incompatible positions. Although I was grateful for The Independent’s commitment to debate, I anticipated that readers would respond to the headline with the wrong kind of outrage: a defense of the star tenor’s qualifications for the role, as though his preeminence could possibly be jeopardized—as though he were a fragile Desdemona threatened by the jealous, violent forces of affirmative action! (On the contrary, there’s a profound need for leadership on diversity from all musicians of stature.) Most of all, I feared that the controversy would harm the tenors I’d interviewed, who’d never challenged any singer’s right to sing the role, and whose unique perspectives on “Otello” deserved to be heard on their own terms.

Last year, in breaking the news about the Metropolitan Opera’s decision to drop racialized makeup in “Otello,” I’d joined many in the press in repeating the critical canard about the lack of Black tenors singing the role. Then Howard Haskin had emailed me a simple claim of existence: “the Black tenors are here.” Four of them shared with me their delight in the music, hopes for change, and identification with the role of a Black man struggling within a hostile community: “I am singing about myself,” Haskin told me. (See below, “Is the Moor Black?”)

Verdi and librettist Arrigo Boito worked through years of discouragement, rewrites, and disastrous misapprehensions to complete “Otello.” It’s not an opera about second chances, but the making of opera, like that of all art, is an ongoing act of inquiry and engagement. It’s tempting to think that people who cite the success of Leontyne Price, who retired 30 years ago, as proof that contemporary racism has vanished—who demand that Otello look Black when they’re defending dark makeup and deny he’s Black when it comes to casting—don’t deserve this opera that fearlessly complicates identity, community, and hatred. But everybody deserves a second chance.

It’s no longer possible to write this story without reference to the controversy. But perhaps in doing so, I can reprioritize the singers’ own voices and try to make amends.

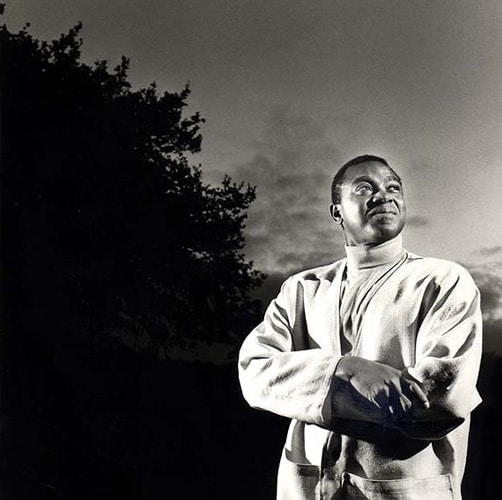

Michael Austin

Born in: Wytheville, Virginia

Lives in: Berlin, Germany

Otellos: Cleveland Opera (2004–5), Regensburg (2006), Bratislava (2011), Knoxville Opera (2012), Festival Belle Ile en Mer (2012). Upcoming engagement in Nordhausen (2017) will mark his 100th performance of the role.

Other Career Highlights: Turiddu, “Cavalleria Rusticana” (Stuttgart, 1985), Robbins, “Porgy and Bess” (San Francisco Opera, 2009)

“One has to have lived, to understand his position,” said Michael Austin, the only African-American tenor to have sung the role of Otello in a U.S. opera house. “He’s a very intelligent, powerful person, a Moor who’s a governor and admiral. At the same time, here’s a man whose whole career was the military. All of a sudden, he falls in love. He’s had very little experience with women, hasn’t experienced enough love or life to understand, so he’s easily manipulated by Iago. He has internal monologues about jealousy and bigotry, fighting with himself: ‘Why is this happening to me?’ Most successful Otellos do it at middle to later parts of their career. Now, at my age, having gone through life, lived in America, gone to Europe to have an international career, I totally understand it.”

Austin was asked to sing the role early in his career. “I’d tell them, ‘I’m not ready for this!’ They said, ‘Well, we think differently; we’ll prepare you.’ It had to do with the color of my voice—and my look. But Otello’s a part that takes time to season, not only vocally, but also mentally. You have to have stamina, sing low as well as high, sing piano, then project over the orchestra. This takes years of training, understanding how to manage the physical and technical demands. But the more you do a role, the better you understand the quality of force, the nuances, the meanings: this is what Verdi wanted, this particular piano passage.”

“When I sang ‘Otello’ in Knoxville, they sent me to do a master class at the University of Tennessee. The kids asked me questions like, ‘How is it now, compared to when you were a student?’ ” 25 years ago, Austin told them, Knoxville wouldn’t have extended him the opportunity to sing the role. One production of “La Traviata” in which he’d starred in the 1980s excluded him from the Alabama reopening, because the spectacle of a Black Alfredo kissing a white Violetta was too much for Mobile. “In the states, [opera] depends on wealthy donors, corporations, tax write-offs, someone on a board saying, ‘I don’t want to see this on the stage.’ In German-speaking countries, opera’s subsidized, not based on ticket sales.

“You go on, find strength, knock on the right doors—the doors that’ll open—and say, ‘Look, I’m qualified,’ then be the best you possibly can. And then you’ll influence so many people, who say, ‘Wow I didn’t know you could do that!’ I had great guidance, wonderful teachers and mentors. Now, younger singers give me a call, wanting to have coffee and talk. I love to give back the knowledge of how to prepare for a 30-year career. And now I have a son in the business! He’s just incredible. I’m blessed.”

Is the Moor Black?

The many medieval, Renaissance, and 19th-century concepts of Moorishness have included communities from Southern Europe, North Africa, sub-Saharan Africa, and the Middle East. Complicated as they are, there’s also the question of what Verdi himself intended. Verdi wrote of the character’s origins, “I know very well that this general, who was in the service of the great city, and known as Otello, was none other than a Venetian called Giacomo Moor. But if Signor William [Shakespeare] wanted him to be Moorish, that was the way Signor William thought about it. You can hardly have Otello dressed as a Turk, but why not have him dressed as an Ethiopian, without the usual turban?” Verdi referred to the opera-in-progress as the “progetto di cioccolata” (Chocolate Project); his publisher sent him Christmas panettoni topped with chocolate Otello figures. We can still see designs and advertising from early productions of “Otello,” along with photographs of blacked-up singers, including Francesco Tamagno, creator of the role at La Scala in 1887, who wore a wig of natural Black hair. Whether or not Otello was ever imagined as being sung by a Black tenor, there’s a long precedent for his looking Black, being accepted as Black by audiences—and appropriating Blackness.

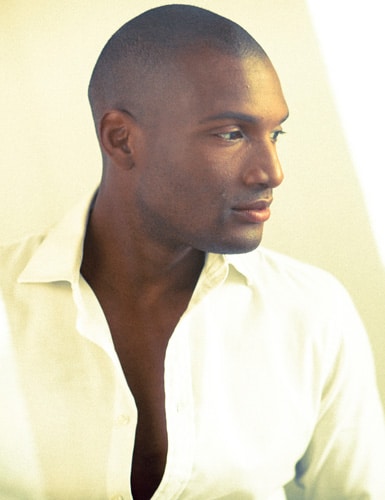

Howard Haskin

Born: Kansas City, Kansas

Lives in: Saint-Ouen, France

Otellos: Opéra de Nice (1995), Dorset Opera Festival (2011).

Other Career Highlights: created the role of Vova, “Life with an Idiot” (Dutch National Opera, 1992), “Peter Grimes” (Kent Opera, 1984; Finnish National Opera, 2010). Grammy nomination (Best Opera Recording), Il Carceriere/Il Grande Inquisitore in “Il Prigioniero” (Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra and Choir, 1996).

“I knew from the start of my career that I was a trailblazer,” said Howard Haskin, the first Black dramatic tenor ever to sing “Otello” for an opera house, in 1995. For him, “Otello” is the story of a man’s pride, disillusionment, and jealousy, but “the palpable subtext is racism and trying to be accepted as an equal. Of being better than one’s peers, yet offered second or third place—and still managing to take first place against the odds.” In 1994, when Haskin first auditioned for the role at the Opéra de Nice, the artistic team refused to hire him because he was Black. One year later, he got a frantic phone call asking him to step in for their last performance: a milestone for African-American singers that went unheralded and unreported by the press.

Dramatic tenor roles represent for Haskin “the epitome of masculinity, bordering on godhood, as one graduates to Wagner: we talk of heroes, not just mere mortal men. In a society willing to perpetuate stereotypes,” he added, these roles denote dominant masculinity: “brusque, belligerent, warrior, king.” He linked the fear of this Black male archetype to “the spate of unarmed Black men killed by police. These dominant males can only be interesting, insofar as the media is concerned, if they are viewed in a negative connotation.

“Opera and racism in general have come a long way, in that, in almost every voice category, people of color have undertaken major roles in major houses,” said Haskin. “This is a subjective business. For one person, I am the right man for the job. For another, I would not be the recommended choice. Who is right? Both of them. Who is wrong? Both of them.” It wasn’t race-based casting that he’d like to see, but “acknowledgement of those Black tenors who have sung the role and the opportunity for them to sing it in major houses.”

Haskin said that Black dramatic tenors like himself must face being “told that they must ‘grow’ into their voices and eventually into these roles. They mustn’t rush their careers; they must sing as much as possible in order to strengthen the voice and build up stamina. But then, when they’re ready, they’ll be told that they’re too old and have to make way for younger blood to take over.” But hopefully, he noted, “Issachah Savage and Limmie Pulliam look set to break the mold.”

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

Who was the first Black Otello?

While the opera houses of Europe and the United States mostly excluded singers of color during the 19th and first half of the 20th centuries, African-American classical music and opera fans packed their own theaters, concert halls, and churches. As scholars of Black music continue to write the histories, some very early African-American Otellos may emerge. What we know of the operatic pioneers of the 1950s and 1960s was chiefly chronicled by the African-American press. The Baltimore Afro-American and the New York Age reported that Detroit tenor Lawrence Watson sang the role of Otello, probably in concert, with the Buffalo Symphony Orchestra around 1956. Perhaps the very first Black tenor to sing the role in any opera house was Charles Holland, at De Nederlandse Opera in 1957; he sang it also in Hildesheim, Germany, and for a 1959 BBC television production. In 1965, The Carolina Times reported that Nathan Boyd had sung the role at the Spoleto Festival dei Due Mondi: it was “the first time he had sung in his favorite role under an American conductor—Thomas Schippers—and opposite an American Desdemona—Jane Marsh.” However, Holland and Boyd were both lyric tenors hired to sing roles inappropriate and possibly harmful to their voices.

Today, Noah Stewart is a U.S.-born, UK-resident lyric tenor, mentored by Leontyne Price, whose debut album topped the UK classical charts for seven weeks. “I’ve been offered Verdi’s hero more than six times, and I have turned it down each time,” he said. “At this stage, I am a romantic leading tenor, and I want to retain the lyric qualities to my voice throughout my career. My teachers always urged me to sing what was comfortable, rather than what people thought I should. The role of Otello is a dream role,” but given his own particular talents, he’s much more interested in singing Rossini’s lyric “Otello.” “I do think I will perform Verdi’s ‘Otello’ before I retire, but have many roles on my wish list before that time comes.”

Ronald Samm

Born in: Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago

Lives in: London

Otellos: Birmingham Opera (2009), Noorlandse Opera (2011), Opera North (2013); in concert with St. James’s Piccadilly (2015)

Other Career Highlights: Florestan, “Fidelio” (Birmingham, 2002), Siegmund, “Die Walküre” (Teatro Nacional di Sao Carlos, 2005)

“The music is so excellent! ‘Otello’ and ‘Falstaff’ are Verdi’s lasting masterpieces,” said Ronald Samm, the first Black man to sing “Otello” at a UK house, the Birmingham Opera Company. “I think ‘Otello’ by Verdi is even better than the Shakespeare play, in that the opera’s a distilled version of the play. We get all the action in one day that just slides by. You have the mix of very lyrical singing in the beginning, and it gets more dramatic as it goes on, so you have to know how to gauge that properly. By the time you get to the next duet with Iago, it’s full-on. You hardly ever leave the stage, and the energy required is phenomenal! It’s a challenge, but it’s fun as well.”

Samm has sung in productions staged in a church and set in a World War II U.S. naval base and, perhaps most intimately, in the Iraq War: “That was a promenade performance. You sing an aria or duet, and the audience isn’t 70 feet away, but right in front of you. You’re walking amongst the audience, singing, in a cold warehouse with red carpet, a huge spectacle.” There are some constants in his performances—“I bring my modern experience of being born in Trinidad and living in England for the past 28 years, trying to put that into Otello’s head”—yet he also changes each time he takes on the role. “I’m a bit of an acting animal myself; I love being onstage that way, immersing myself in a role, using what Verdi wrote, of course, but thinking how to sing it differently.

“Every time you do any role you’ve done before, you want to do it better. ‘Otello’ is extremely hard, but you enjoy overcoming the challenges.” His first time singing the role in Birmingham, he felt like “a rabbit in the headlights. It was a milestone, and it was terrifying—but you prepare the same way as you prepare Sportin’ Life in “Porgy and Bess” or Siegmund [in “Die Walküre”]. It’s a role that fits my voice, and I enjoy singing it tremendously!”

How about a Black Desdemona?

Leontyne Price, whom many critics regard as having been born to sing Verdi, said the role of Desdemona was too “bionda” (blonde) for her voice, but “I’d love to sing Desdemona on stage. Of course, the production would have to be handled very carefully by a great director.”

In 1972, African-American soprano Irene Oliver joked that she “turned white right there and then” when she got an offer to sing the role of Desdemona. She sang the first act of “Otello” for an East German TV game show that awarded prizes for guessing the “deliberate mistake” in an opera. Oliver, a Fulbright scholar who studied at the Rome Opera, defied the naysayers; she said she wanted to sing the role again. “Desdemona is a challenge to my femininity—not my skin. The problem is not what color you are, but whether you are woman enough to make the hero fall in love with you—and the public as well.” Shirley Verrett broke the color barrier in a 1981 staged production with the Opera Company of Boston. “There aren’t too many people who would ask me to do Desdemona because she is supposedly blonde, Venetian, and very fair. I played her with makeup, lightened my skin a bit, but dark hair. And I would say that once I opened my mouth, after the first few minutes, people forgot that Shirley Verrett was Black and singing Desdemona.” More recently, Talise Trevigne sang the role in concert with the Oakland East Bay Symphony.

Ray M. Wade Jr.

Born in: Fort Worth, Texas

Lives in: Cologne, Germany

Otellos: Heidelberg (2011), Kassel, Bremerhaven, and Ulm (2013), Detmold (2014), Darmstadt, Würzburg (2015)

Other Career Highlights: Metropolitan Council Auditions Winner, 1993, Samson et Dalila (Köln, 2009)

“It never felt like anything other than an honor and a privilege to be able to sing and act this role,” said Ray M. Wade Jr., during a break from rehearsing his seventh “Otello” in Würzburg, Germany. “I feel I have been blessed and chosen to perform this particular art form. It’s also a very emotional role for me to sing.

“I feel that after so many different productions and performances of this amazing role, I am more comfortable, with not only the singing but also the portrayal of this man.” He talked about the enchantment of the character—the love, passion, the frenzy—and, “I also feel I am uniquely qualified to understand what it feels like to be discriminated against, just for having dark skin, based on my own personal life experiences. I believe that brings a much more intimate and genuine, and very much needed, insight to the role. It may not work on this level with some roles but most definitely with this one!

“While [I was] in school at the University of Michigan, my teacher Willis Patterson indicated to me that, in my musical life, I would have to be two, sometimes three times as good as non-Black tenors to get jobs, especially in the U.S. This has often been the case.” Wade has sung in Europe for 20 years, but has yet to sing a major role in any U.S. opera company. “I do hope to one day have the opportunity to sing [“Otello”] in the country where I was born. I believe it is much harder for tenors of color that sing this particular repertoire…because tenors in this voice category are almost always the romantic leads. I don’t mean that other male voice categories are less important or that they don’t have difficulties, but I believe it is easier for a baritone or bass of color, because they can play the brother, father or villain roles.”

In 1993, Wade was a winner of the Metropolitan Opera’s annual Council Auditions. Now that opera houses are dropping blackface, Wade is far from the only singer hoping that they might “move toward hiring Black tenors to sing the role of a Black man. No one is talking about this, because it opens up the conversation in regards to racial inequality. And especially in the U.S., that is still not a subject that non-Blacks are comfortable with talking honestly about. Even in 2016 with a Black president.” ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.