An open air concert is a genre of its own. People see music as something that can hallow any setting and turn it into a concert hall. But a hall’s walls are not just an acoustic box to separate an auditorium from the outside world: an audience gathered in the box is a distinct social entity that varies according to what is being played on stage.

An evening of string quartets, for example, will attract an audience of more or less highbrow cognoscenti. A solo piano recital will bring an even more esoteric group that can remember the nuances of dozens of interpretations of a given work (or at least think they can). A program of operatic arias, on the other hand, will draw a more middlebrow crowd that likes its music bathed in emotion. And a symphony concert is of course a gratifying example of social unity personified by the orchestra, that model of perfect harmony.

1. Music outdoors

All these loose definitions, however, only work as socio-musical hypotheses when confined within a notional concert hall space. When classical music ventures outdoors, it naturally becomes accessible to an amorphous multitude of listeners—it’s “music for all.”

Let me stress that I use the word “naturally” in a sociological sense, as a ritual, sorry, an event, since an open air performance is always musically problematic for a very simple reason: the music divides and stratifies.

What does an open air concert look and sound like? Well, like this. For a start, anyone who feels like it can turn up and behave whatever way they like. There’s no auditorium and no concert etiquette.

For me, it’s a totally mad idea to sit on the grass, guzzling beer, chattering and drowning out the sound of a distant orchestra which is already only audible through loudspeakers. It makes no sense musically, and even less in social terms.

It comes down to liberty, equality, and freebies: to art belonging to anyone and everyone. There was a reason why Leonard Bernstein, conducting a performance of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 to celebrate the fall of the Berlin Wall—practically on its ruins, although physically in the Konzerthaus auditorium—replaced the word Freude (joy), in the last movement’s “Ode to Joy” with Schiller’s original Freiheit (freedom), which had been banned by a censor in the poet’s time.

Or take the world tour undertaken by the famous three tenors—José Carreras, Plácido Domingo and Luciano Pavarotti—in 1996-1997. Watch them take the top B at the end of Puccini’s “Nessun Dorma,” and the stadium crowd’s ecstatic response. Is it beautiful? You bet it is. Is it stupid? Oh yes.

But it is also live, warm, spontaneous—joy and freedom at the same time. You can hear this in a recording of Seiji Ozawa’s A Gershwin Night at Berlin’s Waldbühne amphitheater in 2003: listen to the solo clarinet at the start of “Rhapsody in Blue,” that iconic rising glissando over an octave—doesn’t it sound completely different in a woodland setting as opposed to in a concert hall?

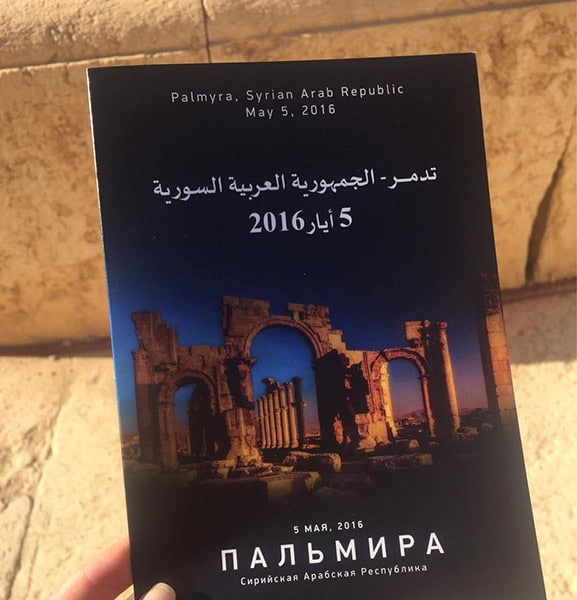

Let’s now look at the program for our Palmyra open air concert. The orchestra was conducted by Valery Gergiev, a crony of the authoritarian usurper Vladimir Putin; the soloist, cellist Sergei Roldugin, controls the money and assets of the same usurper. Keeping this in mind, it’s already hard to to trust the concert title, which is indeed a fine one: With a Prayer from Palmyra: Music Revives the Ancient Walls.

Of course, beauty may well be in the eyes of the beholder, but the opposite is also true. Let’s say that everyone is free to hate his country’s government, and that it’s a private matter as to who usurped what in Russia and how much money they moved. But let’s also look at, and listen to, the concert more closely.

2. In lieu of a review

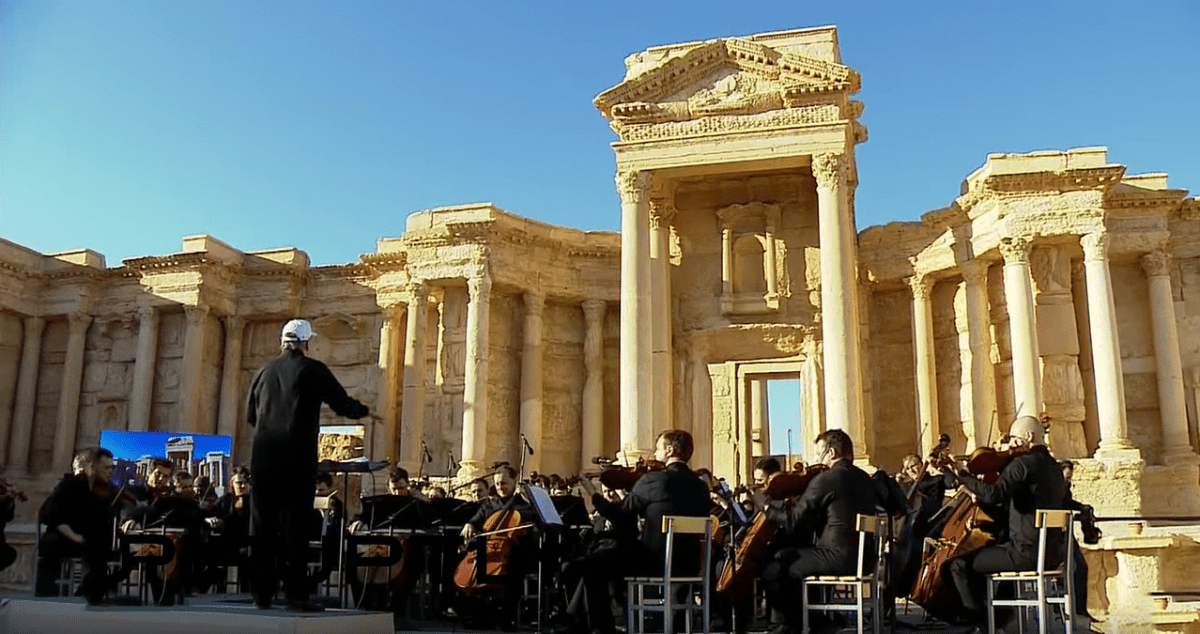

I suspect that no concert, whether in or out of a building, ever started with a 15 minute solo violin piece with a silent orchestra on stage. This in itself should warn us that Palmyra is no ordinary performance. After all, the (insert the glorious name of the relevant Russian artillery) guns have only just fallen silent, and the muses’ voices cannot immediately ring out in chorus, let alone orchestra. We need to start with a single human voice.

As Valery Gergiev has told us, Bach’s Chaconne for solo violin from his Partita No. 2 symbolizes the greatness of the human spirit. It was indeed appropriate to play it in memory of Khalid al-Asaad, Palmyra’s retired director of antiquities, who was beheaded by ISIS orcs.

I also can’t fault violinist Pavel Miliukov, who gave an excellent performance of the Chaconne: with gravity, a sense of pain and a distinctly socio-political sound, as the occasion undoubtedly demanded.

Things, however, went rapidly downhill after Miliukov. Sergei Roldugin scraped through the joyful quadrille from Shchedrin’s opera “Not Love Alone” badly and out of tune. What was this music doing here, in this devastated place desecrated by mass murder? What message did it give? That in Palmyra today you can find not hell alone, but, as Shchedrin’s gloss to the quadrille puts it, “the happy divorcee Katerina dancing with one man after another”?

And what did Prokofiev’s Symphony No. 1, that jokey juvenile imitation of classicism, symbolize for Palmyra? In its inappropriateness it was reminiscent of some national flag being raised by an intrepid expedition in a remote godforsaken end of the earth.

Perhaps, of course, the music was meant to be that flag. The simpler the gesture, the more easily it reaches its target audience. It was as though after the liberation of Palmyra from the inhuman barbarians, what was needed first was the panhuman music of the panhuman Bach as a sign of panhuman grief—after which we could play our own, Russian music. We beat the barbarians, drove them out of this holy place and polished them off with our Prokofiev’s Symphony No. 1.

But even this simple correlation was probably unintentional. The Prokofiev Symphony was probably chosen because it only required a small orchestra and, in the second, because they needed a straightforward and well-established piece that wouldn’t fall apart in adverse weather conditions. And it didn’t fall apart; although that is just about the only positive thing one can say about the performance.

Let’s be fair, it’s difficult to play in such heat: the instruments get hot; the humidity affects them; they need extra tuning; the players’ fingers slip; strings break and so on. Shchedrin’s Quadrille didn’t work at all, but the Prokofiev wasn’t too awful, and to be honest they can play just as badly in the Mariinsky itself.

3. A Partita for the president

It seems to me that the only person who could even think of giving a concert in such a place is Valery Gergiev. His career is in no need of a boost—he is already the possessor of as many posts, regalia, and contracts as anyone could hope for. But it would be good to also appear as a dove of peace, or at least an ambassador of goodness and beauty, especially in the eyes of the Western musical world, which frequently frustrates this selfless servant of the muses.

But here too the Russian president’s confidant did not have his own way completely. Roldugin’s solo (and Shchedrin’s Quadrille, for that matter, for what the soloist wanted to play was what had to be played) can’t be explained as anything other than an encouraging gesture by Putin towards his treasurer. You’re getting flak from the professional music community for your cosy relationship with Putin? Then come and play in this historic place with Gergiev. The maestro assures you that you will be there with him on the summit of the musical Olympus, and your critics are just a bunch of envious losers.

If as a listener you don’t know much about music, then you start asking, “that offshore cellist guy—is he any good? If Gergiev himself is accompanying him, maybe that means he’s not bad.”

Well, Roldugin is bad, and he hasn’t played with Gergiev for many years, because Gergiev only performs with high class soloists, and Roldugin hasn’t been one of those for a long time (although he was once).

Wearing my music critic hat, I have to tell you what Russian state TV didn’t show: the sound engineer also did a terrible job. But why write anything about the musical side of a performance that was nothing like a proper concert in terms of either length or program? I am pointing this out in order to show that music was ultimately out of place here.

As previously stated, an open air concert is in some sense a contradiction in terms, since its inherent inclusive quality contradicts the general customs of classical music, which hides from the general public behind walls (even as it invites the public to storm said walls).

But here in Palmyra there was, of course no inclusion but rather, obvious exclusion. The audience was bussed to the ruins of the ancient amphitheater under the baking sun, where it was sorted into groups (more thoroughly, in fact, than the orchestra): Russian military personnel (those who supposedly expelled ISIS from the city); local religious leaders (representing the right sort of Islam, not the one preached by ISIS); and local children (who suffered a lot and killed no one, unlike children from the same place who were involved with ISIS). And senior Russian officials. And a TV speech by an ostensible peacemaker. And an out-of-tune song from liberated little girls in national costume, and well-organized applause in all the right places. It was an immaculately staged production.

4. How to stage “reality”

One of Stanisław Lem’s novels is called Peace on Earth. It has a simple plot: all the weapons on earth are loaded onto rockets and dumped on the moon, to put an end to the arms race, and all countries pledge to never visit the moon and find out what goes on in whose sector there. But the robots who service the weapons develop using what Lem calls necroevolution—the ability of non-living things to reproduce themselves and evolve—and eventually threaten Earth.

In Russia, we don’t really know what is going on in Syria. Yes, ISIS is absolute evil; nothing is worse than ISIS. But how do the warring sides actually interact? Couldn’t this absolute evil attract another evil—Russian militarism, which has been flattening Syrian cities as effectively as ISIS, and on some occasions to its obvious benefit?

Why think about this as you watch the concert on TV? Because Russian TV is creating a Russian moon, an opaque parallel reality. It is in this reality, and only here, that a great conductor and first class cellist honor the memory of the righteous tortured by Islamists, and use their high art to bring peace to a ravaged place like Palmyra.

There is a certain off-the-wall shamelessness in this—the “Crimea Is Ours” gang and the Panama moneybags praying for the dead Khalid al-Asaad. It is a kind of spiritual pillaging. I admire the media-savviness of the Russian world: it is capable of messing up any idea, perverting any impulse. It is not hard to achieve this: you don’t just broadcast an event as it takes place; you organize the event so as to get the right pictures.

Meanwhile, in the case of an ordinary open air concert, the music, while obviously facilitating the event, is otherwise irrelevant. It provides an ambient background, a pleasant acoustic carpet to lounge on. You might not even notice it. All it does is underline the strangeness of the situation: it’s not normal to use classical music in this way—in a stadium, a park, a city square or beside a canal—but this is how we use it today. Because, to quote Schiller’s “Ode to Joy,” “Deine Zauber binden wieder, was die Mode streng geteilt”—“Thy magic power re-unites / All that custom has divided.”

That’s how you can tell what is alive and what is a product of what Lem referred to as a necroevolution. A society that is alive observes customs, rules and limits in everyday life, but breaks them in its art. In Putin-organic forms of life, everything is the other way around.

But there’s good news, too: now the divorcee Katerina has seen not only northern Palmyra. ¶

Comments are closed.