From 1991 to 1994, Carlos Sandoval, a man with thick grey hair, brown eyes, and wide shoulders, was an assistant to the American-Mexican maverick composer Conlon Nancarrow. It was a defining, if chaotic, time for Sandoval. “[Nancarrow] was always drinking, composing, reading, just throwing away books, newspapers, scores, whatever,” he said.

Nancarrow’s tendency to discard at random was particularly problematic, since one of Sandoval’s main responsibilities was keeping track of his materials. The studio was not an orderly place. Even so, when Sandoval left it—he refers to the studio as “the office,” as in the “one and only office I had in my life”—he was requested to delete information about Nancarrow’s documents from his personal laptop. However, “knowing [Nancarrow’s family’s] sloppiness surrounding Conlon’s matters, I kept a floppy disk with all the databases,” he said.

Later on, technical confusion within Nancarrow’s family caused the list of documents in his archives to be deleted. Nancarrow’s wife Yoko got in touch with Sandoval, who told her he still had a copy. Sandoval found out then that Nancarrow’s papers would be sold to the Paul Sacher Stiftung, a foundation that collects contemporary music manuscripts and other documents, in Basel, Switzerland. Sandoval forwarded this information to the American composer Charles Amirkhanian, and that was the end of his involvement. (Citing the confidentiality of sales to the Paul Sacher Stiftung in general, Amirkhanian declined to comment for this story.)

The sale caused a stir in certain Mexican cultural circles. Nancarrow had fought in the Spanish Civil War for the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, and because of this, the U.S. government had refused to renew his passport. He had then become a Mexican citizen and one of the country’s first major experimental composers. In the January 11, 1995, issue of the paper La Jornada, the cultural critic Pablo Espinosa deplored the sale, writing, “It is urgent that Mexican cultural authorities, as well as the Mexican government, take action on this matter so that this heritage can continue in Mexico.”

The sale of the papers affected Sandoval, too. In a letter to the editor, published in La Jornada on January 19, he noted, “Indeed, the loss of Nancarrow’s artistic legacy represents a catastrophe (one more) for our country.” He cited the lack of appreciation for Nancarrow in the Mexican cultural-political sector, saying that most of the interest in and research on his work had originated from abroad. In his opinion, the short-sightedness and petty politicking of people in positions of power were mainly to blame for the loss. “I vote for Nancarrow’s departure. Europe is paying what it’s worth and deserves it. And musical world heritage deserves it too,” he wrote.

However, according to Sandoval, the Paul Sacher Stiftung handles its materials problematically in other ways, despite being free of political concerns. When I first reached out to him in June asking about the archives, he responded quickly: “The Paul Sacher Stiftung, despite taking good care of Nancarrow’s archive, is NOT a cool institution. They keep Nancarrow as morally, musically, and physically ‘theirs.’ I mean, they paid for it, but this is humankind[’s] property.”

In August, I met Sandoval at a café near Berlin’s now-defunct Tempelhof airport complex. I asked him what he meant when he said that the Stiftung kept Nancarrow’s archives as “morally” theirs. He was criticizing the foundation’s policy of keeping documents under wraps on their premises. Documents there are only made available to researchers who can propose a specific topic and are subject to approval. Furthermore, they must be viewed at the foundation, and then usually only on microfilm. He felt that the Stiftung’s policy of pre-approving researchers and topics gave it too much leeway to decide what kind of work about Nancarrow gets done, amounting to a control over his legacy—a failure of “academic morals.”

Sandoval clearly felt ambiguous about the Paul Sacher Stiftung more generally. On the one hand, he acknowledged its high-quality musicological research and seriousness and care with the papers. Unlike Espinosa, he didn’t think Mexican institutions had more right to Nancarrow’s manuscripts than the foundation had. And he disagreed with my suggestion that the works might have a special power in person, compared to on microfilm. “They don’t have this Romantic idea of coffee marks, cigarette marks. They are very clean,” he said.

On the other hand, the foundation’s total control of Nancarrow’s archive bothered him. He was surprised when I mentioned that Paul Sacher, who founded the Stiftung, was a pharmaceuticals plutocrat with a fortune once estimated by The Economist to be in the billions of dollars, making it a strange home for a composer with Socialist beliefs. After we met, a request came to his attention which seemed to imply that there were questions concerning the completeness of the archives. Sandoval felt that, since he had catalogued Nancarrow’s papers, there was a lingering, untrue implication that he had secretly kept documents for himself. (Before the papers were sold, Sandoval was offered a position as Director of a hypothetical Conlon Nancarrow Foundation in Mexico. He declined, saying that the post had only been offered due to a cultural-political power struggle. “And I’m not an office guy,” he told me.)

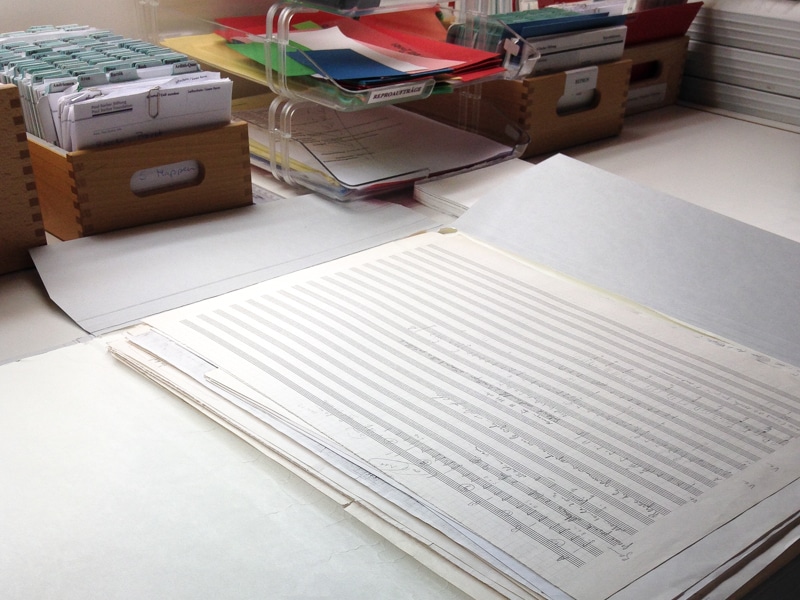

In February of 2007, Sandoval said, he approached Dr. Felix Meyer, the Director of the Paul Sacher Stiftung. He is still in possession of his own orchestral transcriptions of Nancarrow’s player piano composition “Three Movements”; while the arrangement was done by Sandoval, Nancarrow had made comments and corrections in his own handwriting. They show a part of the composer’s creative process. Sandoval thought these documents might be of interest to the Stiftung; he was also broke. So he offered to sell them.

Dr. Meyer declined to purchase the papers. But he said that the Paul Sacher Stiftung would be happy to accept them on donation. (When I asked him about the exchange, Dr. Meyer said he couldn’t remember this conversation.) Sandoval decided not to sell. He found it contradictory that the documents were considered irrelevant when associated with a fee, and relevant if they had been offered up for donation. Also, in his possession, they would be easier to share with others. Still, he seemed embarrassed about the episode. He worried that it would make him look greedy, or as if he was selling out his beliefs. I told him I thought any working musician would understand the feeling of struggling to make rent. For many composers and heirs, financial remuneration was the main reason to sell documents to the foundation—in Sandoval’s estimation, this was true of Nancarrow’s family as well.

The Paul Sacher Stiftung is universally recognized for its dedication to the materials in its possession, and every source I spoke with for this story praised the quality of its staff and their research activities. However, the foundation also regularly outbids other institutions in order to purchase complete archives of important contemporary composers. It holds manuscripts of internationally renowned musicians in Basel—some of whom, such as Bela Bartók or Anton von Webern, are essential figures in other countries’ cultural histories. Its specific policies for outside research are unusually restrictive. Its wealth stems from a past of problematic corporate policies. Is the Stiftung helping or hurting the world of contemporary music?

The first major purchase for the Paul Sacher Stiftung was Igor Stravinsky’s complete archives, in 1983. In a New York Times article, “New York in Race to Keep Stravinsky Archive,” the paper describes a bidding war. The New York Public Library, where the papers were on deposit, the University of California at Los Angeles, and the University of Texas prepared offers—of $1.2 million, $1.5 million, and $2 million, respectively. Sacher offered $3 million. Though Zubin Mehta and then-NYPL President Vartan Gregorian staged a last-minute drive for donations, insisting that the papers needed to stay in America—before his death, Stravinsky had become a U.S. citizen—Sacher won the bidding. According to his biographer Lesley Stephenson, the final amount he paid, including fees, rose to over $5 million. (Through representatives, Mehta and Gregorian declined to comment for this story.)

The purchase provoked heavy debate. The musicologist Hans Jörg Jans later wrote, “the purchase [of Stravinsky’s papers] by the previously-unknown Paul Sacher Stiftung was commented on, by the international—and in particular the American—press, in a condescending or even hostile manner.”

The Swiss conductor and arts patron Paul Sacher was a personal friend of Stravinsky’s, and so there was a clear logic behind his purchase. It was a spectacular way of getting the Paul Sacher Stiftung off and running. And most of Sacher’s early collecting was based on his relationships. As the foundation continued acquiring archives, however, it branched out to composers to whom he had little personal connection, and even antipathy. The Swiss pianist and musicologist Christoph Keller told me that during World War II, Sacher, whose tastes ran to the Neoclassical, had declined to commission a work from Anton von Webern, who badly needed the money. After his death, however, the Paul Sacher Stiftung purchased Webern’s archives.

Keller has also recorded a CD of the complete piano and chamber music works of the East Berlin Communist composer Hanns Eisler. “I know that there were negotiations for the archives of Hanns Eisler, and it would have been very strange for him to get the archives of a Communist composer, whom he really didn’t understand. Luckily that didn’t happen,” he told me. The works are now stored in Berlin instead where, Keller said, they belong.

Keller’s comments about belonging—and my ongoing conversations with Sandoval—raised an important question. Does it matter where a composer’s manuscripts are kept? In a speech for his 80th birthday, Sacher said, “The Stiftung is my attempt at contributing something, after my earthly existence is over, to the reputation and importance of my father city.” Possession of musical manuscripts (or any important works of art) adds to a city’s cultural clout. But beyond that, does the music world have a legitimate interest that manuscripts be kept in a particular place, perhaps one with a biographical connection to the composer?

“The New York Public Library collects in a manner that often will emphasize New York origins,” Jonathan Hiam, the Curator of the American Music Collection there, told me. “If we see that there’s a composer who really seems much more tied with the West Coast, and there wasn’t any particular tie to New York, often we would ask that question up front of the donor or the seller: Why wouldn’t you put this out in California?”

The papers of Elliott Carter, a New Yorker, are stored in the Paul Sacher Stiftung. John Link, the Senior Vice-President of Carter’s Amphion Foundation, said that concerns other than location took precedence for Carter. “When Carter sold his papers to Paul Sacher in 1988, he used the proceeds to fund The Amphion Foundation, which makes substantial grants to new music organizations around the world. …It was Elliott’s hope that the foundation’s ongoing support of contemporary music might offset the inconvenience to American researchers of his papers being in Basel,” he wrote me in an email.

“The Carter papers are not the Elgin Marbles; Carter was well aware of the foundation’s policies when he made the decision to sell his papers, and those policies have not changed,” he added.

Another prominent New Yorker whose works are stored in the Paul Sacher Stiftung is Morton Feldman. At the University at Buffalo, where Feldman once held the Edgard Varèse Professorship, only a few scattered documents are left. John Bewley, the archivist in the Music Library, said he wasn’t familiar with the details of the sale, but added that he has “had a very good working relationship with the Sacher Stiftung and they’ve been very cooperative about sharing information and fielding requests from patrons who begin their research with inquiries here.”

In a 2014 interview with CompositionToday, Dr. Meyer, the Paul Sacher Stiftung’s director, said that he had come close to acquiring the John Cage archives. Negotiations had gone so far that a draft contract was drawn up. But of all contemporary composers, was there ever as intimate a connection between a composer and his city as that of Cage and New York? In countries such as the U.S. and Mexico, it may perpetuate stereotypes of classical music being an exclusively European art form when even the most important North American composers’ manuscripts end up overseas.

I asked Meyer for his thoughts. He said that it is impossible to establish such a thing as a composer’s “spiritual home.” Using the example of Cage, he called him a typically West Coast composer in attitude and said that trying to establish one rightful home for his manuscripts would be pointless quibbling. (Dr. Meyer also told me that Carter felt his music was often unfairly written off as too European in the U.S.) As Director, he is often criticized by commentators who believe that papers in the Stiftung’s collection belong elsewhere. For him, this view is hypocritical—the quality of the foundation’s scholarship and research justify the presence of internationally important archives. He added that since Western society has accepted capitalism as its dominant organizing system, it is strange to argue that it is unfair when music manuscripts go to the highest bidder.

At the Paul Sacher Stiftung, you are required to present a research topic before making an appointment. While this is a reasonable requirement in, say, tracing the origins of a piece from sketch to finished product, it results in somewhat of a Catch-22 for biographical research. How can you know what you’d like to get out of the archives before you even know what’s in them? To date, there is no complete catalogue of all the documents in the Stiftung. (Meyer said they were working on digitization, but that it would take time, citing the millions of documents in the collection.) Keller told me, “At the Sacher it is relatively hard to get access to things. It’s not completely simple. It’s not a public library. And basically, they’re not accountable to anyone.”

He personally had done Webern research there, and praised the foundation for being friendly to him, despite a scathing article on Paul Sacher’s musicianship that he published in 1986. But, he said, “If they’re not interested, if [the research] doesn’t have anything to do with them—the Paul Sacher Stiftung, or a project that they’re collaborating on—than it’s possible that you can’t see the archives at all. They’re—how should I put this—buried there, the archives.” Hiam, the NYPL curator, told me, “It does make access difficult. It’s a much more mediated relationship with the institution.”

Meyer said that he couldn’t think of a particular instance where his staff rejected a research proposal, but emphasized to me that the Stiftung would only make documents available to prepared visitors. He used the example of a high school student, saying that if a young adult had only vague knowledge that the Stravinsky archives were kept there, that probably wouldn’t be enough to view them.

The opposing philosophies of the Paul Sacher Stiftung and the New York Public Library concerning access seem close to irreconcilable. Carter clearly took the former’s perspective. In a 1990 interview with Jonathan W. Bernard in the journal Perspectives of New Music, he said:

[Sacher’s] library…is much better appointed, staffed, and organized than any library that I know in America concentrating on 20th-century music. I was soon persuaded to accept his very generous offer. I had not previously thought of selling, and no American library had ever mentioned buying, my material; instead, the New York Public Library, where most of my material was on deposit, is constantly asking for donations, which now I can afford to increase. …

The Stiftung is very specific about who can get in and who can’t. They won’t let in people who can’t prove that they’re bona fide scholars. Libraries over here usually don’t have enough money for good security.

Discussing the NYPL’s philosophy, Hiam said, “We think it’s important to have materials open to the public, because we don’t know who’s out there, and what they need—what might inspire them.”

In response to a general inquiry I sent to the Paul Sacher Stiftung in June, Ute Vollmar, the assistant to Director Dr. Meyer, wrote, “Understandably, we cannot comment on financial matters.” Close to the end of his life, Sacher himself uncharacteristically told a journalist that he had “certainly sunk 200 million Swiss francs into the foundation, probably more.” This amount included renovations for the foundation’s facilities, to the tune of 10 million Swiss francs, and an additional 11 million Swiss francs (the exchange rate for $5 million at the time) for the Stravinsky archives. In the early years, the foundation made several other major purchases. The rest of the funds were used for its endowment, ensuring its survival in perpetuity. (Dr. Meyer told me that 200 million francs was a very rough estimate, probably produced on the spot in order to keep the reporter happy, but didn’t give details about the Stiftung’s budget today.)

If accurate, this amount would be particularly impressive considering the narrow focus of the foundation. The Paul Sacher Stiftung’s endowment supports a staff of 17, and its other activities are generally limited to in-house research, organizing seminars, and providing scholarships to musicologists. (Like the NYPL, it collaborates with donors for major manuscript purchases, such as the 2014 acquisition of Kaija Saariaho’s archives.)

In comparison to its institutional competitors, the Paul Sacher Stiftung is non-bureaucratic, and therefore flexible. This was an explicit goal of Sacher’s. When public institutions elsewhere try to compete for manuscripts, they suffer from a slower decision-making process and a louder cacophony of divergent interests, similar to the differing speeds of action between governments and corporations.

This contributes to a sense among the people I talked to that the foundation is by far the best-equipped in the world to buy contemporary music manuscripts. Hiam said, “They were very aggressive and had what seemed like pretty good resources for such a long time, that that was always kind of an advantage. They could pony up a fair amount of money. And people understood that. In other places, you look and think, Well, we’re not going to be able to do that.” In the competition for composers’ archives, the Stiftung enjoys both a material and psychological advantage.

The Paul Sacher Stiftung is, in many ways, a reflection of the personality of its founder. Paul Sacher was born in 1906. His father, whom he found unambitious, worked at a shipping company, and his mother kept a tailoring studio. As a child, he learned the violin. After studying musicology and conducting in Basel, he founded the Basler Kammerorchester in 1926. The ensemble focused on early and contemporary music, omitting much of the standard Romantic repertoire that other groups in Basel and around the world focused on and making a name for Sacher in the process.

In 1932, Emanuel Hoffmann, an heir to the pharmaceutical company Hoffmann-La Roche, died in a car accident. His wife, Maja Hoffmann-Stehlin, was left a young widow. Sacher met her through the wealthy circle of arts patrons he had cultivated in his work with the Basler Kammerorchester. She had many suitors—Sacher was empathetic and tactful in courting her. They were married in 1934.

Hoffmann-Stehlin was an engaged patron of the visual arts. After they were married, she asked Sacher to manage her stake in Hoffmann-La Roche. Sacher was highly enthusiastic about and involved in the business. On his own initiative, he organized a purchase of a controlling stake that returned the Hoffmann family to the board in the conglomerate, saying, “If all my money is in a company, then I want to be able to give the orders.” Sacher joined the corporation’s Board of Directors in 1938.

The musicologist Friedrich Geiger has examined the bureaucratic minutia of Sacher’s time as President of the Schweizerische Tonkünstlerverein, a musician’s union, during World War II. Refugees were arriving in Switzerland from Germany, and Sacher was worried that qualified musicians among them would pose a threat to the livelihoods of Swiss composers. Geiger’s research shows Sacher as an effective bureaucratic infighter. In one rather humiliating case, he pressured a German refugee composer to renounce the performance privileges that would normally have been available to him as a precondition for joining the union. (The composer’s works were later performed as part of the Verein’s music festival; permission was first granted years after he had been naturalized as a Swiss citizen.)

In the meantime, Sacher’s marriage to Hoffmann-Stehlin had made him rich, and he used his newfound wealth to build a luxurious life for his family while simultaneously funding his artistic activities. “Most of all I feared poverty, because, as I very quickly saw, it meant dependence and vulnerability, ruling out the freedom to make one’s own choices,” he wrote later. He commissioned a vast array of new works for the Basler Kammerorchester, many of them masterpieces, and injected cash into the group when proceeds failed to cover the costs of doing business. His by all accounts generous philanthropy made him popular. In a gorgeous illustrated letter from 1989, the kinetic artist Jean Tinguely wrote to Sacher, simply, “Dear Paul, thank you for the caviar. Yours, Jeannot.”

Sacher once said, “I didn’t earn my fortune. If a person comes into money through happy coincidence, then he needs to understand that it’s a loan and that he needs to do something with it.” What Sacher did with his fortune was very much in line with his own tastes, however. And despite the advantages he gained from his marriage, Sacher was far from a faithful husband. He had “dozens of women” in his life, and at least two parallel families. At some point, Hoffmann-Stehlin found out—and decided to ignore it, though it clearly troubled her. “Paul is a secretive person. I wonder if anyone knows him entirely?” the artist Niki de Saint-Phalle once wrote.

Reading the thorough, honest, and generally sympathetic biography Symphony of Dreams: The Conductor and Patron Paul Sacher, by Lesley Stephenson, it’s easy to note that Sacher benefited from the sexism of his time. A woman marrying into enormous wealth and then being unfaithful to her husband would likely have been subject to far greater scrutiny than Sacher, whose affairs were generally accepted as being the prerogative of a great man.

Sacher’s musical legacy, too, is a subject of some controversy among the people who knew his work. Stephenson presents him as a successful conductor with a few critics, and a limited repertoire. But Keller, the Swiss pianist, told me, “None of the musicians who played under him thought a lot of him as a conductor.” He added, “I think he was much more talented as a businessman than as a musician.”

The tranquilizer Valium turned Hoffman-La Roche into a major global pharmaceutical player. Sacher’s natural discretion and good business instincts made him a natural fit at the firm, which was also notoriously secretive. In the 1970s, it was hit with two scandals. A whistleblower named Stanley Adams went to the then newly-formed European Commission with allegations of price fixing on vitamins—according to him, Hoffmann-La Roche had been agreeing on amounts with its competitors, then secretly undercutting them by offering clients off-the-books “fidelity contracts.” (Adams also claimed that at one point, Valium was being sold in the U.S. at a 1,000 percent markup compared to Great Britain.) When the European Commission accidentally leaked Adams’ name to Roche, the company pressed charges of industrial espionage. He was arrested on the Swiss-Italian border and kept completely incommunicado for several weeks; during this time, Adams’s wife committed suicide. He lost his sources of income, and spent time in Italian prison due to outstanding debts. Asked to comment on the affair, Sacher said, “I didn’t even know him.”

Despite this, Adams felt Sacher’s influence strongly, if indirectly, as he was deciding whether to go to the authorities about illegal trade practices. He wrote, “There was nobody I could report Roche to who could take action. …And Roche was a great patron, a great donator to good causes. The city of Basel in particular had good reason to be grateful to Roche. Roche imported orchestras to play to the citizens of Basel.” (Adams was later sentenced to jail time for attempting to take out a hit on his third wife to access her life insurance policy.)

In 1976, an explosion went off at a factory in Seveso, Italy, releasing a strong poison, dioxide, into the air. No humans were killed, but animals dropped dead, like in a biblical plague, and children suffered from skin disorders. The factory was run by a company called ICMESA, a subsidiary of Givaudan, in Geneva, which was, in turn, a daughter company of Hoffmann-La Roche. The event was a public relations disaster: The corporation declined to comment for days at a time, and when he did speak to journalists, then President of the Board of Directors Dr. Adolf W. Jann downplayed the effect of the poison on children, once commenting that they were only crying because of the needle pricks from blood tests. In the 2005 film “Gambit,” about the crisis, Jörg Sambeth, the former technical director of Givaudan, said, “The President had absolute power and the full trust of the heirs, especially of Maestro Sacher.” Sacher himself, who chose Jann for his post, once said, “Delegation is a great art.”

I asked Sabine Gisinger, the director of the film, to what extent she thought Sacher influenced Roche’s reaction to the Seveso disaster. “I tried to find out how much [he] was involved—without success,” she wrote me. “I looked through his correspondence at the Sacher archives in that time period and didn’t find the slightest mention of the events in Seveso—which of course speaks volumes. I suspect that, to put it cynically, these kinds of ‘lowly things’ didn’t interest him. But as I said, I couldn’t find any sources or witnesses.”

Towards the end of his life, Sacher became aware that his connection to Hoffmann-La Roche would influence his legacy after death. He told Stephenson, “I don’t have blood on my hands, but I have money on them. And of course this part of my biography has hurt my reputation.” Inversely, however, Hoffmann-La Roche benefited from Sacher’s artistic activities. The cultural landscape of Basel today is greatly influenced by Sacher—he helped bring about its Musikademie (where I studied composition from 2011 to 2013), Schola Cantorum, and Jean Tinguely Museum. It is also shaped by Roche, which provides financing for large swathes of Basel’s cultural life, the Lucerne Festival (Givaudan is also a supporter) and attendant Roche Commissions, a workshop at the Salzburg Festival, and more. His art and music world connections made Sacher a subtle, effective cultural ambassador for the conglomerate. In turn, these donations increased the pharmaceutical firm’s soft power and cultural standing, a valuable deterrent in cases such as Adams’s.

The Paul Sacher Stiftung is endowed solely through Sacher’s personal fortune. But the presence in Basel of manuscripts from leading composers throughout the world, made possible with Roche earnings, also shows the company’s soft power. Several company officials, such as André Hoffmann, sit on the Stiftung’s board, and the company contributes yearly to defray some small expenses, such as microfilm upkeep, Dr. Meyer told me. (The Paul Sacher Stiftung operates completely independently of Roche, however.) When the negotiations on the Stravinsky archive were finally settled, Sacher’s representative Albi Rosenthal is said to have cabled him: “Valium vincit omnium,” or “Valium triumphs over all.”

On a recent warm, cloudless day, I hiked up the steep incline to Basel’s touristy Muensterplatz district, where the Paul Sacher Stiftung is located. From the nearest vantage point, I looked out over the green Rhine river. Downriver was a large, clearly marked Novartis skyscraper. In the other direction, an even larger, white tower had no sign on it. Walking by later, I realized it belonged to Hoffmann-La Roche. The campus is so extensive that there is a public-transportation bus stop named after the corporation.

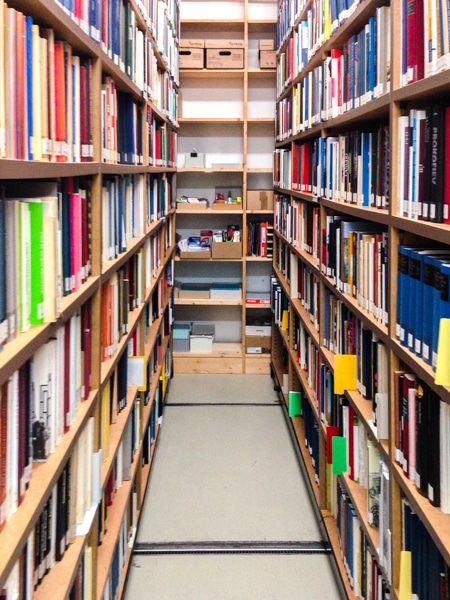

The foundation building is small, with no sign except a bronze plate next to the doorbell. A steep staircase leads to the reading rooms near the entrance, and the color scheme consists of whites, grays, and wood browns. Dr. Meyer, a man with short dark hair, in a blazer, blue shirt, and jeans, had heard about my inquiries to John Link, the Vice-President of Carter’s foundation, and seemed suspicious of me. He immediately launched into a spirited defense of the Paul Sacher Stiftung’s collecting practices.

With Sandoval’s comments about moral control in mind, I asked him what the foundation’s policy would be if staffers discovered potentially embarrassing information within composers’ private letters. He answered that the Stiftung doesn’t necessarily encourage composers to turn over their most intimate papers. When they do, composers are allowed to keep certain documents “blocked” from outside eyes for a length of time of their choosing.

In general, it seemed to me, the Paul Sacher Stiftung sees its responsibility to the composer first and to posterity second. Like Sandoval said, this is an ethical decision. Composers think differently about their own legacies than musicologists do. By taking their side, the Stiftung steers the course of research. Dr. Meyer said there are some love letters of Arthur Honegger that could be seen as embarrassing that are still blocked in the collection. This in itself is a moral judgement about extramarital affairs and whether music history has a right to know about them.

Dr. Meyer commented that many of the composers in the Basel collection weren’t exactly appreciated during their lifetimes. To have your documents accepted into the Paul Sacher Stiftung, where manuscripts by Stravinsky, Bartók, and Ligeti are kept, and offered financial remuneration for them, is an honor. The French-Slovenian composer and performer Vinko Globokar told me that his works had been shuttled between storage in Paris, Milan, Munich, and Berlin before finally ending up in Basel. “That’s why I’m very happy to belong to the Sacher Stiftung,” he said.

After talking for about 45 minutes, I felt that Dr. Meyer’s attitude had softened a bit. He gave me a tour of the foundation, showing me the reading rooms, then taking me down another flight of stairs into the cooled safe. He said that he was the kind of person who prefers to read on real paper. A remark Sandoval had made to me—that the whole story is a mix of “bibliophilia, secrecy, money…Umberto Eco would have loved [it]”—came to mind. Due to lack of wall space, Adrian Henri’s famous painting “The Entry of Christ into Liverpool in 1964 (Homage to James Ensor)” hangs in the safe, invisible to the public.

We entered the inner safe where the handwritten scores are kept. He asked me if there was anything in particular I wanted to look at. I said I’d like to see some of Gérard Grisey’s sketches from his “Quatre Chants pour Franchir le Seuil.” Dr. Meyer took them down and placed them on a tabletop. My breath caught a little. I haven’t composed myself in over two years now, and for some reason I was moved to see that Grisey wrote the note head of a high D as a thin slanted line, the same as I’ve always done.

In 1990, Tinguely started planning a memorial artwork to accompany Paul Sacher’s grave. Sacher had requested the work from him, but they disagreed about the direction it was to take. Sacher found Tinguely’s ideas too hectic. Famously, he said, “After death, everything is silent, nothing moves.” Tinguely died before a compromise was ever found. Today, the Paul Sacher Stiftung, for an institution dedicated to music, is a place permeated with a severe kind of quiet.

For living composers who place their works in the Paul Sacher Stiftung’s care, the act of organizing, cataloguing, and selling their materials also involves a delicate mental negotiation with their own mortality. They collect their papers each year, and send them away to be stored forever. “I’m 82 years old. I have two sons, but they are involved with completely other things than music. And when I die, and if [my papers] are lying around in the apartment somewhere, they’ll get lost,” Globokar told me.

I asked him how long his manuscripts would stay in the collection in Basel, thinking that they might later be freed up for further sale or loan to other institutions. He paused a moment. It felt like the first time he had ever thought about it. “Oh man,” he said. “As far as I’ve understood, for eternity. Until they drop the atomic bomb.” ¶