Cate Blanchett isn’t the only conductor in Todd Field’s “Tár” (2022). There is her predecessor at the Berlin Philharmonic, Andris, and the Gilbert Kaplan cipher Eliot (Mark Strong). There are also two assistant conductors: the aspirant Francesca Lentini (Noémie Merlant), who hopes to take the assistant position at the Berlin Phil, and the hapless Sebastian Brix (Allan Corduner), the current assistant whom Lydia wants to remove because he’s part of the ancien régime.

Lydia is initially focalized through Francesca’s eyes, and their scenes together start to reveal the petty tyrannies that will grow in stature as the movie goes on. We are told Francesca is an aspiring conductor, but we never see her make music: She takes care of Lydia’s flights, luggage, and correspondence with record companies, and lingers in the orchestra stalls during rehearsals and recording sessions holding the score. Sebastian is painted as doddering and sycophantic—misaligning his ears around a clarinet solo in Mahler’s Fifth is the excuse Tár needs to give him his marching orders to a lesser orchestra.

The assistant conductors in the film are lackeys and losers. Francesca is understandably embittered about being passed over for the role in the end; Sebastian pleads pitifully with Lydia not to be sent on his way. In “Tár,” being an assistant conductor seems like a dire fate. But that belies the importance of the real job to the final product in the opera house or concert hall, and the possibilities the position offers to young conductors beating a path in concert life.

Recently, I met Nicolò Umberto Foron in a cafe in London’s Barbican Centre. He had just come from the general rehearsal of Mendelssohn’s oratorio “Elijah,” ahead of two performances from the London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus with their Chief Conductor Antonio Pappano. Foron is the LSO’s Assistant Conductor, a position he earned by winning the Donatella Flick LSO Conducting Competition last year. Like most assistants at this level, Foron is an established conductor in his own right (his previous engagements include the Mozarteum Orchester Salzburg, Staatskapelle Weimar, Opéra National de Montpellier and the Tanglewood Festival Orchestra).

But his responsibilities for “Elijah” were as much pastoral as musical, because the two are really indivisible. Ewan Christian, the boy treble who sang the role of the Youth, was in Foron’s charge ahead of the performance; both the assistant conductor and Christian’s teacher were available to help with the warm-up, check over tricky passages, show the young singer the Barbican’s backstage, and generally put him at ease in unfamiliar surroundings. (Going by the reviews, it worked.)

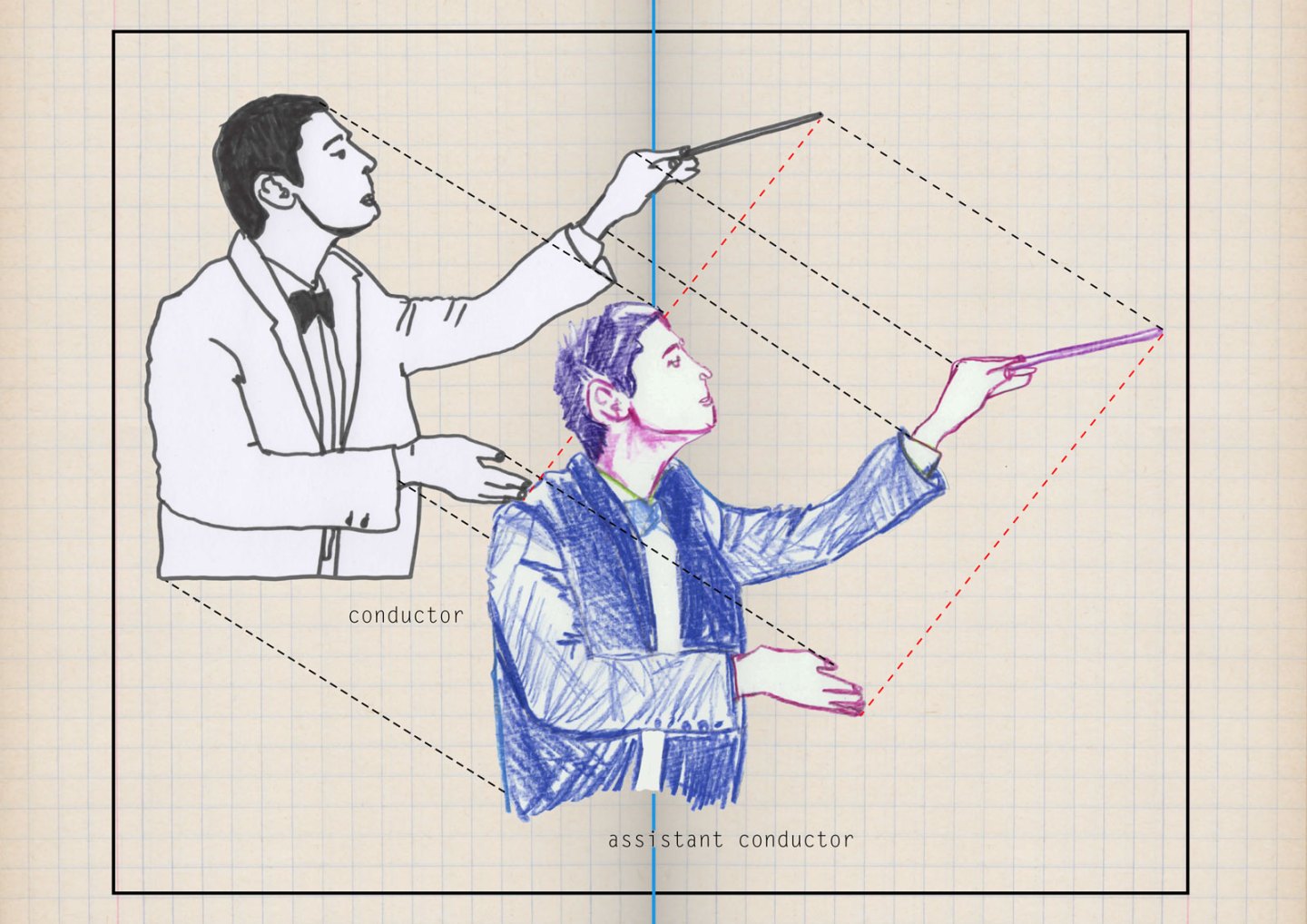

Before our interview, I watched Foron conduct a read-through of Sibelius’s First Symphony with students from the Guildhall School of Music & Drama, bolstered by experienced players from the LSO. In that context, he was a conduit through which the top-flight musicianship of the LSO, which as an assistant he soaks up like a sponge, could pass to the student instrumentalists. But the assistant conductor post is a learning experience for Foron too. “One of the reasons I am still assisting is because I am in something of a transitional phase,” he tells me. “I am now conducting orchestras that are of a significantly greater quality than I have worked with before—here, I can see how musicians of such caliber should be treated, and what might make sense.”

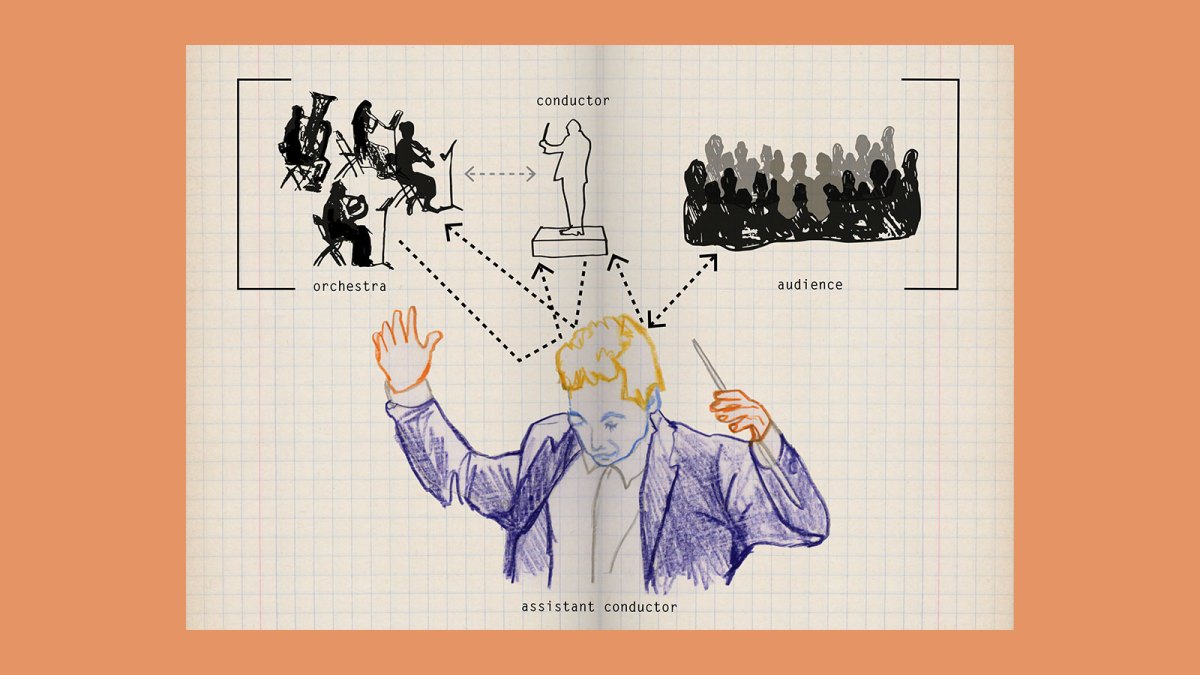

Foron, with his shock of red hair, is energetic and irrepressible, contradicting the idea that an assistant conductor is a passive understudy determinedly waiting for their boss to succumb to the sniffles. He enthuses about his work: “Acoustically the best place is ten meters behind the conductor—people never think about this!” The assistant can see and hear things in the stalls—especially when singers, placed slightly forward of the conductor on the platform, are involved—in a way that the conductor on the podium cannot.

Those ten meters make a world of psychological difference. “When you are in the stress of a rehearsal,” Foron says, “there are so many things that you have to do, a certain level of detachment isn’t possible.” He goes on, “Pierre Boulez said that what he found difficult about conducting was that he could never really be detached—and he had one of the most incredible ears!”

Assistants remind us that conductors aren’t superhuman, despite what the marketing says. According to Foron, Pappano takes a collegial approach to this reality. “Tony is extremely trusting,” Foron says. “He will turn around and ask me, maybe ten times over three hours, for feedback.

“I will stand up and shout ‘Tony,’” Foron tells me. He adds, “He asks for it.”

Accounts of the assisting days of famous conductors tend to intimate gleams of greatness from their days in such a humdrum role. Leonard Bernstein embroidered the account of his appointment as Artur Rodziński’s assistant at the New York Philharmonic with the claim that he, Bernstein, was ordained for the position by God himself. Pappano was assistant to Daniel Barenboim at the Bayreuth Festival in the late 1980s, serving as a rehearsal pianist for the auditions. Barenboim didn’t think much of the soprano, but he wanted to keep the pianist, and off to Bavaria they went.

The mythography of great conductors means that they outgrow the role of the assistant like a snake sloughing off its skin; they are already bursting with an ever-expanding musical imagination. In such accounts, being an assistant is never something vital, enriching, and valued in its own right. One might be mistaken for thinking, to adapt a phrase attributed to John Steinbeck, that assistant conductors are merely temporarily embarrassed music directors.

Beneath the mythmaking are more instructive stories. Nicholas Kenyon’s 2002 book presents a glimpse of Simon Rattle’s early days assisting John Carewe at the Glasgow Schools Symphony Orchestra. “Now I suspect this reinforced a lot he already knew about rehearsing,” Carewe recalled. “We had lots of sectional rehearsals, and we would really pull pieces apart and put them back together again…perhaps this is where Simon saw how you can build up with quite poor players to a high standard.”

Rodziński provided Bernstein with a rigorous training, no divine intervention required. At Rodziński’s “reading rehearsals,” the New York Philharmonic tried out new American scores, often selected and conducted by Bernstein. “Sometimes I had the chance to look at [scores] the night before and sometimes not,” Bernstein said later. “This was tremendous practice, as you can imagine…I knew what it was like to stand on that podium and conduct the Philharmonic.”

Another source of such practice is the opera house, where there are so many moving parts and competing creative priorities that everyone is always assisting someone else. Genevieve Ellis is Assistant Chorus Master at the Royal Opera House in London; her role is to try and preserve the finer details of music and text she crafts with the chorus as scenic rehearsals progress and the production hits the main stage. (There are plenty of musical complications that come from the caprices of blocking and costume.)

She describes an important inflection of the assistant conductor’s psychology: a wholly different relationship to the public and the act of performance. As an assistant conductor, “it is important to keep performing,” she says, “but you have to be prepared to give up your performer self to some extent.” Nevertheless, “you need to keep in the mindset of those who do…for [the chorus] the first night is the first night. You can feel that energy and have to inhabit that curve with them.” Though, for Ellis, it is the first rehearsal with the primary conductor for the opera’s run that feels most like a performance—the culmination of much hard work for an audience of one.

Ellis still performs for the public as well. Assistants are key in bringing off the numerous spectacular uses of offstage musicians in opera: the festive banda at the opening of “Rigoletto,” the distant cantata in Act II of “Tosca.” Particular favorites of Ellis’s include the glowering chorus at the end of “Boris Godunov” and the church scene in Act II of “Peter Grimes”—parts of the operas not seen, but most definitely heard. In 2023, Ellis prepared and conducted the eerie offstage chorus in the UK debut of Kaija Saariaho’s “Innocence.” The singers intone the names of those massacred in the school shooting at the center of the opera. Ellis was responsible for one of the score’s most haunting and distinctive elements.

For Charlotte Corderoy, who is accompanying Barbara Hannigan on a European tour of “The Rake’s Progress” with the Swedish Chamber Orchestra and Swedish Radio Choir, being an assistant conductor means joining the fray. When Hannigan cannot be there, Corduroy must act as a “mirror” for her on the podium. She is working with Hannigan as part of the Equilibrium Young Artists scheme, a mentoring opportunity for musicians in the first stages of their professional careers. The program guarantees someone like Corderoy proper billing as assistant conductor, a share of the limelight, and a rounded experience of participation in every stage of the creative and dramatic realization of project. Assistant conductors always have plenty to do in opera, but in Josie Daxter’s semi-staging Corderoy steps onto the podium as Hannigan moves aside and “becomes the bread machine.” (In one sequence Tom Rakewell dreams into existence a miraculous contraption that turns rocks into loaves.)

Corderoy is also Assistant Conductor at the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, where she works closely with Chief Conductor Kazuki Yamada. “90 percent of the job for me is balance stuff,” she says, meaning she spends a lot of time taking notes in the auditorium. But the changing character of contemporary orchestral programming and musical dramaturgy is giving Corderoy and others much more to do than ever before. A recent CBSO program paired Beethoven’s Eroica with Strauss’s “Don Quixote” and brought choreography, lighting and video into the concert. “Suddenly you’re coordinating with videographers; animateurs might need to know where an orchestral cue is,” Corderoy says. “In one section, a fugue, we had the musicians standing for their entries…so I had to act as a go-between for the musicians and choreographer.”

In “Tár,” the assistant conductors see Lydia for what she is. When Francesca is blocked by Lydia from taking the vacant post because her loyalties are in doubt, the incident incites Lydia’s ultimate downfall. When the conductor goes to Francesca’s apartment to confront her, all she discovers is the typescript of her book, where “Tár” is scribbled over and replaced with its inversion: Rat. Things look different when you’re not on the concert platform but watching from the stalls.

The assistant conductors I spoke with didn’t share any plots to bring down their colleagues. But Corderoy captured the special quality of attention essential to the role. “These are things that can’t be learned at music college,” she tells me. “You have to understand the dynamic of the rehearsal room firsthand, the dynamics of backstage, what happens in the break, when to have those conversations and when not.” Ear training takes many forms; balance is social and temperamental as well sonic. These skills should matter to all musicians, but the assistant conductor is in an especially strong position to fine-tune them.

Being an assistant conductor calls for open-mindedness, patience, a willingness to listen and look before leaping, lack of ego, and a sleuth’s eye and ear for detail. Some of these qualities are at odds with traditional pictures of musical leadership, where a maestro motivates or subordinates his musicians through sheer force of will and swagger. (Beat first, ask questions later.) This is no longer a viable way of working in a profession whose values are shifting. The conductors of tomorrow might best be modeled on the assistants of today. ¶

Update, 2/26/2024: A previous version of this article presented Foron’s quote, “Tony is extremely trusting. He will turn around and ask me, maybe ten times over three hours, for feedback. I will stand up and shout ‘Tony.’ He asks for it,” as a single thought. The statement was actually made at two different points in the interview; the article has been updated to reflect this. VAN regrets the error.