Have you heard a concert, seen a play, or watched an opera, any time in the last 30 years? (Or read VAN?) If so, you’ve probably come across a photograph by Monika Rittershaus. She’s one of Europe’s best and most in-demand theater photographers, working with leading houses, conductors and directors. Rittershaus is the first choice—and often the only choice—for artists like Daniel Barenboin, Simon Rattle, Christof Loy, Barrie Kosky, Romeo Castellucci, Claus Guth and Mariame Clément. She’s also the main photographer for the Berlin Philharmonic, accompanying the orchestra both at home and on tour.

It’s easy to spot a Rittershaus photograph, especially if you’ve seen the performance she shot. Her images are never of the most obvious, forward, blunt, or usual scenes. Instead, she finds and captures fleeting moments in which the essence of a production emerges. “Monika understands the time and space of the theater like no other theater photographer I know,” Kosky writes in his introduction to The Scene and the Unseen, a book collecting 15 years of Rittershaus’s opera photography. “Her photos are no mere reproductions of someone else’s artwork; they are artworks themselves,” he adds.

I met Rittershaus in December in a Berlin café. She had just come from Amsterdam (“Turandot”) and Zurich (“Eliogabalo”), and was preparing to work in Berlin’s Philharmonie before heading on to Geneva (“Maria Stuart”).

VAN: Do you always travel this much?

Monika Rittershaus: It’s been extreme lately. In September I photographed the “Ring” cycle at the Staatsoper Berlin, so I was here for a bit, but since then I’ve been on the road pretty much all the time.

Why? Because you feel like working? Or because there are a lot of interesting opportunities right now?

Both. When a house or one of the directorial teams I enjoy working with asks, it’s hard to say no if there’s any way of figuring it out.

Do you need to reach out to clients anymore, or do they all come to you?

I’ve never really needed to reach out to clients, which I’m grateful for. Sometimes I hear about an interesting production somewhere, put on by a directorial team I trust, that would conflict with another offer. Then I ask the director: “Are you counting on me?” Normally it’s first come, first serve, but if the people I work with regularly ask, I try to make it happen.

Who decides on whether you get hired, the opera house or the director?

Some opera houses and theaters offer me productions. Then there are directorial teams that tell the houses they’d like to work with me. But there are also places where that doesn’t work, say Italy or England, where they have their own photographers at each house. On occasion, a director will hire me on their own dime. Claus Guth did that for his “Salome” at the Bolshoi in Moscow last year. But so far, the house has always ended up using the pictures anyway once they’ve seen them. When you work with a person for such a long time, of course you get different results.

Why do you keep working with the same directorial teams?

It’s important for me to feel a sense of mutual trust, to have the feeling that I’m wanted, and not to feel like I’ve been forced on them. It’s not like I’m the only theater photographer.

How long do you usually spend on the set of a production?

I’m old school: I don’t start taking pictures right away. First, I want to see something—one, two, three rehearsals, if at all possible, before I even start taking photos. That’s very important to me. If that’s not possible, say because a rehearsal had to be canceled, then I make sure to gather lots of material, which I then use to prepare.

Like what?

Notes from conceptual meetings, interviews for the program book, costume photos, sketch books, interviews with the directorial team…

In how many rehearsals are you allowed to photograph?

In opera, usually three. A few more in the theater.

Do you ever show up to a rehearsal and think, “I can’t find a way into this production”?

It happens, but under no circumstances should anyone be able to tell. I think I manage that because I’m not judging what I’m seeing. But afterwards, I do think about whether I should work with the same team again.

What about productions that you liked, but were difficult to photograph?

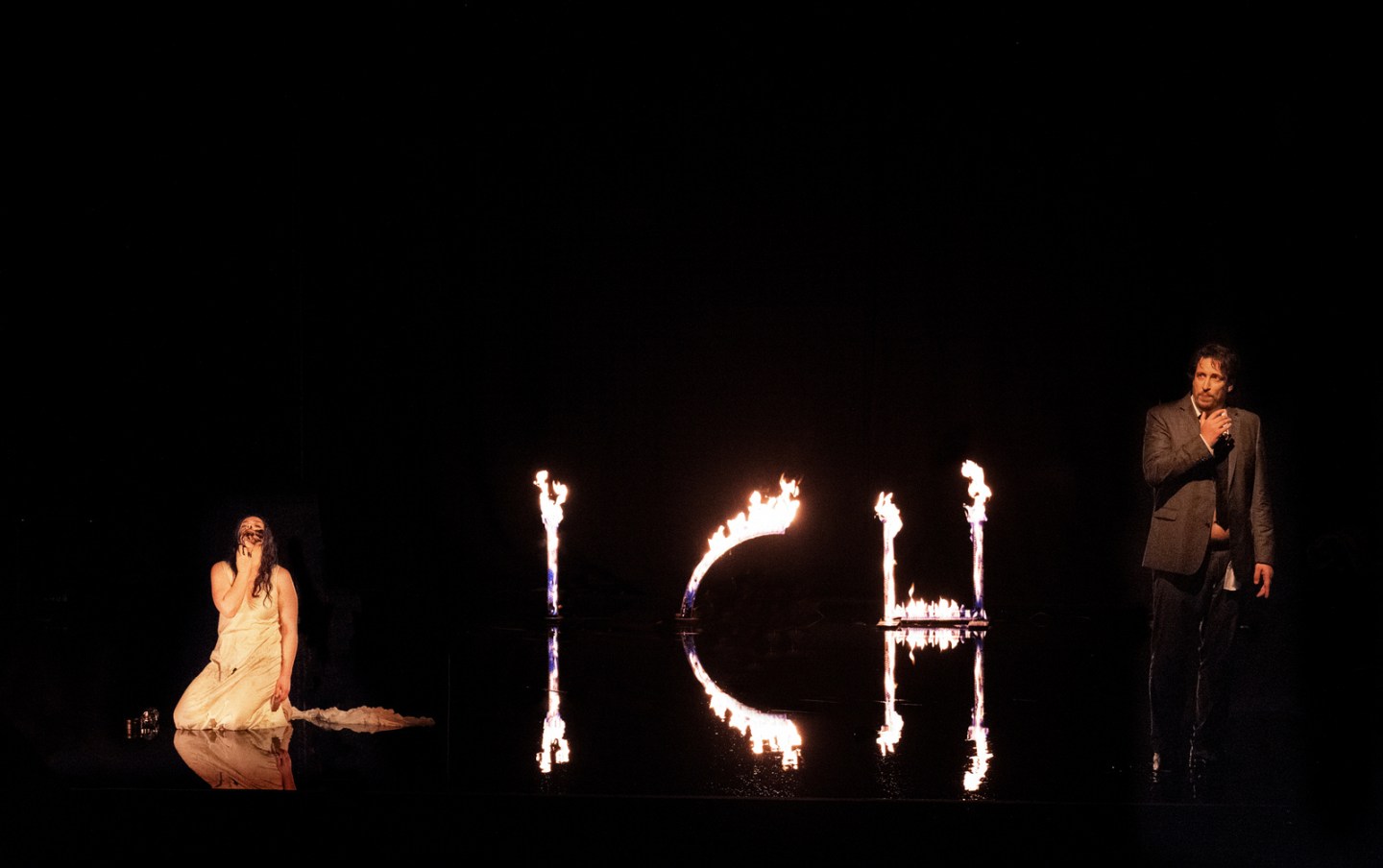

“Bluebeard’s Castle” in Salzburg [in the summer of 2022] was unbelievably difficult, technically: a dark, almost empty room, two singers, symbols rising from water and fire. I walked through the whole building, the Felsenreitschule, and tried to find angles where I could see the reflection of the fire in the water. At one point this created the word “ICH” [“I”]. Romeo Castellucci told me in advance that taking pictures might be hard, so I went to Salzburg a few days early, watched rehearsals, and tried to figure out how I could translate this incredible atmosphere into images. I want what’s special about a production to come through.

When you’re walking around in the hall looking for the right angle, are you allowed to go anywhere you want?

In the houses where I work regularly, people know me now. They know I don’t do stupid stuff. I don’t wear heels. I wear black. I don’t suddenly block the monitor or knock something over. I’ve been doing it too long for that to happen. During the COVID-19 pandemic, I started photographing empty theaters. Doing that, I met a lot of people I hadn’t met before, the people responsible for making the staging run smoothly. They’re fantastic, and now I know my way around the houses even better. Sometimes, I have to be accompanied, for security reasons, or I have to hang the camera around my neck, which I don’t normally do. But take the technical directors in Frankfurt or Salzburg: They’re creatures of the theater, they want me to get the best possible shot too. That’s the main thing. You can do your job by the book, or you can allow a person to create something special.

At the beginning, were you more worried about moving around during the rehearsal and “disturbing” it?

Yes, definitely. At the very beginning, I always took my shoes off. Going out from the darkness—same as giving this interview—takes me out of my comfort zone. I really like being invisible. But when I feel that there’s a shot if I go here, and it would look good, then it makes me nervous not to do it. That can get on people’s nerves. But I’m like, Leave me alone, I’ll be careful, it’s not dangerous, I’m not stupid, I’m not going to fall down there.

Have there been complaints about you from artists during rehearsals?

I very rarely go on stage, because I find it too close. Anway, most people on stage are so absorbed by what they’re doing they don’t even realize I’m there. At one point [Austrian actor] Klaus Maria Brandauer was rehearsing Peter Stein’s [11-hour Schiller marathon] “Wallenstein,” and he said, “From now on, no more clicking.” But it was just the two of us, and anyway cameras these days are much quieter.

Do you ever read reviews of a production that you’ve photographed and think, I understood this, but not too many other people did?

Sure, sometimes you feel like you were on a different planet. I don’t even know if I always see what the directorial team is going for. But as long as I find something to connect with, whatever it is—a voice, an element of the set that touches me—I’m in the piece, and then I can try to unfurl it. It’s not my job to judge it. I look at it, and it’s material in the best way.

How well do you know the works that you photograph? Do you know their grand pauses and pianissimo spots by heart, so that your camera doesn’t click into the quiet?

I used to be even more extreme about it—before soundless cameras—because I was so anxious about making a clicking sound during a grand pause. Violins hide the clicking sound better than low instruments because the click is fairly high in pitch. That’s the kind of thing you learn. At one point I had to take pictures of a recording of the complete Beethoven Piano Sonatas, before soundless cameras existed. That was really hard. I was sitting on a stool in a box at the Staatsoper, I put the camera under a covering, hid that beneath my jacket… I had to know the sonatas very precisely.

What’s the difference between taking photos in the theater and at the opera?

In opera, you and your camera can “hurt” the singers. I really dislike photos with singers’ mouths wide open. If it’s an experience of an extreme emotion, like a scream, then it’s great, but you shouldn’t see the physical exertion of singing. It’s another reason it’s good I know the pieces well, because I know when a vowel is coming. I know some singers pretty well; I know how wide their mouths open when they sing certain vowel sounds. Singers have to be in a specific state to produce and develop the sound, so I try not to take the picture at the most difficult moment for them. Now there are lots of singers who are good actors too, but the moment of singing doesn’t go away: they have to stay conscious of it. Singers can’t give themselves up completely the way actors can. And they also have to sing to the front, so they carry over the orchestra and stay in touch with the conductor. If I’m taking a picture of an intense love scene, but you can see that one of the singers is looking past their partner toward the monitor—that doesn’t work. I’m very careful about that.

You have a lot of responsibility: to the singers, to the production, to the directorial team, and to the work itself. Has that responsibility ever felt overwhelming?

Definitely, I agree that it’s a big responsibility, and I’m not sure it’s always possible to live up to it. I often think that I could have done better and portrayed the visual realization of a production more accurately. Respect, responsibility, and precision are unbelievably important to me. When I was a student, one of my professors told me, “The most important thing you have to keep in mind as a photographer is to uphold the dignity of the subject.” There’s something extremely beautiful about that. I try to be loving and careful with it. It never feels routine, it’s always stressful. The longer I work and the more important the houses, the teams, and all the participants become to me, the more I need to justify why I should be allowed to be there—especially if there was disagreement about whether I should be hired in the first place.

Then there’s the balancing act between each participants’ priorities. A singer wants to look good, the house wants to showcase the production or bring media attention, the directorial team wants its concept represented clearly, the set designers want to see their work… and then there’s you, who needs a good photo. Do you end up with compromise shots, or do you take so many pictures that each group gets photos that satisfy them?

It’s not usually discussed openly, but I’m aware of these priorities at all times. I have to make sure I’m not just fulfilling wishes. I’m very much a theater person, I take my pictures from the inside out; my goal is to live up to the theatrical model, but at the same time, I’m a photographer and I want a good picture. One of the things I’m least interested in is a famous person who wants a photo of themselves looking like a star…

But sometimes you have to do it anyway?

I try not to. Instead, I try to compose images, to show the singers in the context of the production, and to show what makes the production unique. I’m not interested in close-ups.

It’s not always easy to satisfy everyone. Some singers have the contractual right to decide on the final selection of images with me, and their ideas don’t always gel with mine or with those of the directorial team. Because of that, you sometimes need to think carefully about who gets to see what first: Does the directorial team see everything and the singers just the final selection approved by the team, or vice versa?

Is it always different?

Yes, sometimes it’s a psychological question, you have to consider who you show the pictures to first. [Smiles.]

But it’s not like you can only take one picture. Do you ever say, “I’ll bite the bullet now and take a picture of the famous singer posing like a star”?

I try not to. First, I try to gather the material and find something that works for everyone. If it becomes clear that that’ll be hard, I will sometimes choose pictures I’m not as happy with—maybe they don’t have the same power or message behind them as others—so that they get approved. It’s a challenge.

Do you look at which shots photo editors at newspapers and magazines choose?

Yes.

Do you often find yourself thinking that they chose the most “obvious” picture, rather than the best one?

Yes, it’s pretty shocking. [Laughs.]

You’ve been using the phrase “directorial teams.” In the media, the focus is usually on the individual director, the singers, the conductor. But in your pictures, you allow other things to come through: the lighting, the set, the props, the costumes… Do you get frustrated when those aspects of an opera production are ignored?

Yes, for me every detail is so important. The costumes get underestimated all the time, for example. I can see right away when someone doesn’t feel comfortable in their costume or when it doesn’t fit right. I started working with Achim Freyer, who taught me to pay attention to every single action and every single detail on the stage. It’s not only the protagonists who matter. Often what’s going on at the edge of the action is more telling.

When you started your career, the internet didn’t exist yet. Now everything is digital, and society is so image-focused. How has that changed your work?

It definitely hasn’t gotten easier. People expect everything faster, and for the editing to be included. It used to be this big tragedy if something wasn’t ready [to be photographed] by the dress rehearsals; now it’s like, “You can figure it out with Photoshop, right?” At first I resisted digital photography, because I loved working in the darkroom. When I’m working in a place like Salzburg, where there’s so much bustle, I liked to be able to go back into the darkness and be alone—I liked those two extremes. There were moments of calm. It also took time for the film to dry. Now, sometimes I’m asked to show my pictures right after the rehearsal. I completely refuse, though. I’d rather pull an all-nighter and then show what I want to show the next morning, but not right away.

Has the fact that it’s now easy to take hundreds, even thousands of photos and then discard the ones you don’t need changed your work?

Deep now, I’m still an analog photographer. I don’t shoot wildly. Sometimes I’m stunned by how much clicking happens at a public photo rehearsal. I used to work with reversal film, which needs time to sit, there’s no shortcut with it. I don’t just start taking photos, thinking, I’ll be able to edit them and get the right framing later on. I internalized the analog way of working. I also don’t look at the photos in the camera, I just check the lighting. Sometimes I see people take the picture and immediately look at the screen to check, but that would bring me out of the flow completely.

What kind of image editing are you willing to do? When does it start to feel dishonest?

The high levels of contrast on stage are hard for the camera. If you photograph in RAW mode, you can even out the contrasts and color shifts that arise through the use of video, for example, during editing. A black-and-white video projection will often create a line of cyan through the camera. So I’m not changing the image, but trying to make it look like the staging. If there are mistakes during the early rehearsals, like a rope hanging somewhere that’s not supposed to be there, or markings for the rotating stage, then I’ll take those out. But I would never switch heads, say.

Do directors ask you for advice?

I’m definitely sometimes asked what I see, and then it becomes clear in the photos if what they are trying to convey is actually coming across. It’s a fantastic kind of dialogue. If I’m having trouble with the realization of a scene, some people ask themselves if maybe something is wrong, if that explains why I can’t photograph it. Many others say: When I arrive, that means things are getting serious. They know that it’s almost finished, because the first person from outside is coming to look at it.

Do you have a favorite production?

One of the most interesting productions I’ve ever photographed was Romeo Castellucci’s “Résurrection” with Mahler’s Symphony No. 2 in Aix-en-Provence. It was such a special night of theater: courageous, relevant, elementary, and important for our time. The location, the Stadium de Vitrolles, this chunk of concrete in the middle of nowhere… At first, all you see on stage is mud, and then a horse enters… What it takes to even come up with such an idea, and then to realize it with such rigor! When he came up with the concept, the war [in Ukraine] hadn’t even started yet, but the way it became so relevant all of a sudden, the dichotomy between this unbelievably beautiful music and these acts of unspeakable cruelty—it had such stature. The first time I saw it, it completely shook me. I had no idea how it would work: How could you show all this while preserving human dignity? At first, I had to take pictures simply to chronicle what was happening, I thought: I need to put something between me and my emotions. That was the camera. Then I realized that wouldn’t work. You can’t show it, you have to imply it. You have to show the pain, but you can’t expose it completely by putting it on show.

Do you watch the productions that you photograph?

Rarely. I’m often not there anymore. And I’m extremely empathetic. When I feel like someone isn’t appreciating or understanding what’s going on, then that messes me up. I can’t handle it when someone looks at their watch or isn’t concentrating, or when a moment happens that I’m particularly fond of, and I realize that it isn’t working.

How about productions you’ve never really gotten?

I wouldn’t say there are ones I’ve never gotten, but there are often completely different takes. The “Marriage of Figaro” in Salzburg in 2006, directed by Claus Guth, conducted by Nikolaus Harnoncourt, with Anna Netrebko as Susanna and Christine Schäfer as Cherubino, is definitely one of my favorite productions. It was the opening of the Haus für Mozart and was shown live on prime-time TV: An uncut “Figaro” by Harnoncourt, lasting something like four and a half hours. I think it was a challenge for the audience in Salzburg. But it was such a sensitive production, almost like a Bergman film: not funny, but deep and precise and beautiful, created by teamwork. I was in the audience, and the premiere was simply not the same as the rehearsals. There was a certain tension, it started late, it was crazy hot, and the audience wasn’t just opera lovers, I’m sure… I felt so bad.

Your website has pictures that aren’t from the opera house, the theater, or the concert hall: panoramas of natural and urban landscapes. Do you ever feel like a break from theater photography?

That’s my side project; I don’t want any jobs in that area. In my innermost self, I’m a photographer, meaning wherever I go, I always have my camera with me. The panoramas you mention are analog and always have the black border from the negatives, meaning they’re exactly as I photographed them. That’s how I got started, and I still want to work with the same precision. There’s something cleansing about being out with my camera, because I have to concentrate on what’s at hand. It’s really good for my head. I’d like to keep it as my side project.

But if a major magazine came and said, “We want to do a photo spread on abandoned factory buildings in the Rust Belt of the U.S., interested?”…

I mean, I’d be interested. [Laughs.] But I’m very happy with my theater photography. I love the theater and the opera, I’m such a nerd. And I’m so lucky that I don’t have requirements to fulfill. Nobody comes up to me before I start and says, “Now do this or that.” Sometimes I ask, “Is there something that’s especially important to you?” But most people answer, “No, we’re curious what you see.” And that’s wonderful. The way it’s so often done these days—the camera attached to the computer, with the art direction team sitting there giving the thumbs up or the thumbs down—I couldn’t work that way. I need freedom in order to work. ¶