In the days following Leon Fleisher’s death, at the age of 92, I’ve found myself listening to his Bach. They’re few compared to the pianist’s more notable repertoire of Beethoven and Brahms, but two can be found on his 2004 album, “Two Hands.”

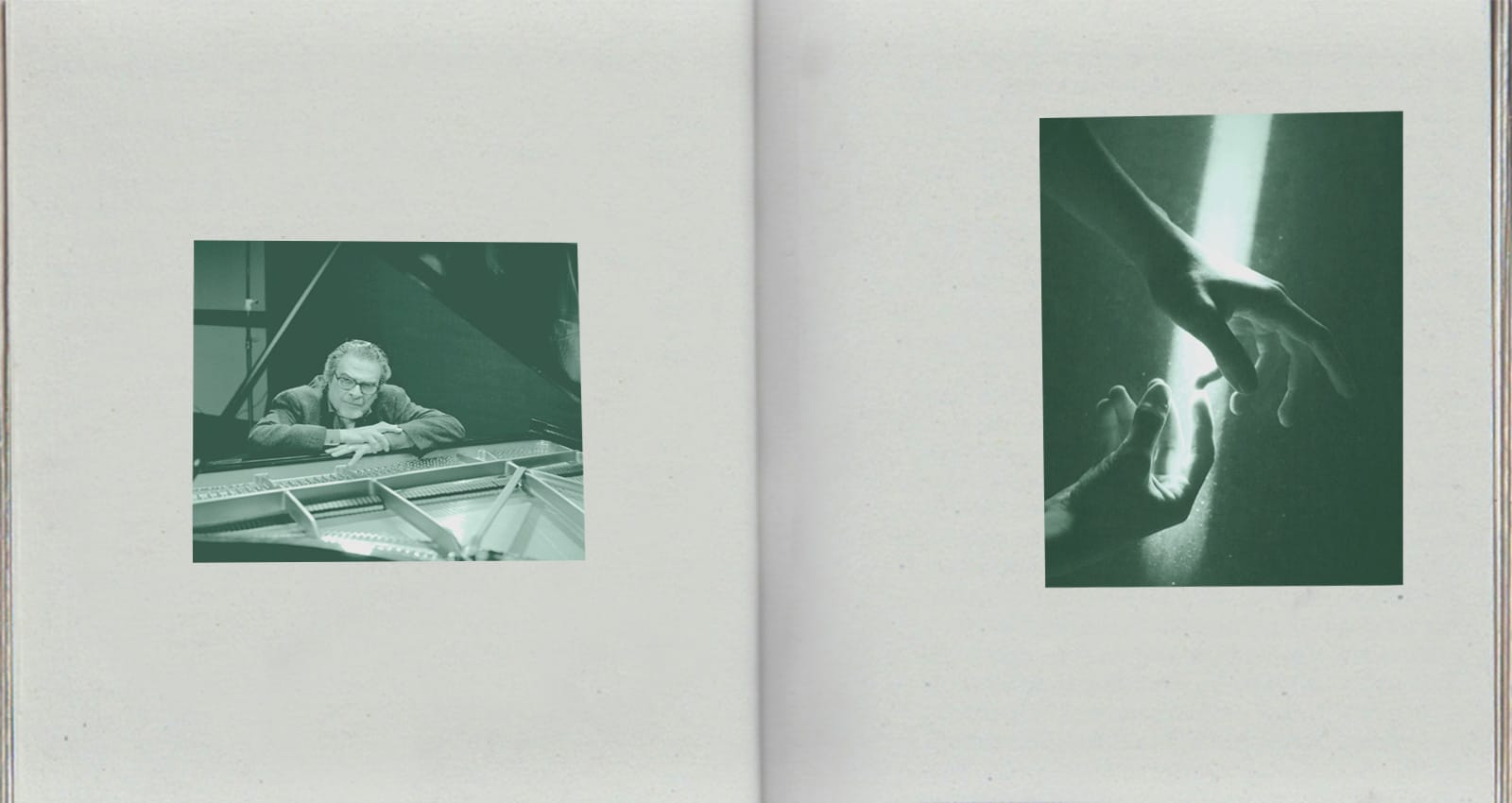

It was a recording that was also something of a rebirth (how apt that both those words share the same Latin root, “to go back to the original source”). After nearly 40 years, it was proof that Fleisher, who lost the use of two fingers in his right hand at the age of 36, was able to play again.

“The Greek myths are full of tales of heroes cut down in the arrogance of their prime, taught humility by a blow from the gods,” Fleisher wrote in his 2011 memoir (coauthored with Anne Midgette), My Nine Lives. “When the gods want to get you, they know right where to strike: the place it will hurt the most.”

In the mid-1960s, Fleisher, who had already been playing professionally for nearly three decades, thought he would never play again. The obituaries that have proliferated this week in the wake of Fleisher’s death on Sunday tend to lead with his triumph in spite of tragedy. They focus on his narrative of turning to pedagogy and conducting, while continuing to chase down medical advances, eventually finding success with the alternative therapeutic technique known as Rolfing combined with an early adoption of Botox injections. Fleisher’s return to the keyboard (with both hands) has become its own canon, its own mythos. Die Welt referred to him this week as “the left-hand of God.” Reviewing “Two Hands” upon its release, Gramophone said the comeback “verges on the unbelievable.”

Fleisher didn’t rely on the same mythologizing in his memoir. “Inwardly, I railed against my situation; outwardly, I hid from it, turning away from friends and family, trying to prove however I could that I was still vital,” he wrote. He grew out his hair, adopted a bead, and began “tooling around on a Vespa.” In the mid-60s, he had reached his own personal crisis as America reached a national crisis. For a time, even considered suicide.

Instead, Fleisher—whose formative years as a child and as a musician were spent studying under Artur Schnabel (making Fleisher one handshake away from Brahms) turned to teaching. In turn, his student Dina Koston (a composer who had studied with Nadia Boulanger and spent a summer in the experimental hot springs of Darmstadt), turned him on to the idea of conducting, specifically contemporary works. For a musician steeped in the German and Austrian Romantics, this was a shift, but Koston felt Fleisher’s focus on tempo and rhythm would be an asset for the intricate, thorny scores of Ligeti, Boulez, Nono, and Dallapiccola.

Koston’s connections in the leftist activist circles of the 1960s helped the pair to launch the Theater Chamber Players, which began in a small theater in the Georgetown neighborhood of Washington, D.C. Mozart mingled with Birtwistle. Performances could involve classical cadenzas followed by the cathartic smash of a tray of glassware. “Beethoven it wasn’t,” Fleisher recalled of the latter (part of a score by Ligeti). “But it was exciting as hell.”

The excitement and the urgency of these works, steeped in an era of revolution, must have spoken to the parts of Fleisher’s psyche that were still working to triage the spiritual trauma of his career setback, just as he himself sought out every available option to treat the physical trauma (in either medium, a Vespa is a poor tourniquet). But Fleisher’s isn’t the story of a traditionalist who then abandons the canon that shaped his youth. It’s a spectrum in lieu of a binary. “Turning so much thought and energy in new musical directions had the effect of cleaning out my ears,” he wrote. “When I turned back to music I knew well or a student brought me a familiar piece, it seemed newer and fresher as well.” Juxtaposition led to illumination.

And experimentation, as it so often does, mellows into gentrification. The Theater Chamber Players moved from their tiny studio on O Street into the Smithsonian, followed by the Kennedy Center. Pierre Boulez went from anti-establishment to being the establishment with his time at the helm of the New York Philharmonic in the 1970s (his name has been lent to a concert hall in Berlin, designed by fellow former radical Frank Gehry).

Part of why the juxtaposition worked for Fleisher (intentionality versus tokenism) was thanks to his early studies with Schnabel. His mentor at the keyboard was famously wary of showmanship. Speaking in a master class recorded this January for the app Tonebase, Fleisher observed that Schnabel was “so patently not interested in that kind of glamorized, societeized career that gave rise to [Vladimir] Horowitz.” Instead, Schnabel honed in on finding truth beyond the charisma or cult of personality. His interest in playing music that was better than any of its interpreters was Rilke-esque; truth was in the question versus the answer.

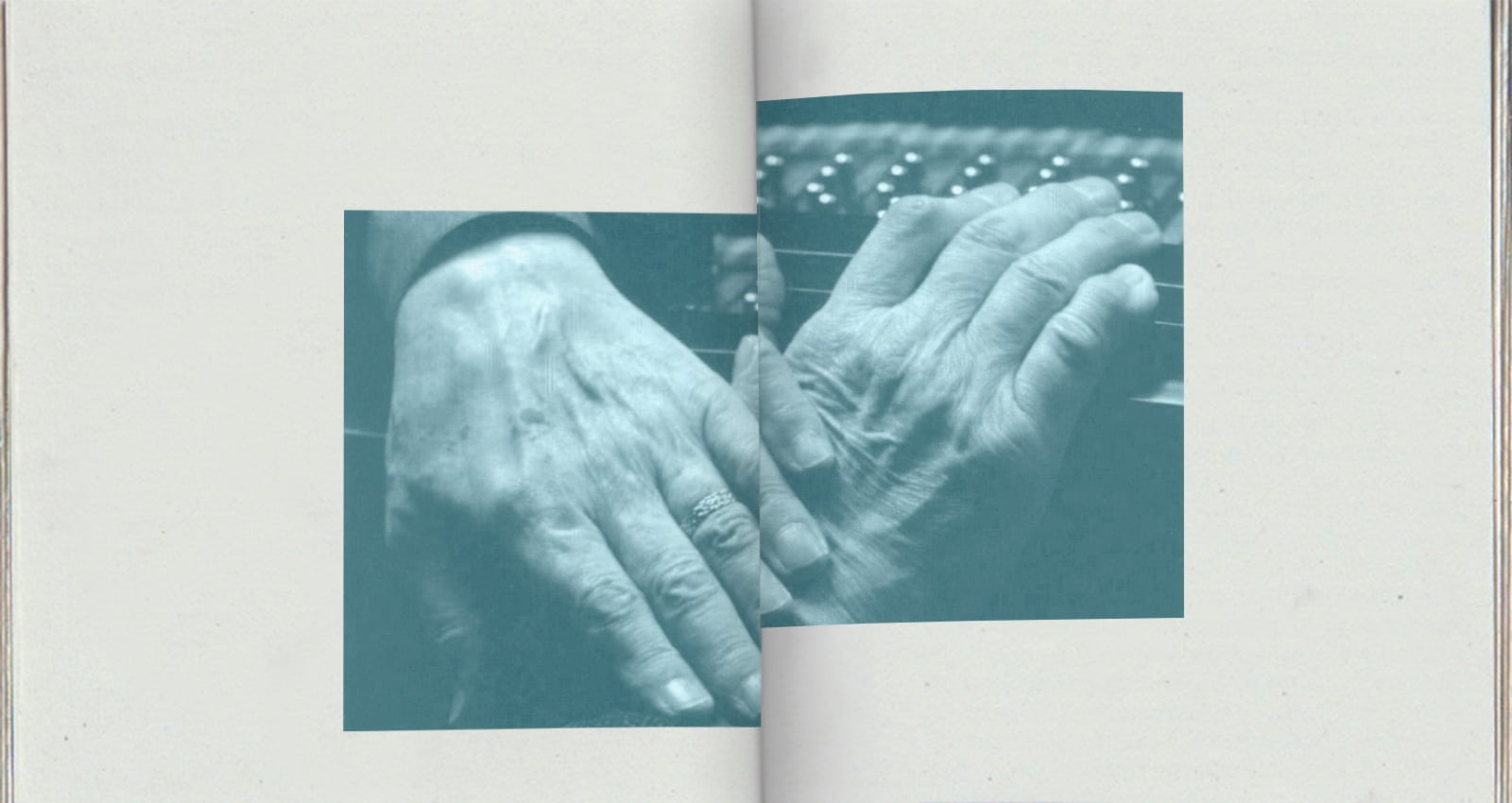

The truth of Fleisher is in his own questions, his dogged pursuit of answers (from spiritual healers to experimental treatments) is more interesting than the answer itself. You can’t help but listen to “Two Hands” (the title itself suggestive of juxtaposition; a distant cousin of “on the one hand…”) without hearing simply the music. It’s about the truth behind it. To quote Fleisher, “You will never get the answer until you listen to what you do, and ‘til you really hear the music and make a decision, make a choice for what you want to hear, for what you think the music is saying. It’s all so much more in your hands than you think.”

“You will never get the answer until you listen to what you do.”

Which brings us back to Bach. “Sheep May Safely Graze” is the second track on “Two Hands,” a chaser to the other popular favorite, “Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring.” They’re simple pieces, easy listening—not the sort of opening salvos one would expect for a hero’s triumphant return. It’s hard not to listen to “Sheep” without some sense of guilty pleasure, an experienced heightened for me by the fact that my first encounters with both “Sheep” and “Jesu” were from a series of recordings made in the late 1980s by the London Symphony Orchestra for (of all places) Victoria’s Secret.

But within these works is something vital and primordial. “Sheep May Safely Graze” was woven into Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck’s 2018 film, Never Look Away. The piece itself is played early on in the film by Elisabeth, the aunt of the Gerhard-Richter–inspired Kurt, as she suffers a schizophrenic breakdown. As she’s soon dragged away by the Nazis (to be involuntarily committed and later executed), the young Kurt averts his Gaze. In a moment of lucidity, Elisabeth tells him to “never look away,” because “everything that is true holds beauty in it.”

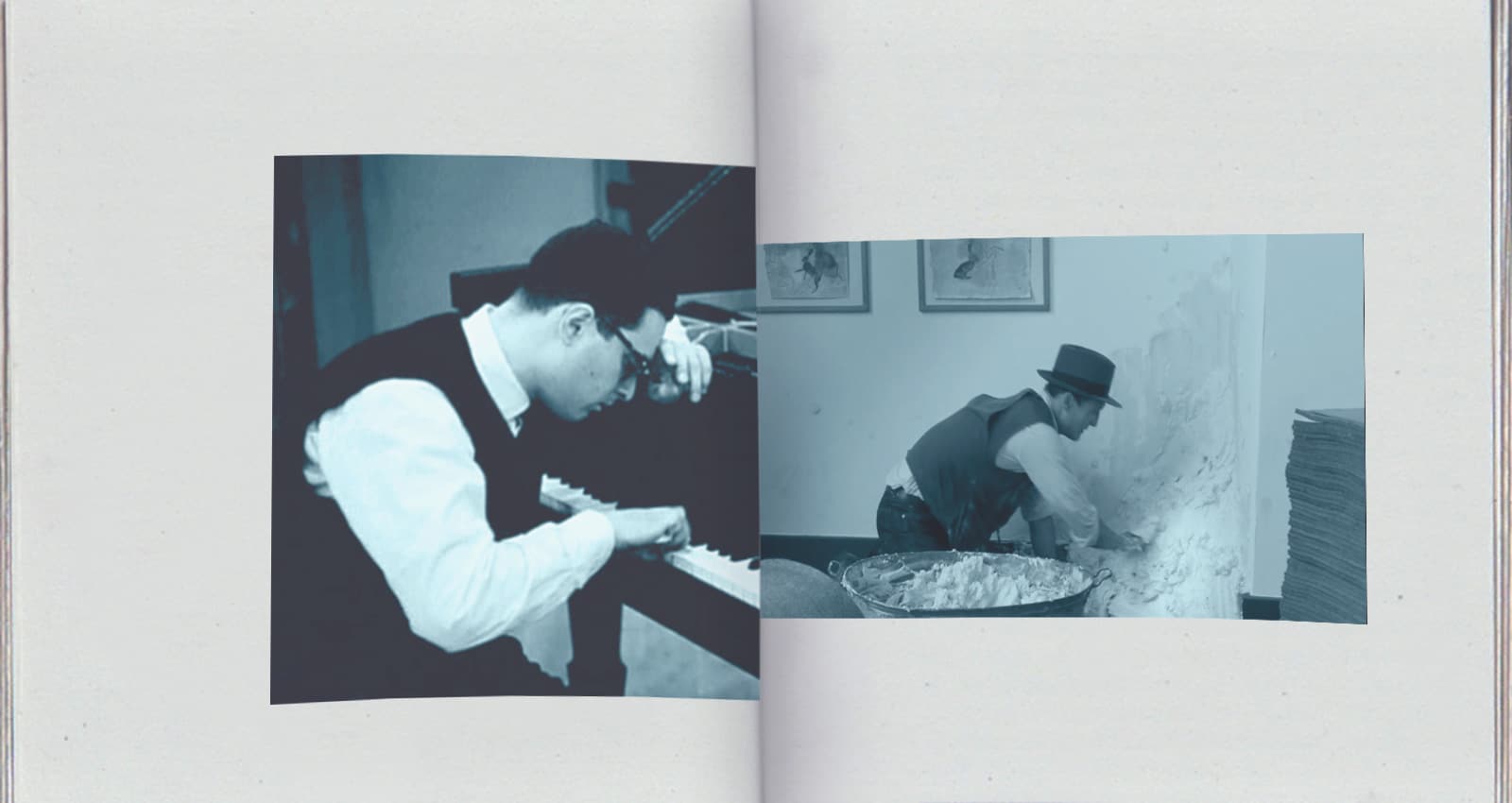

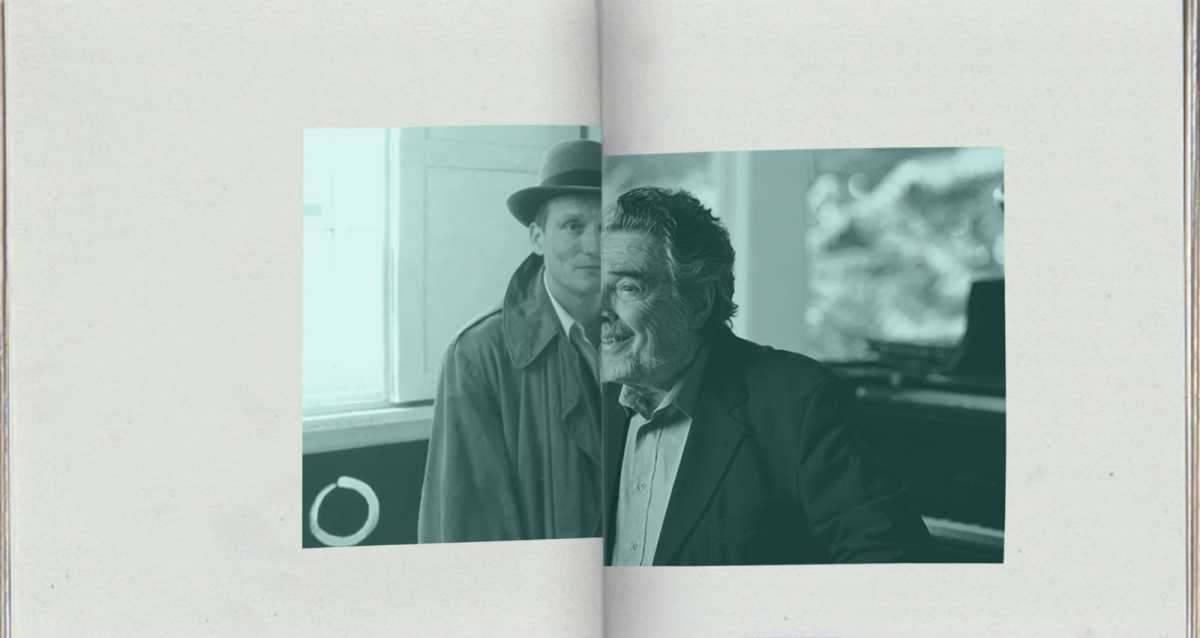

The score for Never Look Away is written by another Richter—Max (who shared a teacher with Dina Koston in Luciano Berio). Richter layers in the familiar chords of Bach throughout the score as Kurt faces his own setbacks and illuminations while developing as a painter. At 26, Kurt and his wife flee East Germany for the West, just before the Berlin Wall effectively sealed off the border between the two countries. Relocating to Düsseldorf and enrolling in the city’s Kunstakademie, he’s thrust in the world of experimental art and challenged to find his own voice while unlearning the Soviet Realist style he learned in Saxony as a matter of course. His professor is a Schnabel-like figure, the enigmatic Antonius van Verten, a man who never removes his hat and an artist who only works with fat and felt. (Many of van Verten’s students find that both traits are pretensions.)

In a rare visit to Kurt’s studio, van Verten looks over his student’s stylistic dalliances. He’s tried many of the convention-less conventions used by his classmates (slashing canvases, Pollock-like drips, monochrome), and the results of those experiments are scattered around his studio. The hodge-podge is all showmanship, no truth.

Van Verten, meanwhile, doesn’t say anything about the pieces. Instead, he tells Kurt that he was in the Luftwaffe during the war and was shot down over Crimea. He would have died had he not been discovered by a group of Tatar nomads who bring him back to their home. There, he’s wrapped in felt blankets and his burns from the crash are treated with grease. A woman softly sings as she tenderly massages his head. Until that point, van Veretn’s life had been uneventful, uncomplicated. His life after that time was very much the same.

“If I ask myself what I truly know, what I’ve truly experienced in life, what I can claim without lying,” van Verten tells Kurt, against the insistent notes of Bach, “It’s the grease on my skin. The home that is fat and felt.… Those I perceived and understood so thoroughly, like Descartes understood that he existed. ‘I think therefore I am.’ He questioned everything. Everything. Everything could be an illusion, a trick, his imagination. But then he realized that something was thinking those thoughts. So consequently, something must exist. And that something he decided to call ‘myself.’”

Who is Kurt? What is Kurt? At this point, van Verten can’t tell, even though he knows that something is there. “This,” he says, gesturing to the jumble of work around him, “is not you.” As he turns to leave the studio, he pauses to lift his hat and bow in farewell. In doing so, Kurt (and we the audience) sees the vibrant scars of van Verten’s war wounds. The mystery of the hat is revealed, the truth of his story confirmed. It’s a beautiful, intimate moment told at a perfect tempo.

I think of this moment while listening to Fleisher and his recording of what is one of the most over-recorded Bach works. Rather than perfunctory, it’s equally honest and revelatory. Much of what I love about Fleisher, and Bach, is writ small in these five minutes. In them is something of Fleisher’s own version fat and felt, more telling of who he is than the whole of his autobiography.

In 2020, we’ve circled back into a level of political unrest and social upheaval that mirrors the turbulence of the mid-60s, as a society on the whole and as a community of people who make and absorb music. Truths are being revealed in whisper networks, whispers are becoming more insistent roars. Even turning to Bach in 2020, whose works offer us glimpses of both unalloyed humanity and unsettling antisemitism, seems superficial and problematic.

But both can be true. In his review for Never Look Away, Antony Lane wrote that “appearances are not merely deceptive but doomed to be incomplete; they dare us to pierce them, as best we can, and to puzzle over the truths that they encrypt.” Fleisher’s legacy reminds us that we can slash canvases and smash trays of glasses and find truth in these actions. We can also find truth in the shadowlands of history and tradition. We can find even more when we look at both at the same time, finding the illumination of juxtaposition.

In Fleisher’s absence, we’re left to continue puzzling. We’re also challenged to continue listening. ¶

Comments are closed.