In four separate, darkened rooms sit five performers. One prepared piano, a Hardanger fiddle, clarinet, and guitar with electronics. It’s a chamber concert for wanderers, with each instrument piped into the other rooms via wires and speakers. The format has been exploded, and while the fragmentary sounds of Stephen Mediell’s “Metrics,” which they’re performing, are nice to listen to as I wander from room to room, it’s their resultant constellation that’s of value here. Questions of listening practice come to mind: Am I in the right place, do others hear what I hear? No two people in the audience perceive the same thing: by splaying it out across the different rooms, the chamber concert’s intimacy is brought into a sharper focus. The way I heard the piece, closing my eyes and sitting on the floor of one chamber, walking backwards from one to the next, was indeed intimate, as was the audience’s strange relationship with the performers, who, instead of finding themselves on the pedestal safety of a stage, were on the floor with us. Some found themselves cut off from the sight of their fellow musicians—only able to communicate with each other through the disembodied sounds of their instruments.

Such was one of the experiments at the Borealis music festival, tucked between fjords and mountains in Norway’s coastal city of Bergen. (The festival provided plane tickets for me to attended.) They described their festival as for eksperimentell musikk, though they might likewise have inverted that description and called themselves an experimental festival for music, given the openness to trial and error.

Deconstruction has been the first step to experimentation for at least a century in many aspects of art and science. Dissecting organisms in the lab and peering through the microscope to better understand the constituent parts of the cell; realizing the social constructs of identity and identity, and working to undo them; the representation of three-dimensional forms by breaking them down on the canvas. Even atonality is in some sense a deconstruction of the tonal. But the value of deconstruction lies in what remains, be it value inherent in the deconstructive process, in something learned, in some new way of hearing, seeing or understanding. In the lab the end-product of dissection shouldn’t be a castrated, chloroformed frog; likewise, de-structured language shouldn’t evict us once again from our Tower of Babel. Musical and artistic deconstruction is no different: most of us have, at some point, sat or dragged ourselves through exhibitions of works that only manage to un-do, and never to re-do, finding that there’s no common language, no footholds or places left with which to grasp and engage. Experimentation and deconstruction can be tricky games to play.

These were some of my thoughts as I made my way around Borealis—not conclusions on the festival itself, rather the product of conversations I had, and of a desire for some kind of barometer by which I could gauge its results. It’s worth making clear here that this was borne out of my relatively un-versed relationship with experimental music. In the first piece of the Future Opera tryptic for instance, which gave three different composers the same components with which to rethink opera, Rebecka Sofia Ahvenniemi produced a trailer for “Beyoncé and Beyond,” where the archetypical “diva” of our time, “born of the dream of a man,” struggles to break out of his dream. In a similar vein to queer, underground pop artist MHYSA’s powerful performance a day later, which under quite different circumstances also forced the audience to confront what it means to view a performance onstage, Ahvenniemi’s “opera trailer” worked outside of the expectations of the paradigm, and by doing so—by presenting a so-called trailer—forced us to doubt whether our “diva” could ever truly escape; whether a performer-protagonist is forever destined for insecurity at the hands (or eyes, or ears) of others. But via a charming and funny second piece, the third part of the tryptic lost me—and it could have been just me. After running the gauntlet of deconstruction the third experimental opera was left incoherent—that it mourned, or its characters mourned, or perhaps just mentioned Laika the Russian space dog was all I could gather, and like poor Laika, I felt very distant and removed from anything within my orbit of comprehension.

But that’s the thing with experimental formats and the imperative to deconstruct one language in order to build another—it might not speak to everybody, or not everybody might know how to use it. Under some conditions they might produce erroneous results, and under others they might be completely coherent, but I got the impression at Borealis that the gaps in comprehension, something I didn’t understand, but that somebody else might, were there to be explored and talked over. While leaving concerts, conversations were less about how well somebody played, or whether so-and-so had seen such-and-such conduct this-and-that and it was better, but rather discussions on what was being challenged, achieved, what worked and what didn’t—subjective experience and subjective results. I thought back to some of the conversations I’ve had and heard while leaving classical concerts in Berlin, and came to the realization that very little of the discourse surrounding what its connoisseurs like to call “art music” treats it like an art form.

Not to say that sound itself is relegated in favor of the theoretical. Knut Vaage’s “Svev,” which translates to something like “levitate,” produced an exact feeling of suspension. The Valen Trio’s instruments sounded like the tightly-wound objects they are—an objectivity corroborated by percussive taps on the instrument’s bodies. A kind of high-tension power line inhabited the music, producing a vertigo I sometimes feel looking out of plane windows at the ground below during take-off, while emphasizing the instruments’ physical properties, their delicate settings and position within the room. But it was when the trio started playing conventionally again, when the impossible texture of sound gave way to the old language of tonality, that the spell was cast—the deconstructed violin, cello, and piano became themselves again in a new light. Through the deconstruction of their constituent elements, their bodies and their strings, Vaage illustrated the grammar of their construction. (I don’t know whether that was his aim or not.) In this respect, the music remained the important element, the language both deconstructed and built up again.

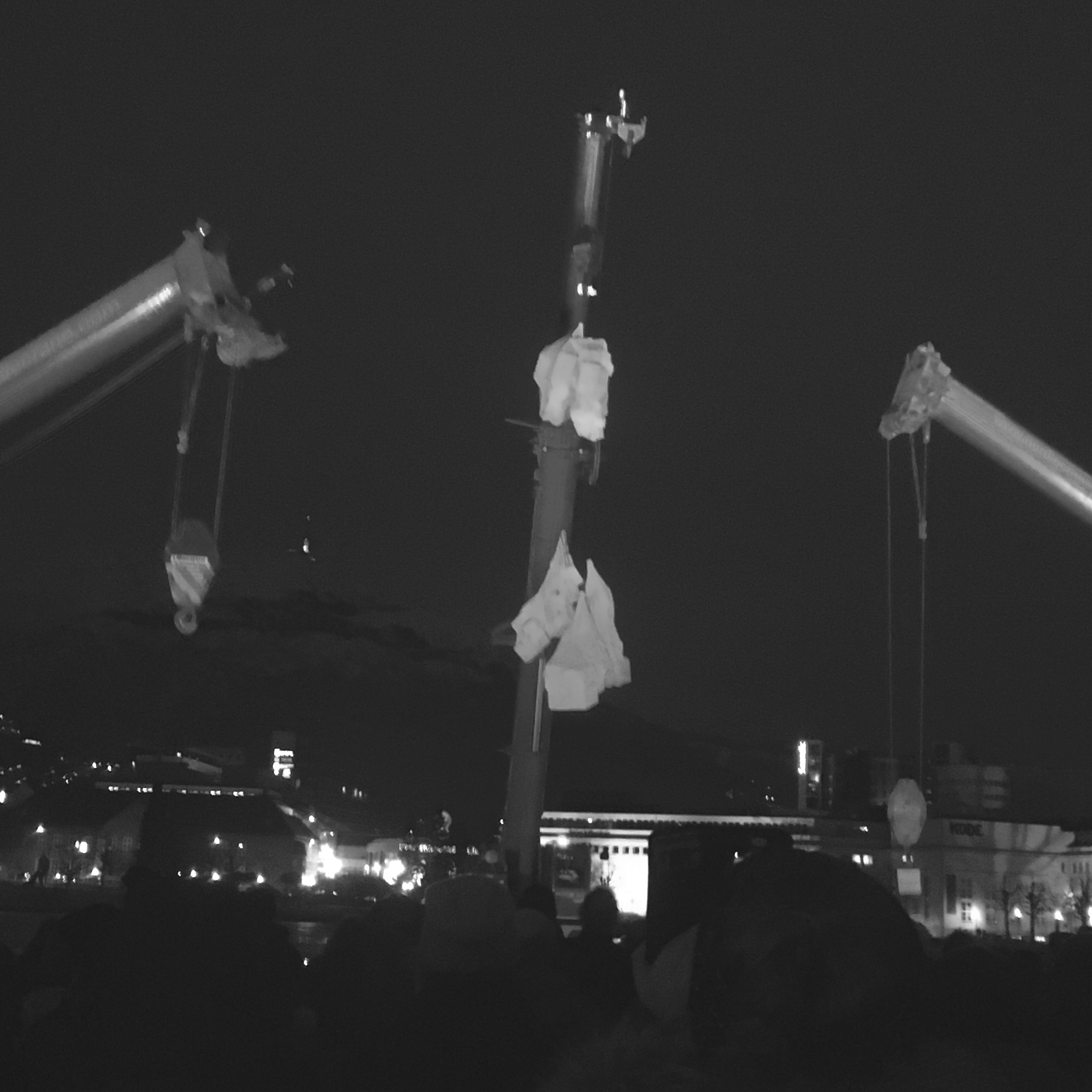

Music was not always the dominant mode of communication though, and some performances were almost devoid of it. There were a hell of a lot of Icelanders at Borealis—so many, in fact, that as one person remarked to me, the island itself might be at risk of unbalance, and could tip and slide into the freezing north Atlantic. One group, the composer collective S.L.Á.T.U.R., created a performance that involved people entrapped in enormous foam geometric shape costumes attempting to make their way through the city and into venues. The shape people—or “geometrists” as they called themselves—did indeed try to play a surprise concert on the closing night, though were somewhat hindered by their outfits. During a panel discussion with the collective, which was interrupted before it began by a monologue about a composer pissing on a piece of fruit he’d dropped into the toilet, one audience member accused S.L.Á.T.U.R. of “dangerously” calling what they were doing music, and likened it to a scientist declaring anything she might please to be “science.” The accusation of danger was a bit much, but their “performance,” (if that’s the right word), did indeed work outside of the grammars of performance and reception to which we are attuned, and it was interesting to see that even at a festival for experimental music, somebody objected to the term being thrown about a little more liberally.

That’s the risk of experimentation. It’s bound to rustle a few feathers in some way here and there. But the openness to do so, and for those feathers to be rustled or not, is what sets valuable experimentation and deconstruction apart from pretentious meddling—at no point did it feel like we had to deem each performance to be brilliant, or the festival itself to be perfect. The thin veneer of the polished and shined finished product, too often given too much importance in the music world (and especially the classical world), was stripped away. The inner workings, those behind the scenes and those participating at various levels were visible; they rubbed shoulders with one another and made conversation in the evenings. No prodigies, no masters, no maestros, no bullshit. I think Borealis deserves special credit here from a publication that tries to write as much as it can about women and non-binary people in music; there was a large proportion of non-male performers or composers. Norway is a rich country, and its culture funding is envied by many of us working across the rest of the world; if there’s a place that facilitates experimentation, then this is it. But concerts were well-attended, people were turned away when they became full—the appetite for new modes of performance, for the deconstruction and rebuilding of new cultural languages, was there regardless. New languages might be confusing, they might fall on deaf ears, or on ears like mine, which don’t always know how to listen, but they are, in any case, tremendously valuable—particularly for building structures up anew. ¶