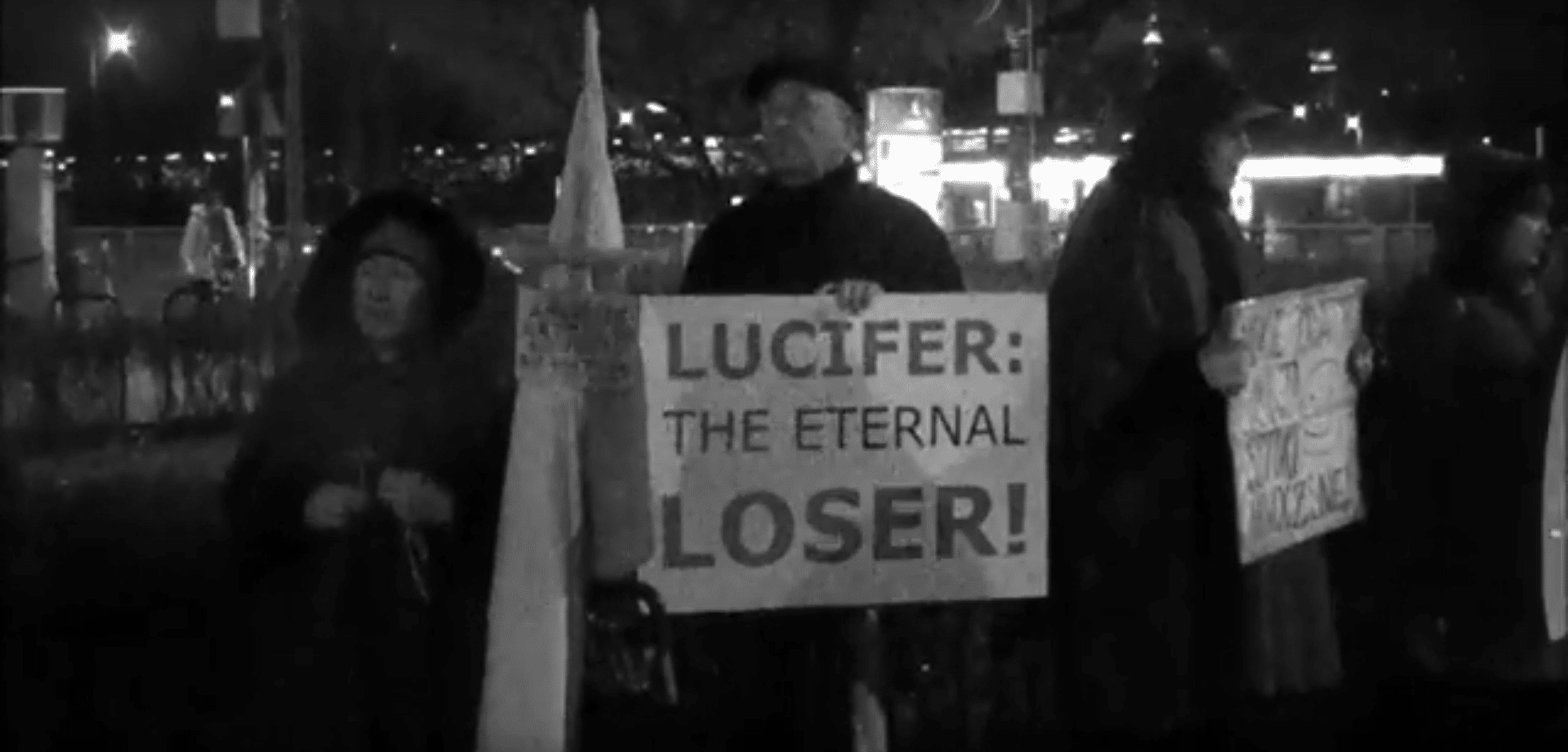

On the evening of November 21, 2015, a scrum of protesters blocked the glass doors of the Teatr Polski in Wrocław, Poland. They were members of the Catholic organization Krucjata Różańcowa za Ojczyznę (Society of the Rosary) and far-right groups such as the All Polish Youth and the National Resurrection of Poland. Piotr Rybak, a notorious nationalist who later served jail time for burning a Jew in effigy, was spotted in the melee. The Catholics prayed for the souls of the director, the actors and the members of the audience. The skinheads hurled insults as they passed. Piotr Rudzki, a former historian and literary director at the Teatr Polski, told us it was “the day when the fight against Polish liberal culture began.”

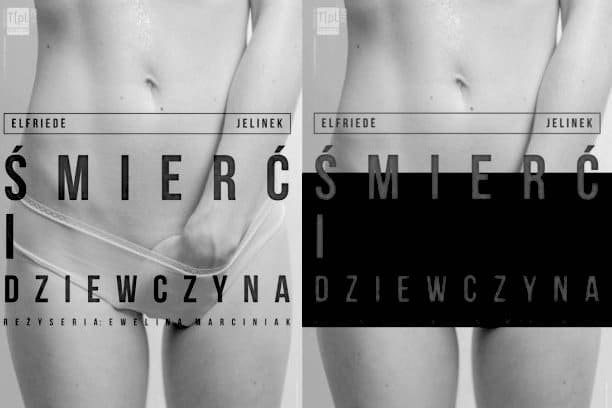

The play was entitled “Death and the Maiden,” based on Elfriede Jelinek’s satirical feminist Prinzessinnendramen and her novel The Pianist. The director, Ewelina Marciniak, had chosen to engage two porn actors from the Czech Republic for the opening of the work. They were to perform sex acts on the darkened stage before the drama proper began. This news leaked before anyone had even seen the finished play. “Three days before the premiere, the situation became so tense that the actors were afraid of coming to rehearsal,” said Marciniak. (The playbook for the protests was similar to those surrounding John Adams’s opera “The Death of Klinghoffer”: an “offensive” tidbit is made public, with no clues to the context or its artistic meaning.) Posters for the play, displaying a slim young woman reaching inside her panties, were vandalized with a thick strip of black spray paint. Several of Marciniak’s invited guests were unable to get past the demonstrators to attend the performance. At the picket line, a protester told the Catholic weekly Gość Niedzielny, “We decide what will be displayed here.”

In a letter dated November 20, the Polish Ministry of Culture and National Heritage called on local officials to suspend the premiere of “Death and the Maiden.” While emphasizing its support for artistic expression, the letter reminded the region that the performance was funded by public money, and noted its concern that young performers were taking part in the play (though they were kept separate from the sex scenes). But Piotr Gliński, the Minister of Culture for the governing right-wing Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (PiS), or Law and Justice party, had been too heavy-handed. The backlash against what looked like an attempt at censorship was swift and passionate, and was reported in the international news media. “It was the first time since the fall of Communism that a Minister of Culture wanted to implement censorship,” Rudzki said. The performances of “Death and the Maiden” went ahead as planned.

It looked like a victory for free speech in Poland. But when then-artistic director of the Teatr Polski, Krzysztof Mieszkowski, was replaced with a little-known actor named Cezary Morawski in 2016, according to multiple people familiar with the theater scene in Poland, the company, once renowned internationally, suffered a major loss in quality. Rudzki, who, after being fired for “disciplinary reasons,” opened a small counter-organization called Teatr Polski in the underground, said that Morawski serves as artistic director, director for individual plays, and actor, possibly in order to collect as many fees as possible. (He also hired his wife as an actor.) He has cut educational offerings, audio descriptions for the blind, and English surtitles. Morawski’s leadership has “catastrophically changed the theater,” Rudzki said.

“Theater hasn’t caught up in becoming a propaganda machine,” said Michał Zadara, a Polish theater director who studied at Swarthmore, before returning to his home country in 2000. “It’s just becoming less important and less relevant.” Although Poland has long been home to an extraordinarily vital theater culture that “plays the role of a forum for the most important political discussions and acts as a sensitive measuring tool for the mood of society,” as Małgorzata Leyko, a professor at the Institute for Contemporary Culture in Łódź has written, PiS appears uninterested in replacing this forum with something more conservative in outlook. They’d rather simply let it die out. PiS “would rather have nothing, that’s really the shocking thing,” Zadara said. Venues like the Polski Teatr “were really exciting and drawing huge audiences, and now all of a sudden they aren’t doing anything.”

The story of the Teatr Polski’s decline is one of rebellion, followed by sweeping, punitive staff firings, pragmatism, then capitulation. That process started in 2015 and is now nearly completed, though certain legal challenges are still pending. (The Polish political system is broadly decentralized, meaning that PiS has not been able to institute all the changes it would like. Still, it has been accused of attempting to pack the courts with loyalists.) A similar process of undermining is now underway at the Stary Teatr in Kraków, a gorgeous, high-ceilinged space, and one of the country’s most historic and prestigious venues.

On November 28 2017, we attended a Stary Teatr staging of “The Wedding,” a classic Polish play from 1901 by Stanisław Wyspiański. It was one of the last stagings by the former artistic director, Jan Klata. Klata, despite not aligning with the PiS government, was widely expected to retain his job, due to his impeccable artistic reputation and careful politicking. (Zadara told us that Klata was even happy to pre-screen and reject productions “that were going to be critical of society and government.”) But when the time came for Klata’s contract to be renewed, a left-field candidate named Marek Mikos was chosen instead. When we attended “The Wedding” in November, no performances were listed for 2018 on the theater’s website, and the actors were boycotting Mikos’s artistic directorship. (A reduced schedule has since resumed.)

Wyspiański’s play, written largely in rhyming verse, seems to prefigure the current political climate in Poland. Sophisticated guests from Kraków attend a peasant wedding in the countryside: they flirt, fight, drink, dance, and search for meaning. In Klata’s staging, a shirtless three-piece heavy metal band on raised platforms accompanied the action. The peasants wore scraps of red-and-white Poland soccer jerseys. The atmosphere at the Stary Teatr was electric. A long line of young people waited in the freezing cold for tickets. “It’s been very full since the directors changed,” a young man at the coat check said. When every seat was filled, people sat on the theater’s steps, stood at the back, and peered through the railings at the action on stage. They scattered at the two intermissions to smoke outside and discuss the play. A central image in “The Wedding” is the scythe, a tool of farming and war, which the peasants clutch tightly—a symbol of their longing for self-determination. During the applause, instead of bowing, the actors stared at the audience and banged the poles of their scythes against the stage: a gesture of support for Klata. The thudding and the clapping seemed to go on forever.

After the audience had finally filtered out, we sat down with four of the actors in the emptied theater. Their “gesture of resistance” finished, the actors seemed listless and the space quietly sombre. They spoke about the amount of time they spent here, rehearsing, performing, and working together—their intimate connection to the stage. The young ones were planning to move to other theaters, in places such as Warsaw, or abroad. The older ones admitted that they would likely stay on. “On the one side you’re pragmatic, and on the other you have your feelings,” a darkly handsome actor named Radosław Krzyżowski said. “Your feelings tell you that you should not work with the new director. But pragmatically, what can you do? I’m 45, I have a family. It’s not an easy decision to say, ‘We’re going to Warsaw.’”

A blond actor named Juliusz Chrząstowski added, “The future looks very depressing. Our theater is one part of the situation with Polish culture in general. I think it’s going to be like the Hungarian scenario. We have signs of censorship; the pressure is for artists to make national culture, not free culture but national culture.” While so far, the changes to theater have affected only the institutions funded by the national Ministry of Culture, Krzyżowski worried that if PiS makes a strong showing in the municipal elections this May, the smaller local theaters, of which there are some 200, could face similar disruptions. He said, “I think the worst thing in this situation is that it’s the beginning.”

Within anything like a normal political climate, the actors’ boycott might have pressured Mikos to resign, but the situation in Poland is far from normal. “It’s great that they’re boycotting,” the ousted director of the Polish Film Institute, Magdalena Sroka, told us in a cafe in Berlin. “But it’s horrible that there’s no effect, only that people respect them for it.” She went on, “Nothing’s changing, the theater is simply not running, so the actors aren’t earning, Mikos still feels great, he’s still receiving donations, and there are no consequences for not putting on the number of plays he should.” This impasse, in which a government-backed artistic director reaps the rewards of heading a cultural institution without producing anything at the level of his predecessors, mirrors that seen a few hours north of Kraków, in Wrocław. Like Zadara, Sroka told us that the government would rather have no cultural production than anything that might not fit its values. She laughed in disbelief while explaining the absurdity of the situation: “The Minister of Culture doesn’t care that the theater isn’t playing…everything is fine.”

Sroka herself bore the brunt of these changes when she was fired from the Polish Film Institute. Her removal was predicated on a letter to the Motion Picture Association of America written by an assistant which she signed, which denounced the situation in Poland: “It is so scary how fast we can turn to absurd censorship, guided by xenophobic nationalists hidden in the shadow of the statue of Christ, the King of Poland…” Sroka maintained that she didn’t write or read the letter before it was sent. “You don’t always read everything, it was a very simple request to get the rights from the academy,” she said. “When I came back from Cannes and read it, I sent an apology to the Minister of Culture, and he sent me a letter back saying that he sympathized with the innocent mistake, and I thought that was the end of the story.” But three weeks later, she was called into vice-Minister Jarosław Sellin’s office, who presented the letter to her again and asked for an explanation.

“They used it as a pretext, but it still took them four months to use it,” she told us. “The letter was sent in May, and it was October when they asked the board of the institute to remove me.” The institute itself sets strict conditions to do so—none of which were met. “The Minister of Culture treated the letter as a crime, as breaking Polish law, but he wasn’t able to tell me which law,” Sroka said.

Sroka’s removal is symptomatic of the wider campaign to alter the institutional makeup of Poland’s cultural scene. Often, the changes being made are nearly imperceptible from the outside. “You can’t see it as a normal member of society, or even as an art-lover,” she said. “It’s something that’s happening day by day, in small increments.” By altering funding policies, swapping artistic directors or terminating contracts, PiS are taking an opportunist approach that doesn’t swap out the engines of Poland’s culture industry, but changes them slowly, piece by piece, cog by cog. And this has a chilling effect. The concertmaster of a major symphony orchestra told us, for example, that now “you watch what you say.”

The day before we spoke to Sroka, the government changed the law to assert its right to hire and fire high-court judges, a move that sees them facing penalties from the European Union, but which they’re sticking to. But rather than iron-fist changes, it’s the government’s sleight of hand in culture that is particularly worrying, since it’s more likely to go unchecked. Cultural institutions have the potential to influence voters in a very real way. Like “The Wedding,” it’s a story of the countryside against urban centers. “People in the countryside work hard, they don’t have time to watch different TV channels, and they mostly just watch public TV,” Sroka explained. “They’re quite smart with propaganda. They’re lying in front of the cameras, but everybody says the same thing in the same words…so you see 10 people saying the same thing and you think they’re [telling the truth].” While the film world might have condemned Sroka’s dismissal as illegal—over 600 filmmakers, including Wim Wenders and Agnieszka Holland, wrote to the head of the Polish Film Institute to express their criticism—the political heavyweights of the EU are less likely to take issue with alterations in the funding and direction of Poland’s cultural institutions, despite their political motives and implications.

On a quaint street in the old town of Gdańsk, a shop sells “Polish Design Patriotic Wear.” A mannequin of a little boy, his hand raised up—it’s his left hand, but still viscerally recalls the Hitler salute—wears a T-shirt reading, “50% Mommy, 50% Daddy, 100% Polish.” The window also features books about the evils of Communism and various red-and-white, medieval knight designs with helmets, swords, and shields. Through an interpreter, the shop owner declined to be interviewed, but his wares were a fitting image of resurgent nationalism in the otherwise pretty and pleasant Baltic city.

Like many Polish theaters, the Teatr Wybrzeże in Gdańsk is a low-slung, unassuming modern building. Adam Orzechowski, a bald man with blue glasses, has been the artistic director there for 11 seasons. His company focuses on less overtly political productions, and has the support of local officials, which means that he has been broadly spared from the upheavals taking place in Wrocław and Kraków. Still, he’s butted heads with PiS officials too. He said that after one play, when actors had staged a protest action, two members of PiS in the audience “walked out and shouted, ‘Shame on you!’” (Shades of Mike Pence at “Hamilton.”) On another occasion, he had a meeting with vice-Minister of Culture Sellin. “He asked whether I could somehow influence the actors not to protest” against the government, Orzechowski said. Orzechowski told Sellin, “I can’t, and I don’t want to.”

The pressure under which he makes art has also grown. He mentioned a play based on the journals of a citizen under Nazi Germany, describing the ways that language changed: he hoped to achieve political “catharsis” in this work by sharply indicting the current government, but felt that he had failed. We wondered if, since Teatr Wybrzeże has not yet been targeted by right-wing protesters, Orzechowski has found himself censoring his own ideas. “It’s a hard question, because it requires the truth from yourself,” he said. “Doing theater is not without pain. But if I lie to myself, I’ll instantly ask myself why—I’ve been doing this for so many years that it’s basically not possible [otherwise]. You have to be honest with yourself.”

Michał Zadara, the Polish-American theater director, summed up his impression of the danger to the arts scene by saying, “Things have changed, but not in the ways that people assumed.” There have been moments of real danger: public funding being suddenly withdrawn from the Dialog Festival in Wrocław because it planned to produce a controversial production by the director Oliver Frljić, featuring the pope getting a blowjob; the PiS government attempting to exert political control over the content of the Museum of the Second World War in Gdańsk; large nationalist demonstrations in Warsaw; the recent ban on the phrase “Polish death camps.” There have also been encouraging signs: the Dialog Festival solicited private donations and was able to continue its performances as planned; passionate opponents of censorship make any hint of it untenable; the checks and balances of the Polish political system are still largely working. “It’s not like all of a sudden we have censorship,” Zadara reassured us. “That can’t happen.”

For now, the quality of the large, renowned, nationally funded public theaters in Poland is what’s at stake. And, as Zadara pointed out, there is a legitimate argument to be made that the government shouldn’t be in the business of funding vomit and feces or porn actors from the Czech Republic. He said, “I don’t agree with it, but it wouldn’t be totally outlandish” not to use public money for extremely provocative art. In any case, this isn’t the real dangerous policy that PiS is pursuing; rather, its focus on the most provocative bits of a given work of art means that its voters will likely consider new art in general something hostile to them, further increasing its neglect and weakening its place as a forum for society in the process.

None of this means that makers of Polish theater have given up on ambitious, provocative work. On March 7, 2018, Zadara premiered a new piece entitled “Justice.” The play consisted of his team’s efforts to research and investigate the 1968 purge of “Zionists” in Poland. No one has ever been held accountable for these actions. Zadara gathered evidence, summarized it, and presented it to a public prosecutor. He hopes to convict the bureaucrats responsible for crimes against humanity. “From its very beginnings, theater has examined the idea of justice,” he has said. And if the survival of such vital, radical art in Poland is in danger, Polish artists don’t seem scared. They are making brave work, and they have audiences behind them. When we asked Ewelina Marciniak, the director of “Death and the Maiden,” whether she was scared for her safety during the protests against her piece, she said no. She had been spending her entire days in the theater working. And anyway, she said, “I wasn’t afraid because at this time I had fallen in love.” ¶