So many facets of classical music culture are holdovers from the 19th century and at odds with 21st century society. To name just a few examples: the sacralization of classical music; the deification of its (male) composers; the snobbery that results when one believes they are listening to a superior form of art; the damaging consequences of a narrow repertoire. Yet in this essay I defend the most Romantic of 19th-century institutions: the concert hall. Yes, the physical manifestations of music worship, structures so Romantic that they wouldn’t be foreign to Richard Wagner. Though some argue that the etiquette for concert halls is outdated, elitist, and partly responsible for classical music’s struggle to find new audiences, concert halls actually provide unique experiences that have become all too rare.

For centuries throughout Western Europe, musicians performed in taverns, coffee houses, homes, town squares, churches—anywhere people might gather. Yet these locations exist primarily for reasons other than listening. Spaces built specifically for music performance certainly existed before the 19th century, but access to them was limited: nobility who had enough resources to employ their own musicians and composers might devote a room of their estate to musical performance. Such a room would most likely not be available to the public, only select guests of the noble host. Often, the performance was less about listening to the music and more about enhancing the host’s image and prestige.

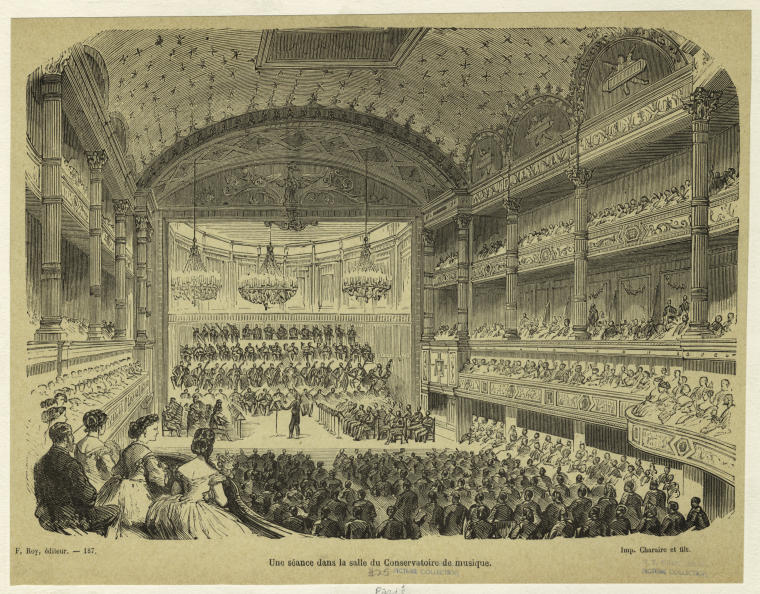

The first opera house open to the public was the Teatro San Cassiano, built in Venice in 1637—just a few decades after composers began experimenting with sung drama within the private estates of Italian nobility. Yet seating in early opera houses reveals that the music was not the chief concern of audiences. Opera and other musical productions were primarily social events. The upper classes attended to see and be seen, so their upstairs boxes tended to face each other across the hall rather than pointing toward the stage. Lower-class individuals standing on the ground floor (where there were no fixed seats) also took in the spectacle of aristocrats hobnobbing in the seats above them. Lights remained on, refreshments were available, and talking was constant throughout the performance. The musical performance was just another event for social drama.

In London, pleasure gardens such as Vauxhall and Ranelagh featured musical performances as one of their many attractions. During a concert, visitors could dine or stroll around the grounds, taking in the beauty of the garden or admiring some statues. People could mingle—or more, in certain discreet areas—while musicians played in the bandstand. Again, music was just one aspect, perhaps even a minor one, in the attendee’s experience.

As has been the case for centuries, there is no shortage of performance spaces today: restaurants, bars, public parks, coffee houses. I’ve attended concerts in bookstores and wine cellars. My youth orchestra rehearsed in the open area of a shopping mall (and yes, the acoustics were terrible). Often these venues are pragmatic—concert halls are expensive, after all, and not all composers or performers can afford acoustically optimal spaces. Many turn this disadvantage into an attraction, trading quality of sound for ambiance, the opportunity to socialize, or the ability to satisfy our taste buds along with our ears. These alternative venues tend to be less formal environments where concert etiquette may not apply. But why did such strict rules of behavior emerge in the first place?

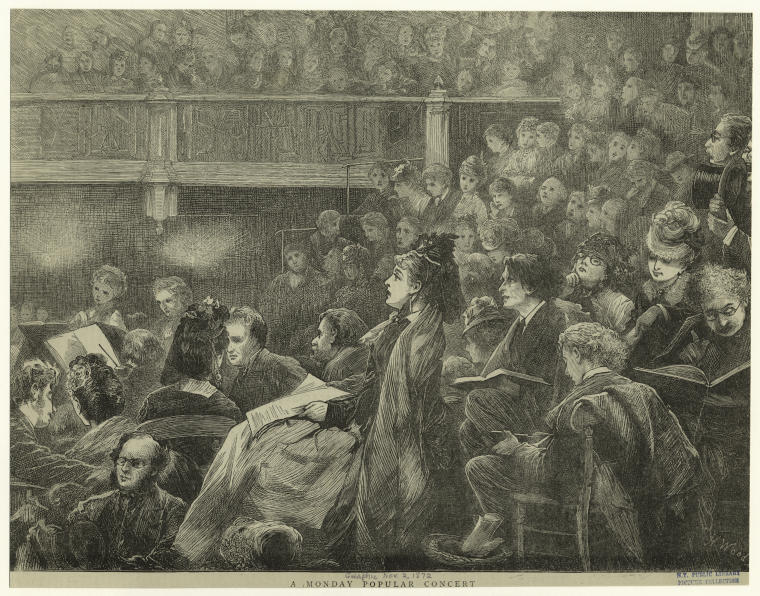

Throughout the Romantic era, several interrelated cultural shifts coincided to make a concert culture that more closely resembles what is expected in concert halls today. Romanticism, particularly in Germany, emphasized the inward experiences of the individual. Music became more closely associated with personal expression, statements from composers to be received by listeners. Also, as William Weber has written, people started making greater distinctions between “high” and “low” art, with the presumption that a person’s taste in music corresponded to their social stature and moral bearing. Furthermore, it became an expectation that people needed to educate themselves about art to fully understand and appreciate it. Music was no longer just the background of social events; it could itself be the focus of attention.

These ideas emerged throughout the first half of the 19th century, contributing to a new, meditative form of listening, notes Meredith C. Ward. This aesthetic experience of music required more from its audience—more education, more concentration, more thought. As music became an inward experience rather than the background of a social function, performance spaces reflected the change: audience seats faced the stage rather than each other. Symphonies came to be perceived as unified works with motives that tied the movements together, rather than separable movements that may not even be performed in succession. Influential conductors like Felix Mendelssohn discouraged applause between movements of works to help audiences sense these connections.

The spiritual treatment of music became manifest in Richard Wagner’s plans for his Festspielhaus in Bayreuth, as he set out to create a space that minimized distractions and fostered attention to the stage. Bayreuth established many policies that remain in force in concert halls today such as extinguishing the lights to leave each listener in a sea of darkness. Interestingly, as James Bennett, II points out, Wagner himself expected clapping and audible reactions to “Parsifal” from the Bayreuth audience, but a miscommunication led to the audience remaining completely silent—a condition they came to prefer.

Our familiarity with this experience—not only in concert halls and opera houses, but in movie theaters—may have dulled our sense of how precious this inward-oriented listening experience would have been before the dawn of recorded sound. If someone wanted to have a private listening experience, their options were mostly limited to playing piano transcriptions and imagining what the orchestra and/or singers would sound like. Today, of course, we can select almost any musical work we desire and have a completely inward, immersive experience by listening on high-quality headphones or stereos in a darkened room…or whatever environment we choose.

If the concert hall no longer provides an experience that was otherwise denied to 19th century audiences, what could it offer us? Our culture is driven by consumerism, where we can manipulate our environment to cater to our individual musical tastes; consequently, music has become ubiquitous to the point where some consider it “aural wallpaper.” Yet the concert hall still provides something unique: the individual aesthetic experience within a communal context. (Not to mention one of the few places left in the Western world where no one is looking at his phone.)

Earlier, I mentioned that movie theaters create an environment similar to that of the concert hall. Yet movies often prompt spontaneous communal responses: gasps at an unforeseen twist, shouts at a scary jump-cut, cheers when a beloved character makes their first appearance or cleverly gains the advantage. Directors of blockbuster movies understand the power of shared experiences and exploit those moments; it’s what keeps many people going to the theater instead of waiting to watch every movie at home.

Classical music has moments like this as well, though they may not be as obvious. When I was an undergraduate taking a course on form and analysis, my music theory professor suggested, “The next time you go to a concert where they’re playing a symphony you know, turn your head at look at the faces of people behind you just as the development section is ending. You’ll see the relief on everyone’s face when the recapitulation comes. Even if they aren’t completely aware of why they relaxed, they could still sense the return of the home key and a theme that they recognize.” As with a movie, a concert is more fun when the venue is full of enthusiastic fans.

This isn’t to say that all aspects of 19th concert hall culture should be replicated. Wagner’s Festspielhaus was very much a church for the worship of music and the visionary composer who created it. Symphony Hall in Boston—the first concert hall to be built according to recent advances in the science of acoustics, in 1900—features an ornate crest bearing the name Beethoven centered at the top of the Proscenium, effectively turning the hall into a shrine for the composer. The sacralization of classical music leads to many problems in the industry, as the quasi-spiritual veneration of musical “geniuses” creates conditions in which the abuse of power flourishes. Yet a change in the way we approach the concert hall would make the environment more accessible without trying to pass classical music as something it isn’t. We can ease up on the strictest aspects of concert etiquette—allow for some expression of our humanity by allowing audible reactions during performances, for instance—to acknowledge the concert as a public experience rather than a faux-private one, even without sacrificing the freedom from distraction that makes the concert hall worth keeping. ¶