Heartbeat Opera’s adaptation of Beethoven’s “Fidelio” achieves what many well-meaning, ostensibly “woke” contemporary music ensemble efforts fail to accomplish. Artistic Director Ethan Heard’s retelling engages directly with the marginalized population it seeks to draw attention to: The “Prisoners’ Chorus” is sung by incarcerated individuals from prison choirs across the United States. Although the opera was composed two centuries ago and sung in German, Heard’s reconceptualization of the opera successfully gives voice to a handful of the 2.3 million individuals currently incarcerated in the U.S. The 2022 version, which has a COVID-friendly digital program, is accompanied by letters from the prisoners recounting the experience of singing in the choir. One of the vocalists writes, “It feels like I’m telling a part of my own story through theirs.”

The U.S., despite comprising roughly four percent of the global population, accounts for 20 percent of the world’s prisoners. It has the highest incarceration rate of any country in the world. Heartbeat Opera’s “Fidelio” gave a fraction of these 2.3 million individuals a chance to be heard; one of the prisoners writes that for a brief period of time, the choir made them feel “accepted as humans, not looked at as numbers.” Heard’s production seamlessly shifts from the micro–the story of a Black Lives Matter activist, Stan, who has been wrongfully imprisoned–to the macro, with its inclusion of the literal voices of six prison choirs. The multimedia reimagining of the “Prisoners’ Chorus” illustrates the widespread effects of mass incarceration in the U.S., or as one prisoner puts it in their letter, “the injustice of the justice system.”

The opera is particularly moving for those of us who have experienced this injustice firsthand. Having lived through the incarceration of a family member, I am familiar with the sensations of helplessness experienced by so many whose relatives and loved ones are incarcerated. Something as simple as talking on the phone—much less seeing someone in person—becomes an ordeal, and these mundane frustrations are compounded by the ever-present knowledge that your loved one is not being treated like a human being. In the opening scene of Heard’s updated opera, Stan’s wife, Leah, grapples with these feelings of helplessness, knowing that Stan is trapped in solitary confinement and there is nothing she can do. When we next see her, she has gone undercover as a guard in hopes of infiltrating the prison and freeing her husband.

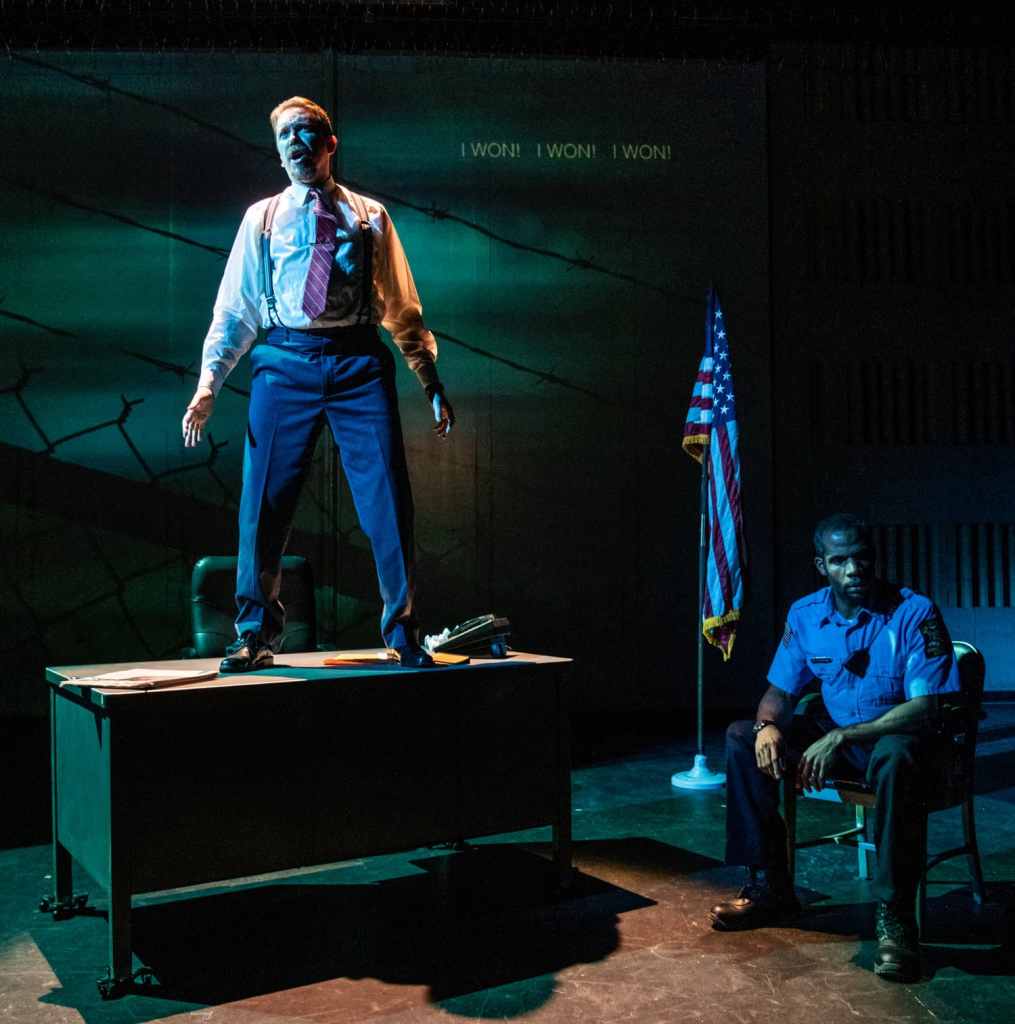

Beethoven’s opera depicts this infiltration and ultimate triumph over injustice. A woman poses as a prison guard named Fidelio in order to free her husband, who has been wrongfully imprisoned by prison governor, Pizarro. In the updated version, Pizarro is a white supremacist warden with a vendetta against activist Stan. Leah, undercover as “Lee,” manipulates prison guard Roc and his daughter Marcy in her efforts, ultimately leading them both to question their positions as people of color aiding the racist project of mass incarceration. In Lee’s final confrontation with Pizarro, instead of drawing a pistol she whips out a cell phone that she uses to document evidence of the warden’s cruelty. As one of the prisoners puts it in their letter, “The story of ‘Fidelio’ is a heroine’s tale… A powerful woman who would not let wrongdoing go by.”

The updated production trims the original story down to 90 minutes. The music, arranged and directed by Daniel Schlosberg, is pared down to two pianos, two cellos, two French horns, and percussion. The recitative is spoken in new English dialogue by Heard and Marcus Scott, and incorporates references not only to the Black Lives Matter movement but also to the January 6 insurrection at the U.S. capitol. In a recent interview Heard said, “I like that the audience experiences these intimate, contemporary American dialogues and then hears these grand German arias.” In their letters, the incarcerated singers wrote of the challenging, yet ultimately rewarding, experience of learning the German words so quickly. As one prisoner put it, “what surprised me was how… you can still find passion within you even in other languages.”

The incarcerated people whose words we read in these letters, and whose voices we hear in the “Prisoners’ Chorus,” are members of choirs from Iowa, Ohio, Kansas, and Minnesota: the Oakdale Community Choir, KUJI Men’s Chorus, UBUNTU Men’s Chorus, HOPE Thru Harmony Women’s Choir, East Hill Singers, and Voices of Hope. I should mention that the opera’s 2022 tour also features the voices of a handful of incredible non-incarcerated vocalists: Kelly Griffin, as Leah, and Corey McKern, as Pizarro, stood out. Daniel Schlosberg’s musical direction and conducting contributed an unassuming vigor that underscored the liveliness and momentum of the narrative. But the prison choirs are truly the stars of the show.

Heartbeat Opera deserves praise for their direct engagement with the communities their production concerns itself with. I’ve written elsewhere about the problems that frequently arise when classical music groups attempt to engage in a dialogue with “the news.” Despite good intentions, many (if not most) organizations fail to effect any tangible change with their politically-oriented programming. The efforts to “draw awareness to” a political issue instead devolve into virtue signaling that is empty of genuine involvement with a given cause. And ensembles that focus solely on enhancing representation for “marginalized populations” mostly serve to “force [under-represented groups] to compete for the privilege of being tokenized.”

By contrast, Heartbeat Opera subtly “draws attention to” the crisis of mass incarceration by letting those who have firsthand experience speak for themselves. Their endeavor brought about tangible (if temporary) change to the lives of those most impacted by the prison industrial complex.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

Many prisoners express feelings of gratitude and hope that have arisen through the “Fidelio” project. Kerron Brantley writes that “the experience has been a blessing” and that “any depiction that humanizes inmates is a beautiful thing for the community.” Providing such opportunities for subjugated groups should become the bare minimum for civic-minded classical music programming. Although the program does not offer concrete suggestions for those who wish to become more involved in prison reform, hopefully audience members will be jolted from complacency by Heartbeat Opera’s adaptation. I’m not sure how anyone could fail to be moved by the letter from Mark B. Springer: “Having been incarcerated for 29 plus years, the context of Fidelio I identified with… I’d love a chance to live free. I was 20 when I committed my crime… I’ve spent 60 percent of my life in prison. Think of me; remember me in your prayers.” ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.