A specter is haunting Europe—the specter of killer whales. Since 2020, pods of orcas have been attacking ships and yachts in European waters. As of about a month ago, more than 500 yachts had been attacked off the Iberian Peninsula alone. This summer, other aquatically-inclined mammals have joined their orca comrades (orca-mrades?), with reports from California of both sea lions and otters attacking surfers. Which: Good for her.

There are plenty of works in classical music about the ocean that show the sea as dazzlingly beautiful, calm, and serene. This list does not include any of them. Instead, we’re taking a look at sea-inspired works in which the ocean fights back, takes no prisoners, and fucks humans up. While many experts in orca studies argue that these last few years of attacks are not a Melville-inspired revenge-plot against man, humanity has never let science get in the way of a good story.

Richard Wagner: “Der fliegende Holländer” (1843)

The existential threat of open waters is never far from Wagner’s music. “How happy I should be to die in a storm at sea,” he wrote to his father-in-law in 1853. In this way, “Holländer”—while far from the gesamtkunstwerk-y transcendence of “Parsifal,” “Tristan und Isolde,” or the “Ring” Cycle—is one of the works closest to the composer himself, because it renders most literal both his desire “for peace from life’s storms,” and for the storms.

The Dutchman’s is a cautionary tale about man’s hubris in the face of nature: He earns his curse by swearing to clear through some choppy waters if it takes him until Judgment Day to do so. Hearing this vow, the devil takes him up on the offer. Wagner was probably too far adrift to reach the level of self-awareness necessary to realize that he, too, was a victim of his own chutzpah, and that the storms were often of his own making.

Iannis Xenakis: “Kyania” (1990)

In its isolated form, water is clear, translucent. But the sea is murky, mired in its own ecosystem (to say nothing of the man-made objects that have invaded, with the force of Genghis Khan’s Mongol Horde, that same ecosystem). The sea is a recurring motif in the works of Iannis Xenakis, who grew up surrounded by the Mediterranean. It was a source of pleasure (he spent most of his summers along the sea even as an adult). Having fought with the communist-dominated Resistance during World War II, Xenakis was later targeted as part of an anti-communist purge and sentenced to death for political terrorism. The Mediterranean was his risky path out of Greece; he was smuggled onto a cargo ship heading to Italy. He was 24 at the time of his escape, and these early events of his formative years left an indelible mark, physically and psychically.

Densely woven and textured, his “Kyania” is written for 90 musicians and takes inspiration from Xenakis’s beloved Mediterranean (the name a distant cousin of “cyan”). Within thick clusters, we can intuit the full range of meaning this body of water had for the composer: a natural balm and source of azure-hued beauty, but also the same wine-dark sea that claimed Odysseus’s troops and Allied naval forces. It’s both salvation and obliteration, a spiritual and natural ecosystem that moves in strides too powerful for any one human to match.

John Adams: “Ocean Chorus” from “The Death of Klinghoffer” (1991)

John Adams likens the choruses in “Klinghoffer” to those found in a Bach Passion; they serve as a scaffold for the story, pausing the action of the chaotic hijacking plot to locate its emotional pulse. The opera begins with choruses of exiled Palestinians and Jews, but the chorus in “Klinghoffer” also takes on the role of physical and metaphysical landscapes.

The “Ocean Chorus” serves as an interlude between the first and second scenes of the opera. The ship has been seized and its crew and passengers held at gunpoint. Scene One ends with the mundane: The unnamed Captain of the Achille Lauro asks a crew member for coffee and sandwiches to share with hijackers Molqi and Mamoud. They can choose the food, and he will eat first—a sign of trust. An unsettling calm takes over the score, murky like the depths of the ocean, a “landscape of night,” per Alice Goodman’s libretto, “untouched by storms, deep-silted with the motes of carrion which stand for light.” Adams renders this synesthetic bit of text with grainy sediment and the aura of death. When the chorus concludes that “God rests in nothing,” the music doesn’t suggest that God never rests. Rather, it gives voice to the pervasive and prophetic nothingness in which He resides.

Benjamin Britten: “Four Sea Interludes” from “Peter Grimes” (1945)

The wordless interludes of “Peter Grimes” function much like the choruses in “Klinghoffer,” carrying listeners from one scene to the next. The poetry of Goodman’s libretto, however, is carried entirely through Britten’s music, giving shape to both the harsh British coastal town and the equally rough emotional terrain of its residents. The inevitable conclusion is the misanthropic, misconstrued Grimes being driven to suicide at sea.

What we really need is a staging of “Grimes” that rebalances justice with the main character’s shitty neighbors: Yes, he takes the suggestion of the old sea captain and goes out to the water, but instead of dying, he’s taken in by a pod of whales who immediately accept him as one of their own. Reprising the chorus “Him who despises us we’ll destroy,” they set upon the town (beginning with Mrs. Sedley and Bob Boles). Nature heals. It’s beautiful.

Kaija Saariaho: “Amers” (1992)

Written while she was at IRCAM, Kaija Saariaho’s “Amers” takes its name from the wayfinding beacons used along the French coastline. It’s also a sonic companion to the French word for the sea, “la mer” (to be out to sea is à la mer). This sequence of parallel and perpendicular meanings comes through in the cello part of “Amers” which, while not a concerto, has moments of its soloist playing both with and against the orchestra. It is both the sailor and the beacon, navigating dark waters that are as beguiling as they are foreboding, like the proverbial razor blade coated in honey.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

Peter Maxwell Davies: “Sea Elegy” (1998)

In 1974, a 40-year-old Peter Maxwell Davies moved to Orkney, an isolated archipelago off the northeastern coast of Scotland. The more he became steeped in the landscape of his new home, the more the ocean became a recurring theme in his works. This shift coincided with a growing ecological movement in the UK that Davies also worked with, at times explicitly. His “Farewell to Stromness” was written as a protest song against uranium mining on Orkney. The 1993 Braer oil spill that devastated the coast of Shetland with over 90,000 tons of crude oil horrified him.

As fiery as Davies’s work can be—particularly the psychological storms of pieces like “The Lighthouse” and “Eight Songs for a Mad King”—his “Sea Elegy,” set to four poems by George Mackay Brown, is a quiet riot. Britten-esque solo vocal lines rise up from chorus and orchestra before sinking again, almost like a stretched-out version of the brief and hushed introduction to Verdi’s Requiem. We anticipate the fire of a “Kyrie” and “Dies irae” that never come; instead, we’re left to flounder in this 15 minutes of low-grade fever. Truly unsettling.

Ellen Reid: “Floodplain” (2022)

Begun in 2020 and radically reconfigured before it was completed two years later, “Floodplain” is lush and gorgeous, a Southern Californian version of Rimsky-Korsakov’s “The Sea and Sinbad’s Ship.” Until it isn’t. Reid was inspired by the fluctuating role of a floodplain in nature, a fertile ecosystem that can also turn dangerous depending on the weather. In an increasingly unpredictable meteorological era, this can be a volatile contingency. For Reid, the pandemic helped to reinforce this duality: “my concepts of unpredictability and the creative fertility found in it were fundamentally re-shaped,” she explains in her program note. Motifs pass through a Möbius strip, beginning as idyllic before turning hellish. The end reminds me of “Götterdämmerung,” when the “Rheingold” theme reemerges after so much havoc wreaked in its wake—another loop of the Möbius closed.

Ethel Smyth: “The Wreckers” (1906)

Going on vacation with Ethel Smyth, as Leah Broad once noted, was not for the faint of heart. Her love of the Cornish seaside could be punishing: On one trip, her sister, Violet, fell behind; Ethel’s solution was to tie her dog’s collar around Violet’s waist and have Violet’s husband drag her along. Ethel’s idea of a good time was going to a cave like Piper’s Hole, which—with giddy Christmas-morning energy—she likened to the underworld, complete with Charon’s boat.

Such toughness and despair worked its way into “The Wreckers,” which adopts the same Cornish setting as its own, and took as inspiration the stories Smyth heard of the old practice of “plundering of ships lured onto the rocks by the falsification or extinction of the coast lights; the relentless murder of their crews; and with it all the ingrained religiosity of the Celtic population of that barren promontory.” A forbidden romance set against this backdrop ends with the lovers dashed on the rocks of Piper’s Hole.

Anna Clyne: “Night Ferry” (2012)

The gritty peril of Smyth’s “Wreckers” resurfaces in Anna Clyne’s “Night Ferry,” which begins in a vortex of swirls and eddies and serves as a guide through what Clyne calls “the ungovernable and dangerous.” On the recommendation of Riccardo Muti, Clyne also looked to Schubert’s Ninth Symphony for inspiration, as “Night Ferry” was originally commissioned to pair with that work.

The name of the piece comes from Seamus Heaney’s “Elegy for Robert Lowell,” in which he describes his fellow poet as that type of vessel, “thudding in a big sea, the whole craft ringing with an armourer’s music, the course set wilfully across the ungovernable and dangerous.” Both Schubert and Lowell suffered from forms of manic depression (categorically diagnosed in Lowell’s case, posthumously in Schubert’s), the mood swings of which Clyne likens to the effect of being pitched on harsh waters. Moments of clarity abound, but eventually the coast lights are extinguished.

Thomas Adès / Henry Purcell: “Full Fathom Five” (2012)

In Adès’s “The Tempest,” Ariel’s “Five Fathoms Deep” is a vertiginous and brittle sopranic atrophy, both of Ferdinand’s perception of his family unit (his father is the one whose bones have turned to coral at the bottom of the sea), and of Ariel’s servitude to Prospero.

Conversely, Henry Purcell’s version of the soliloquy, as arranged by Adès, is a pastoral idyll. The meaning of the text is the same, but its musical lines are more quietly triumphant. Reportedly, the orcas are big fans of this version.

Missy Mazzoli: “Violent, Violent Sea” (2011)

“LOUD BUT SLOW. LIGHT BUT DARK. VIBRAPHONE. HOW TO DO THIS?” read Missy Mazzoli’s initial notes for the work that would eventually become “Violent, Violent Sea.” The surface of this piece gleams with flickers of woodwinds and plucks of violins, but underneath it are tectonic plates of brass and low strings moving with stillness: a subdued terror underneath a layer of high-pitched beauty. Uniting the two, connecting the rippling surface water to its colder depths, is—naturally—the vibraphone.

Philip Glass: “A Descent into the Maelström” (1986)

In the midst of this summer’s Titan submersible saga, I was reminded of a line from Edgar Allan Poe’s “A Descent into the Maelström”:

After a little while I became possessed with the keenest curiosity about the whirl itself. I positively felt a wish to explore its depths, even at the sacrifice I was going to make; and my principal grief was that I should never be able to tell my old companions on shore about the mysteries I should see.

In 1986, Philip Glass was commissioned to write a new work for the Australian Dance Theatre, and opted to adapt the same Poe story. His aim was “not so much to interpret the story but rather to extrapolate from it a new work that would articulate in theatre form the sense of the original.” Poe’s text becomes subtext, his words hang in the ether of Glass’s score, although the story of a Dutchman-like figure vaingloriously chasing down a storm at sea could, he points out, be read in sync with the score.

Writing of “Koyaanisqatsi” and Glass’s earlier theatrical work, “The Photographer,” Susan McClary notes that Glass’s build-ups, which then pull the rug out from under the listener’s feet at the last minute, teach us “how very programmed we are to desire violent annihilation through the tonal cadence, and our frustration at not attaining the promised catharsis reveals to us the extent to which we are addicts in need of that fix.” I’ve thought about that image a lot in the wake of OceanGate, too.

Ewan Campbell / Felix Mendelssohn: “Hebrides Redacted” (2022)

In writing “Maelström,” Philip Glass viewed the musical format as something akin to 19th-century Romantic operas and tone poems. Mendelssohn’s “Hebrides” Overture, written after a trip to Scotland in which he most likely encountered some of the region’s humpback whales, fits soundly into the latter category (while also paving the way for composers like Smyth and Davies). It would be easy enough to include that work on this list and call it a day. But last year, composer Ewan Campbell teamed up with environmental economist Matthew Agarwala for the “Hebrides” with a twist. “When Mendelssohn wrote the ‘Hebrides’ Overture, there were about 30,000 humpback whales in the sea,” Campbell explains, adding that Mendelssohn’s score has about the same number of notes. Dividing the score into decades, Campbell then began removing (or redacting) notes in proportion to the decline of the whale population over time. A physical manifestation of what Agarwala calls “nature going quiet.”

Laurie Anderson: “John Lilly” (1995)

“John Lilly, the guy who says he can talk to dolphins, said he was in an aquarium, and he was talking to a big whale who was swimming around and around in his tank. And the whale kept asking him questions telepathically. And one of the questions the whale kept asking was: ‘Do all oceans have walls?’”

You’ve come a long way, baby beluga.

Bonus: Alan Hovhaness: “And God Created Great Whales” (1970)

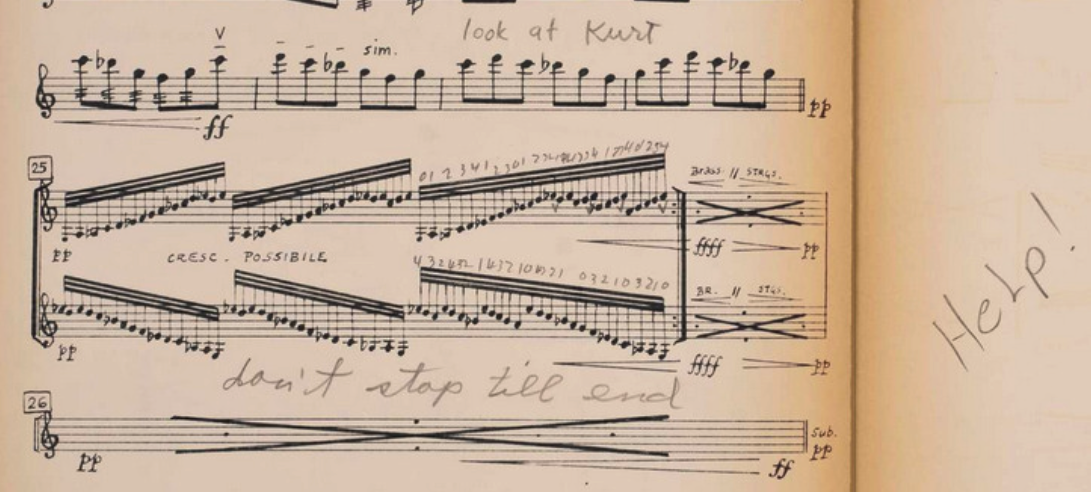

Hovhaness’s tone poem, complete with pre-recorded whale sounds, was commissioned by the New York Philharmonic and in hindsight served two purposes: It was a key cultural moment in the burgeoning Save the Whales movement. It also led to some of the saltiest score marginalia you’ll find in the Philharmonic’s Digital Archives.

The ocean in Hovhaness’s world may not have posed a threat, but the first violins seem to have felt that way. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.