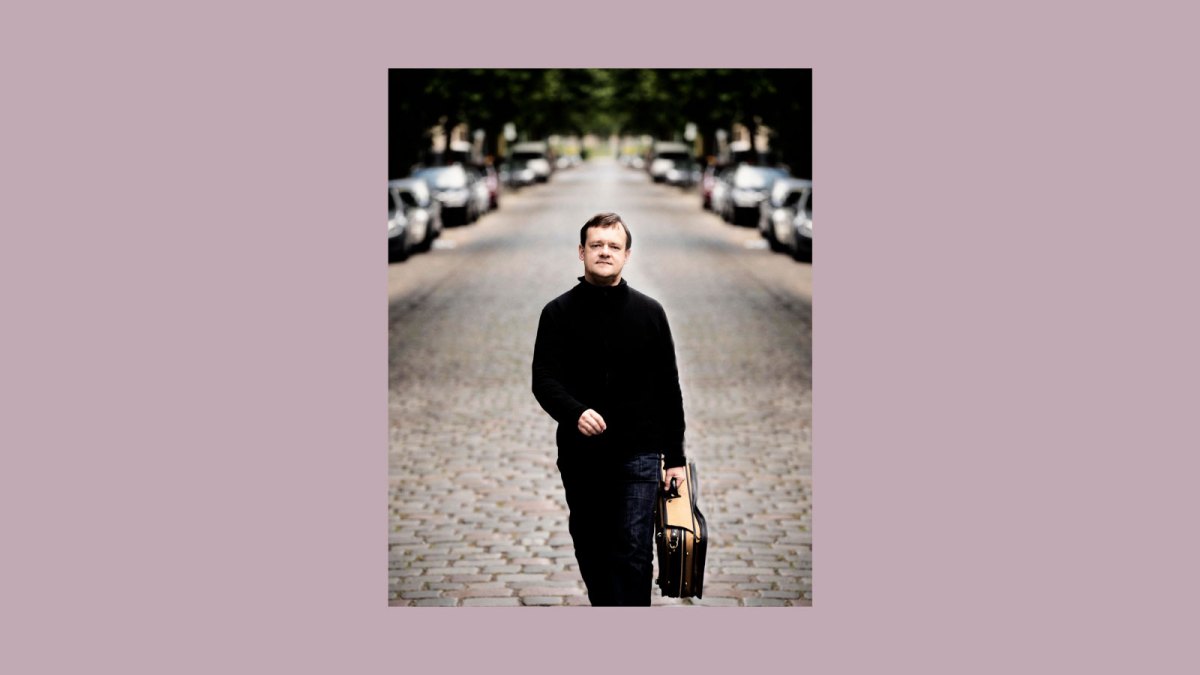

For over 30 years, Frank Peter Zimmermann has been one of the best and most successful German violinists on the international concert circus. Now seemed like a good time to take stock and look both backward and forward. I reached the 57-year-old on FaceTime from his house in Cologne. He apologized for canceling an interview at the last minute in the spring. “The week wasn’t so great artistically, so I was annoyed and not in such a good mood,” he said.

VAN: What happened?

Frank Peter Zimmermann: I’d been looking forward to a concert, but then it didn’t fit as well as I’d hoped with the conductor and the orchestra. There were a lot of little details we would have needed to rehearse, but the conductor would have had to go along with it and add his own input. That just wasn’t happening.

Does that get under your skin?

Yes, after almost 40 years as a soloist, I have certain standards. The Brahms or the Tchaikovsky concertos flow on their own, but not, say, Schumann or Alban Berg. They require everyone to do their part, and if that doesn’t happen, the effect isn’t there—no matter how good the soloist may be. That’s frustrating.

Do you get involved in the rehearsal process more than you used to?

Yes, very much, for some people it’s probably almost too much. [Laughs.] There are some pieces I’ve played over a hundred times; I’ve played the Beethoven concerto over three hundred times. At that point you have certain ideas, and you want to shape everything with the other musicians, like you’re playing chamber music.

Are there orchestras or conductors who say, “We’re not going to invite Zimmermann anymore, he interferes too much in rehearsal”?

It hasn’t happened to me with orchestras, but with conductors you do notice when they stop wanting to work with you. When I was young, I played with the great old maestros—Wolfgang Sawallisch, Christoph von Dohnányi, Lorin Maazel—when and how they wanted. I was a little like a deer in the headlights. I remember some performances of the Mozart concertos, when I was in my early 20s: I wasn’t even allowed to play the whole piece with the orchestra. The attitude was, First we’ll rehearse the Bruckner symphony, then we’ll do a bit of Mozart at the end. There’d be 15 minutes of rehearsal time for a 22-minute piece. It was just kind of tossed off.

So that doesn’t happen anymore?

Not really, now people have a certain respect for me. Conductors often contact me in advance to ask about my ideas for the piece. It’s gotten a lot better. But orchestras still start rehearsing the symphony two or three days before the first concert; they don’t usually get to the violin concerto—no matter how hard it is—until the evening before the concert. Often that means overlooking a lot of details, there’s a kind of uniformity to the interpretation. A virtuoso pianist can stand up to the orchestra; as a violinist you often have no chance if it’s too loud or not subtle enough.

There’s a story about a failed collaboration between you and conductor Sergiu Celibidache. What happened?

Celibidache wanted to teach me the Brahms concerto. This was in the fall of 1982, I was 17. We were planning to do a massive tour with his Munich Philharmonic. He had asked me to come to see him a year in advance. One of the first things he said was that I was just playing the skeleton of the music and that now we’d have to form the flesh. Then he worked on the first movement with me for four hours. He told me exactly how to play every single note; I didn’t even know who was holding the violin anymore. He also told me to do a lot of things that went completely against my personality. I would never have played it so slowly, so ceremoniously. In a few spots he said that Brahms composed it wrong… it was pretty bizarre at times.

Did you tell him then and there that you didn’t want to play the tour?

No, I couldn’t say it to his face. I flew home, then I wrote him a letter.

Did he answer?

No, but ten days later, an invitation from Lorin Maazel arrived, to play with him and the Vienna Philharmonic in Salzburg. That’s how my international career began. And strangely, in the Brahms concerto there are still three or four spots where I always think of Celi, where I play it as he wanted.

You once said that you come from “a simple background” and that you felt out of place in the very often upper-middle-class, even elitist world of classical music. Can you give an example for one of those moments?

I’m from the provinces, and I was very shy about approaching people. I had a lot of support early on. By age 13 I wasn’t required to attend school; I studied violin in Berlin and Amsterdam. Still, I was alone most of the time and grew up very isolated. When my international career started, at 19, my dad often came with me. I remember my Paris debut, my private French teacher came with me. I’m still shy to this day. I don’t like to communicate with the audience very intimately or use visual things to focus its attention on me.

You’re from the industrial Ruhrpott in northwestern Germany. Does that mean you feel more at home playing with, say, the Duisburg Philharmonic than at the Salzburg Festival?

That’s for sure. [Laughs.] I’m just not a star. I understand that the Salzburg Festival would rather invite people like Lang Lang or Anne-Sophie Mutter than someone whom no one’s ever heard of, or whom only connoisseurs know. I’m not for the Coke-drinking masses who sit inside the Grosses Festspielhaus. But to be honest, I’m not interested in those kinds of gala events anyway.

Has your “shyness” ever bothered you?

Not really. I’ve always thought that if people want to hear my concerts, then they’ll make the effort. I’m sure I could have done things that would have increased my profile in the media. I mean, I rarely give interviews. But to go on daytime TV and play with a wind band or whatever…that’s not me. I’m not capable of it, even if it ends up selling more CDs.

Are you relieved that you’re not a young artist coming up today, when communication with audiences in person or on social media is so essential?

I still think that even for really young artists, if you have the right people behind you—a few conductors or important promoters who keep inviting you and with whom you can develop over the decades—then you can have a major career without the fuss.

You play with palpable ease and confidence. As a listener, I don’t hear the difficulty of what you’re doing. Where does that come from?

That’s how I was raised. I started off playing the easiest chamber music with my parents, who were both musicians. My first important teacher, Valery Gradov, made sure that I was relaxed when I played. I was about ten when I went to him. Before that I was with another teacher who was very good, but I kept getting stiffer. Gradov helped me to be relaxed again, and it stayed that way.

Is it hard to keep that up?

Yes, you definitely don’t get more relaxed as you age, with all the ideas you have. I think I’m still very relaxed, but there’s an incredible amount of practice behind it. Like many Russian teachers, Gradov made sure that you practiced the technical exercises every single day, so that you were relaxed even in the most technically difficult passages. Before every lesson, I had to play Kogan études, scales and double stops. People who say they can play at the drop of a hat, or only practice for two hours a day… I’ll never believe that Heifetz or Horowitz only practiced two hours a day.

Do you get stage fright?

It keeps getting worse the older you get. It used to be less of a problem, I was almost brash.

Why?

Your standards get higher. The best time for a violinist is probably around 45. That means that you need to work hard just to stay at the same level, and even harder if you want to improve.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

Many violinists stop playing at 60. The posture for violin playing isn’t exactly natural. Is that something you’ve thought about?

Yes, two years ago I had a slipped disc. As a violinist your spine is basically bent your entire life. I try to make up for it by getting on the treadmill every morning and doing a few exercises. Nathan Milstein played until he was 80, but most violinists start getting worse in their mid-60s. I’m aware of that; I know it might affect me too.

Does the thought scare you?

We’ll see. There’s a lot of chamber music where you’re not in the spotlight so much. I’ve been wanting to play piano trios again for a long time—unfortunately I stopped 15 years ago, when Heinrich Schiff died. It’s an unbelievable repertoire. Of course, the time comes when you don’t play Bartók’s Second or Tchaikovsky anymore. But there are still composers whose music you play your whole life, and others whose music you love above all for a certain time, but which you move away from again.

For example?

I used to love playing the Russian repertoire: Prokofiev, Shostakovich, Tchaikovsky. Meanwhile that’s been replaced by Bartók, whom I place on the same level as Beethoven and Bach—especially his violin music. I recently recorded his concertos, solo sonatas, and rhapsodies, and right now I’m working on the violin sonatas with Martin Helmchen. That’ll be a milestone for me.

I’ve played the Britten concerto often and love it very much, but I’ll probably stop playing it at some point. Same with the Glazunov concerto. Milstein kept playing it even as he got really old, but I don’t see the point. There are young people who can play these extremely difficult passages, where you need to be like a robot, with the left hand—why should I put myself through that when I’m 60?

Trumpet player Håkan Hardenberger once told me that his wife swore to him that she’d tell him when his performances were getting embarrassing.

My wife is strict in the same way, she’d definitely tell me. That’s the worst, when the downfall comes. Some artists keep improving as they get older, like a good vintage, and others keep getting worse for 20, 30 years. And then some die suddenly. I’m not sure what I’d prefer. Maybe like Kurt Cobain: “It’s better to burn out than to fade away.”

Off the top of your head, do you know how many recordings you’ve made?

Around 60, I guess.

You started recording early. You’ve done three or four recordings of all the Mozart Concertos, for example. If you compare your early interpretations of the Mendelssohn concerto (1982) or the Beethoven concerto with Christian Thielemann (1986), for example…

Oh God, you’ve really been rummaging around.

…with the later ones, it’s striking how different they are. Can you describe the history of your changing interpretations?

Like every young person, I had a role model who influenced me and whom I tried to emulate. For me it was David Oistrach. My early interpretations were very romantic, almost a little old-fashioned. Oistrach could get away with it; I’m not sure I could. At some point I got sleeker, more classical. That first recording of Beethoven with Christian Thielemann that you mentioned is extremely slow, maybe one of the slowest first movements that’s ever been done. In my most recent recording, from 2019, with the Berlin Philharmonic and Daniel Harding, I think we were five minutes shorter in the first movement alone—with the same cadenza.

Listening to you talk about your old recordings, it’s almost as if they embarrass you.

Oistrach is still my great role model, his way of playing is inimitable. But I wouldn’t go in the same direction anymore.

Are violinists still allowed to play like that?

They are definitely allowed to, I just wouldn’t listen to it. To be honest, I’ve always been a huge fan of Grigory Sokolov, I still am. There’s probably no more important pianist alive than him. But I can’t stand his Beethoven sonatas. All the edges have been smoothed out, it’s so romanticized, stylistically it has nothing to do with Beethoven. I recently had to walk out of a concert, because I couldn’t listen to it

You probably don’t listen to your old recordings then?

My recordings? God no, that would be a cruel punishment. Who knows, maybe I’ll play more romantically in 20 years. It goes in phases. Although: When it comes to the First Viennese School repertoire, I’ve been going in a certain direction for a while now, and I don’t think I’ll go back to the way I played that music at the beginning of my career. Even playing Brahms and other romantic composers—I’ve realized how many interpretations follow stylistic ideas that come from the 1940s and ‘50s. The wide Hollywood sound didn’t exist before then. It’s impossible to play Brahms better, within that style, than [Henryk] Szeryng or [Pinchas] Zukerman: without coming up for air, with such an intense tone. But is that right? Doesn’t the music have something declamatory as well?

You’ve never recorded the Bach Sonatas and Partitas for solo violin. Why not?

I didn’t have the confidence. Three or four years ago I wouldn’t have thought that I’d ever do it. I haven’t played the sonatas and partitas for years, not since 1998 or something, and even then just three or four, not all six. In every cycle there are always two or three pieces that you don’t like as much. For me it was the first Partita in B Minor, with the four doubles. But the main problem was that I’ve been on the professional hamster wheel for the last 30, 35 years, and never had time to relax and take the time to focus on the pieces. Then the lockdowns happened in March 2020 and all of a sudden I didn’t have anything in my calendar until the following summer. Even when I started recording the first two partitas, in July 2020, I told [Zimmermann’s Swedish label] BIS, “Please don’t be mad, but if I’m not happy with it, you’ll have to deal with the financial loss if we decide to kill the project.”

Is there repertoire that you’d still like to record?

I would like to take another stab at the Elgar concerto in my old age. It’s been more than 20 years since I last played it, it would be a different challenge. Then there are a few sonatas that are definitely missing: Brahms, Bartók, Schumann, Fauré. Maybe one day I’ll do the Beethoven piano trios again, that would make me really happy. Besides that, in terms of violin concertos, I think that’s pretty much it. The virtuosic ones never really interested me, and probably won’t do so in the future. Maybe another world premiere some time. But really, the Bach pretty much completes it.

What about places you’d still like to visit?

At this point I don’t like to travel far, especially when there’s a different time zone involved. We have such wonderful places to play in Europe, including Eastern Europe. Seven or eight years ago I played the Dvořák concerto in Los Angeles in Disney Hall, three times. An excellent orchestra of course, a good conductor. But Los Angeles is nine hours behind: If you’re going to take it seriously, you should really get there eight days in advance, otherwise you’re playing completely jetlagged. A week later I was in the Rudolfinum in Prague with the Czech Philharmonic… You ask yourself, why fly to California? Of course you go to Santa Monica Beach and get Chinese food or whatever. [Laughs.] But the tradition and the reverence with which they play Dvořák in Prague is more my thing. The U.S. has wonderful orchestras, like Boston and Cleveland. But it’s a completely different way of making music. You always have to have a thick sound; you have to sound like a trumpet.

People you’d like to play with?

I would have loved to have played with Arcadi Volodos at some point, because he has an unbelievably refined sound—comparable to Radu Lupu’s—that would probably blend fantastically with a string instrument. I also like him a lot as a person. But I accept and appreciate the fact that he works extremely carefully and only releases a CD every four years or so. Why should he record with a violinist? Besides him? I’m actually pretty satisfied with my life. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.