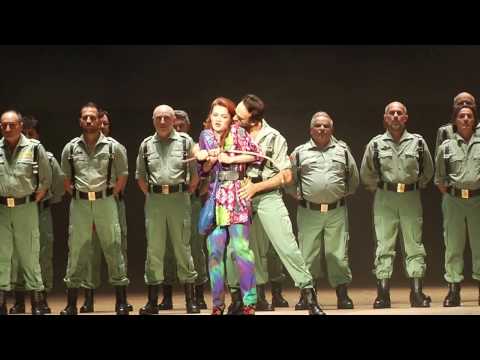

Calixto Bieito is responsible for some of the most indelible images in recent memory on the European opera stage. I’ll never forget his version of “Die Entführung aus dem Serail” at the Komische Oper Berlin. Mozart’s music and the contemporary brothel setting rubbed off unsettlingly on one another—the composition acquired a layer of mysterious grime, while the setting gained a hard-to-place nobility, and the omnipresent, flaccid penis of the singer playing Osmin swung between a blunt statement of fact and a titillation. Bieito is currently preparing for his new production of Verdi’s “I Vespri Siciliani” at the Zurich Opera, premiering June 9. I spoke with him via Zoom about fluidity in rehearsal, ignoring the audience, and the difference between art and culture.

VAN: Right now you’re staging a new production of “I Vespri Siciliani” at the Zurich Opera. How’s it going?

Calixto Bieito: This project was [planned] before COVID; we had a year, and I was very well prepared. Now we’re doing it. There’s a lot on my mind. The themes are very strong, which is good. The dramaturgy and structure of the piece is not perfect of course, because Verdi changed it so many times, but the music, the characters, and the story are wonderful. It’s about myths: the Rape of the Sabine Women, this foundational myth of the Roman Empire. Nationalism, what it means to be a patriot, the relationship between a father and a son. Verdi used the piece to talk about private things, but also about the context in which he lived—the unification of Italy, and the censorship he had to overcome.

Vesper is a strong word because it has many meanings. Of course the evening mass. But also the sunset, the moment when you are going to sleep, or are half asleep, or daydreaming. The word “crepuscular” comes up a lot in the piece too. It comes from the Latin creper. Crepuscular means, of course, the decline of the sun, the decline of a people, a society. It means the moment when you don’t know if you are dreaming or awake.

You’ve described your preparation process as a combination of the intuitive and the academic, involving walks and books. How important is the score in that process?

I mean, I know it by heart. And of course the text as well. But [I know the score by heart] in all the operas I do, including new operas with composers. It’s normal.

Maybe for you—I’m not sure all opera directors know the score by heart.

Yeah, come on, it’s normal for directors. I know the score, I know the words. But sometimes I [purposefully try to] forget because the weight of the tradition makes you create walls in your mind. I try to be creative every day. I don’t go [to rehearsal] with my book, where it says what I have to do each day. I try to paint or to play tennis with the cast. We paint together. It’s nice to work like this—I think it’s very beautiful. We don’t need walls, we need [to be] fluid, like water.

Is that difficult to achieve in opera houses, which often have strict hierarchies—a lot of walls?

I try. I think I’ve succeeded a lot of times.

I’d agree, based on the performances I’ve seen. Obviously I can’t see rehearsals.

[Rehearsals are] very private for me, and for the people I’m working with.

When I say I don’t think about the audience, I cannot think of the audience, because if I’m thinking about the audience and working in so many different countries… I’ve been working since I was super young, in so many different countries. I did one thing in London and it was a catastrophe, and then I did it two months later in Dublin, and I won all the prizes that year. I was like, “Oh my God, what? Sorry, what?” I didn’t understand anything. If I think about the audience I’ll go crazy.

Have you ever gone back to see one of your stagings after the premiere, once the piece has entered the house’s repertoire?

Yes. Not often. I’m not a control freak, I know what I did is going to be changed. I can’t be a control freak; things change in opera. Normally when I go I’m quite happy that they change things. Of course, sometimes they change so many things. But I try to be positive, and if something is terrible, I try to say, “Please don’t change so much.”

Do you enjoy life in Basel?

I love living there. It’s discreet, simple. I love walking by the river. I was born near a river, it relaxes me a lot. I love [the commencement speech] “This Is Water” by David Foster Wallace, or I liked it very much when I read it. I did “Tristan und Isolde” in Vienna [in 2022], and I was thinking about fish and water and human beings and love. I’ll read it again.

In a 2013 interview, you said, “I have to take care not to drown in pessimism.” Is that still true?

My character can be pessimistic. I try to combine optimism and pessimism. In rehearsal I’m normally very, very happy. You have to try to find a balance. I say that, and in my mind I’m very extreme. My mind is very anarchist, very extreme. But I keep it to myself; I can’t put it on other people. I try to be like a river.

I have strong memories of your “Entführung aus dem Serail,” which I saw at the Komische Oper many years after the premiere. The piece was set in a contemporary brothel and featured lots of nudity and explicitly sexual scenes.

“Entführung aus dem Serail” was a fantastic experience. Very hard, I have to confess now. But I was not conscious [of it at the time]. That was better.

Why hard?

I remember the orchestra had a meeting with me, they wanted to talk to me about what I did. They were very aggressive. I don’t like violence at all, I’m completely afraid of violence. Still, it was a wonderful experience. Thanks to: Maria Bengtsson, all the singers, Guntbert [Warns], the actor, all the gogo girls, who were real gogo girls, of course the trust of the house.

I was not conscious of what I was doing, but I knew what I wanted to say: [to show] real romantic love between a pimp and his sexual slave, but he falls seriously in love. That’s why he commits suicide. That’s why I used text from “Last Tango in Paris.” Nobody remembers the librettist for “Entführung.”

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

I definitely don’t.

Me neither. I thought, what is the strongest love story I’ve ever seen? I saw “Last Tango in Paris” when I was 14, I think. At that time [after the Franco dictatorship], you could go to the cinema in Spain without identification. I went to see “Last Tango in Paris” because I thought it was an erotic movie. But it was not erotic. I was super sad when I finished the movie. And then when I was in Berlin, I remembered the text.

You’ve said a few times that when you stage in opera, you don’t have a thesis. You want the audience to have its own interpretation…

…because it’s impossible. I don’t have a message, but of course I have my thoughts, my emotions, what I want and need to express. But I cannot put my thoughts to the audience in the form of a message. I think the difference between art and culture [is that] art comes from dreams, fantasies, the imagination, freedom, political repression… and culture is when the community accepts art as a part of itself.

Art can even come from hate sometimes. Not for me, but some artists [can create] from hate. Imagine, van Gogh died thinking he was a shitty painter.

In 2016, you were supposed to have a staging at the Metropolitan Opera—of “Forza del Destino”—but it was canceled. Have you been invited back to do a new staging there?

Oh, no. They canceled five productions, including mine. I don’t know why, but it’s OK.

Do you want to work in the Metropolitan Opera? It’s one of the most conservative houses in the world.

I want to work if I have normal conditions to make art. OK, this is not the right sentence—it sounds too big. But: normal conditions, [enough] rehearsals. I don’t need eight weeks or something, but [it shouldn’t be] just a cash machine.

I don’t care if it’s prestigious or not. I’m not ambitious, you know? Maybe [the Met] is not my place. I don’t have to be everywhere. I have enough to do. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.