“It’s a bit of a shame that there is no confrontation anymore,” Nuria Schoenberg Nono reflected in an interview with Wolfgang Schaufler, a publisher at Vienna’s Universal Edition. “Everything is in order today; [audiences] only have enthusiasm for the great interpreters, and that is right—but the music itself often has little or nothing to do with its success; the music is much less important in terms of audience response.”

I wonder what Nuria makes of pop music’s antics today, where throwing bracelets, brie, and bras at unsuspecting stars is the rebellious act du jour. Perhaps she was the person who emitted the lone, loud cry of “that’s rubbish” at the conclusion of Gerald Barry’s recent BBC Proms commission, “Kafka’s Earplugs.” Yet she has a point. Part of me yearns for the days of immediately certain audience reactions, where an audience applauds heartily, or boos vociferously, rather than various flavors of demur clapping.

Who might have caused this standardized fragility in audience reactions? Perhaps one answer lies with Nuria’s father. Harvey Sachs’s book Schoenberg: Why He Matters describes the rigorous standards upheld by the Verein für Musikalische Privataufführungen (the Society for Private Musical Performances, a group set up in 1918 by Schoenberg, Alban Berg, Anton Webern, and Eduard Steuermann for the performance of new work). Attendance was only open to members presenting photo identification, “no audible expressions of either enthusiasm or dislike would be made,” press was forbidden, and no one was allowed to publish an account of the concert.

To shut performances away from public view so comprehensively is hardly a confident gesture, but it’s one revealing of the difference between confidence and self-belief, a distinction that animates Schoenberg’s story. “Schoenberg would see himself as a lonely David using his slingshot to fend off hordes of cultural Philistines who were incapable of grasping, or unwilling to grasp, the beauty and the importance of his work,” Sachs notes. It’s a number of cake-and-eat-it moments that Sachs teases out, and unlike previous books discussed in Pages Turned, which amass such “ands” into a view of the subject that’s overly fragmented, Sachs identifies this as the animating tension of Schoenberg’s psyche: a man convinced of his own world-historical importance, yet fearful of public reaction; terrified of death, but satisfied nonetheless that history would be kind.

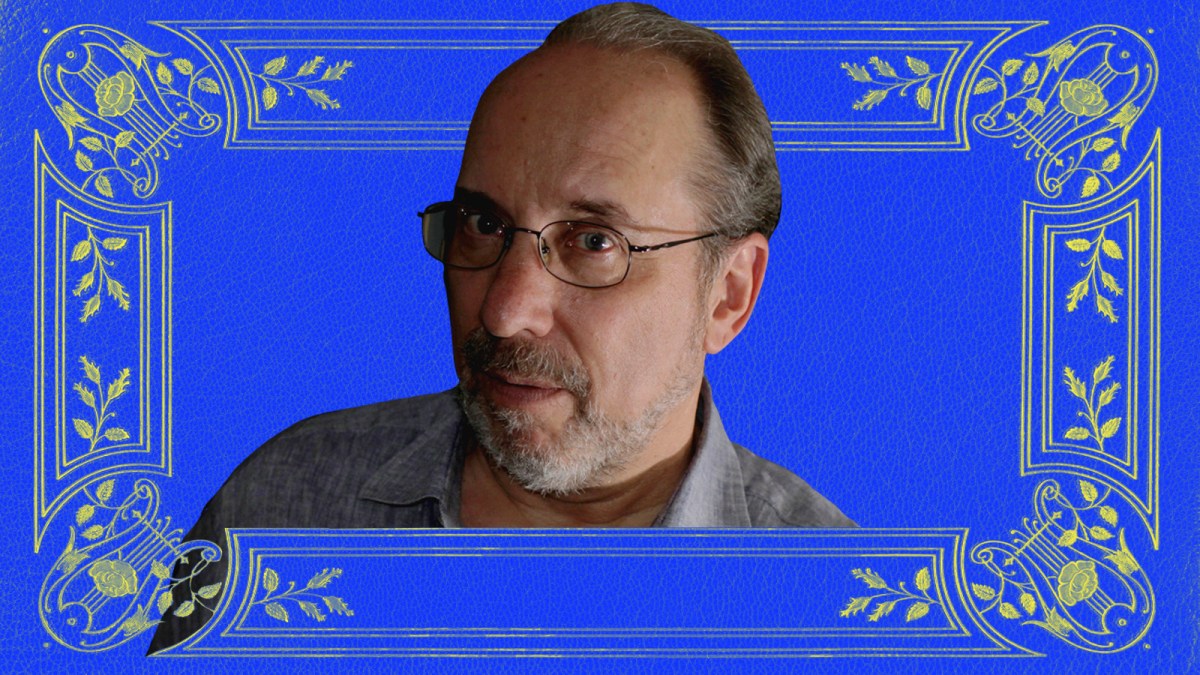

Has it been? Sachs identifies as neither Schoenbergian nor anti-Schoenbergian, but rather “Schoenberg-curious,” a position that reflects up the general feeling around the composer today, where card-carrying ultras opt for Stockhausen, Boulez, and Webern, but rarely Schoenberg. At 77, and after a lifetime of writing books like Toscanini: Musician of Conscience and The Ninth: Beethoven and the World in 1824, Sachs notes the shock at the direction which his curiosity has taken him in, but a development like this makes sense. Schoenberg has had many biographers (as recent as 2019, by Mark Berry), and is yet still unable to properly pierce the mainstream as a composer, existing in the public imagination as a historical harbinger above all else.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

2024 sees the 150th anniversary of Schoenberg’s birth, which perhaps prompted Sachs’s much-needed accessible guide. But, following Nuria’s lead, Schoenberg: Why He Matters is best understood as a confrontation, rather than the defense the title suggests. In fact, Sachs relishes taking chunks out of his subject. “Verklärte Nacht,” which he describes as “Siegfried’s Funeral March” meets the “New World Symphony,” “betrays an emotionally adolescent quality”; though one of Schoenberg’s most frequently performed works, it’s “not one of his most accomplished ones,” he writes, topping off a couple of pretty bold takes. It’s entertainingly catty at times, though it does make you wonder what exactly Sachs is looking for, and whether he’ll ever find it in Schoenberg.

By design, the book is short on musical analysis, but long on context, and heavy on criticism. Where Sachs is most scathing is in the philosophical underpinnings of Schoenberg’s works. “Il Trovatore” is a model of clarity, Sachs writes, in comparison to the libretto of Schoenberg’s oratorio “Die Jakobsleiter,” “a self-flagellating and self-justifying, mystical and pseudo-mystical, philosophical and pseudo-philosophical, verbose, prayerful, doubting, prosaic-poetic lecture-sermon of a text,” where comprehension of German “might be more of a hindrance than a help.” Ouch.

Some of the most telling judgements exist to introduce the people sidelined in sacrifice to Schoenberg’s significant ego. Through “Die glückliche Hand,” Schoenberg’s “Drama mit Musik” from 1910, Sachs traces the difficult marriage to Mathilde, and the tragic case of artist Richard Gerstl, whose affair with Schoenberg’s wife lead to ostracization by the Schoenberg circle upon its discovery, followed by Gerstl’s suicide. Sachs’s reading of the work is an extremely biographical one, with good reason. Linking Schoenberg’s thinking at the time of composition (between 1910 and 1913) to the work of August Strindberg, “Die glückliche Hand” “is unforgiving to the point of misogyny,” as Schoenberg’s self-penned text offers both a manifesto for genius-artists spurned by humanity, and a depiction of women as selfish and small-minded. “The story does not redound to its author’s glory,” Sachs notes, as he continues painting a distinctly unflattering portrait of unbridled ego.

The book’s most important aim is to complicate Schoenberg’s standing in music history. The idea of Schoenberg as some kind of radical iconoclast still persists in conservative musical circles, and, while the works themselves might have been revolutionary, and his teaching encouraged some of the most radical talents of the century, his own view was almost the opposite: convinced (again) of his own historical importance, he firmly believed his art was a continuation of the thin, distinctly Germanic arc of musical history. “Whenever I think about music, I never visualize—consciously or subconsciously—any other than German music,” Schoenberg told his pupil Josef Rufer. In 1921, in conversation with Rufer again, Schoenberg informed him of his breakthrough: “Today I succeeded in something by which I have assured the dominance of German music for the next century.”

Clearly, that didn’t happen, and the reasons as to why are the point at which Sachs’s vehicle hits some predictable bumps. In the final chapter, entitled “What Now?”, this otherwise lyrical and focused book becomes discursive, running through the various established arguments as to why post-tonal music didn’t catch on: unwhistleable; a preserve of the—usually American—academy; the—flimsy—idea that it’s acoustically unsuitable for the human ear; that it sounds like artifice over natural evolution; that it’s unexpressive, or that audiences haven’t found the means to be affected by it. It’s noticeable that Sachs doesn’t do much to refute these age-old criticisms: “perhaps we have reached the end of one great, centuries-long cycle of individualistic European art music,” he muses, after informing us that post-post-tonal music “doesn’t stick.” He needs a good dose of beautiful serialism in his life as a necessary corrective.

Sachs’s confrontations are best aimed at subjects over trends, and when they’re arrow-straight, this method really works, both as a text and as a useful model for approaching the great-man stories of music history today: by being critical to the point of hostility throughout. Schoenberg needs neither flattery nor championing. A detailed interrogation is a better match for the man.

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.