Listen, none of us made good decisions in our 20s. Among the more anodyne of my offenses was that, for about a year or so at the start of that decade, my soundtrack of choice for amorous congress was “Má vlast.” I was clinging to the last Romantic edges of my late-teenage years, and in a way, Bedřich Smetana’s 80-minute sextet of symphonic poems provided an interesting control for an informal, Kinsey-esque experiment: Most of my male partners were done long before the end of the work’s most famous movement, “Vltava.” My female partners generally held out for a few more movements. Make of that data what you will.

Subsequent trips to Czechia since that period of grandiose horizontal refreshment have reminded me of why this was an ill-chosen soundtrack: The “Vltava” melody is used whenever a Czech Airlines flight touches down. It’s scratched out by busking violinists in tourist areas. Despite my specific request that it be omitted from the program, it was played at my wedding on the organ in Prague’s Old Town Hall. It’s a piece of music that has almost become autonomous, not requiring a human being’s performance to bring it to life. (Terrence Malick didn’t help matters, either.) Yet our perception of it is often narrowed in on its first two movements—“Vltava,” preceded by “Vyšehrad.” The rest of it peters out from there. Reviewing a rare performance of the work in its entirety for the New York Times in 1975, Harold C. Schonberg wrote:

“Má Vlast” demonstrates Smetana at his best and worst. At his best, as in “Vlatava” [sic] (or “Die Moldau,” to give it its more familiar name), he is tuneful, original and full of evocations of his country. At his worst, as in the movie‐music sections of “Tabor” or “Sarka,” there is a thudding, heavy kind of outdated romantic rhetoric. Construction never was Smetana’s strong point, and when he ran out of melodic ideas, he was apt to resort to filler material.

This attitude hasn’t changed much in the ensuing 50 years. Full performances of “Má vlast” are still rare, especially outside of Czech orchestras. Preparing to conduct the work with the Munich Philharmonic in 2019, Semyon Bychkov found himself rehearsing with a group of musicians for whom the work was brand new. “I could see that they were thinking, ‘Oh, Smetana…beautiful melodies…,’ And it is not only musicians, but people in general who think that way about this music,” Bychkov told the in-house magazine of the Czech Philharmonic. “But that is very superficial.” Even in Czechia, “Má vlast” isn’t without its historical, at times national baggage. “In secure times, its meaning seems almost like a burden,” conductor Jakub Hrůša told VAN in 2017. “But at times when the Czech people feel something politically is really rotten, it becomes a symbol of cultural identity.”

Even in his own time, Smetana’s music was used as a salvo in the struggle for Czech sovereignty. It gained a renewed charge through the course of the 20th century. Several months after the Munich Pact handed Czechoslovakia over to the Nazis, Václav Talich led a performance of the work at Prague’s National Theater in protest. It eventually cost Talich his job, and led to the German forces banning the work outright (imagine, being that offended by a river). It was likewise a musical rallying cry during the 1968 Prague Spring and the Velvet Revolution of 1989—which led to the overthrow of communist rule in Czechoslovakia. In fact, Bychkov’s new recording of the work with the Czech Philharmonic was made to commemorate the latter.

However, as musicologist Kelly St. Pierre points out in Bedřich Smetana: Myth, Music, and Propaganda, these moments of cultural identity are only so cohesive. Performances of the work as a symbol of resistance and victory against Nazi forces, St. Pierre notes, would have taken place against the backdrop of the Czechoslovak government’s larger move to deport ethnic Germans and Hungarians from the country, a mass forced migration that led to events like the Ústí Massacre and Brno death march. “Such human rights violations, especially under Soviet rule, also reversed understandings of the composer’s usefulness, transforming his myth from an expression of humanity to a tool for and sometimes a symbol of its oppression,” writes St. Pierre, who adds that, following the fall of communism, the composer was “so enmeshed in propagandist work that he became part of a legacy to shed in the interests of reestablishing a new Czechoslovak Republic, not necessarily a topic of celebration or inquiry.”

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

During the Oscars this past weekend, director Jonathan Glazer took to the stage of the Dolby Theatre to receive the Best International Feature Film award for “The Zone of Interest,” his oblique adaptation of Martin Amis’s Auschwitz-set novel. Holding a sheet of paper and speaking on behalf of himself and producer James Wilson, Glazer said: “Right now, we stand here as men who refute their Jewishness and the Holocaust being hijacked by an occupation which has led to conflict for so many innocent people.” Unsurprisingly, many people were quick to ignore the words that followed after “Jewishness” and twist Glazer’s statement into an abdication of his heritage.

In a similar sense, it seems to me writing off “Má vlast” as two good movements followed by four forgettable ones likewise castrates the meaning of the work, and while the comparison may seem uneven—likening the willful misunderstanding of a politically-charged Oscars speech to the truncating of a symphonic poem—that enmeshing of art into propaganda that St. Pierre alludes to is a common factor in both instances. “Má vlast” is an epic experience by design. Smetana spent half a decade crafting the work’s six symphonic poems, the shortest of the set still exceeds ten minutes in length, and the final two movements—meant to be played attacca—total nearly 30 minutes alone. Though Smetana had no interest in ever meeting Wagner personally, he was a fan of his music, even seeing “Die Walküre” three times while on a trip to Munich. It’s not hard to spot the creative fingerprints that “Das Rheingold” left on “Vltava,” but what if the “Ring” Cycle ended after this first installment? What message are we left with? Confining “Má vlast” to the fallen grandeur of “Vyšehrad” and the languid beauty of “Vltava” may be an easier sell for audiences, but it undercuts the real meaning that Smetana puts into the work—particularly in those “thudding” movements of “Šárka” and “Tabór” (with the latter’s seamless flow into “Blaník”).

It’s ironic that Schonberg calls these movements out as “filler material,” because they in fact provide the work’s structural integrity. Without them, “Vyšehrad” and “Vltava” are easily coopted as propaganda. As Kaitlin Lee Ericson writes, these first two movements provide “glimpses of the public face of Czech culture—a composed public image and persona of Czech identity as might be presented to outsiders: foreigners, tourists, representatives of the Empire.” The UNESCO-esque landscape they chart is a castle, once built in glory, now sitting as a Byronic relic of history, and the river that unites the country.

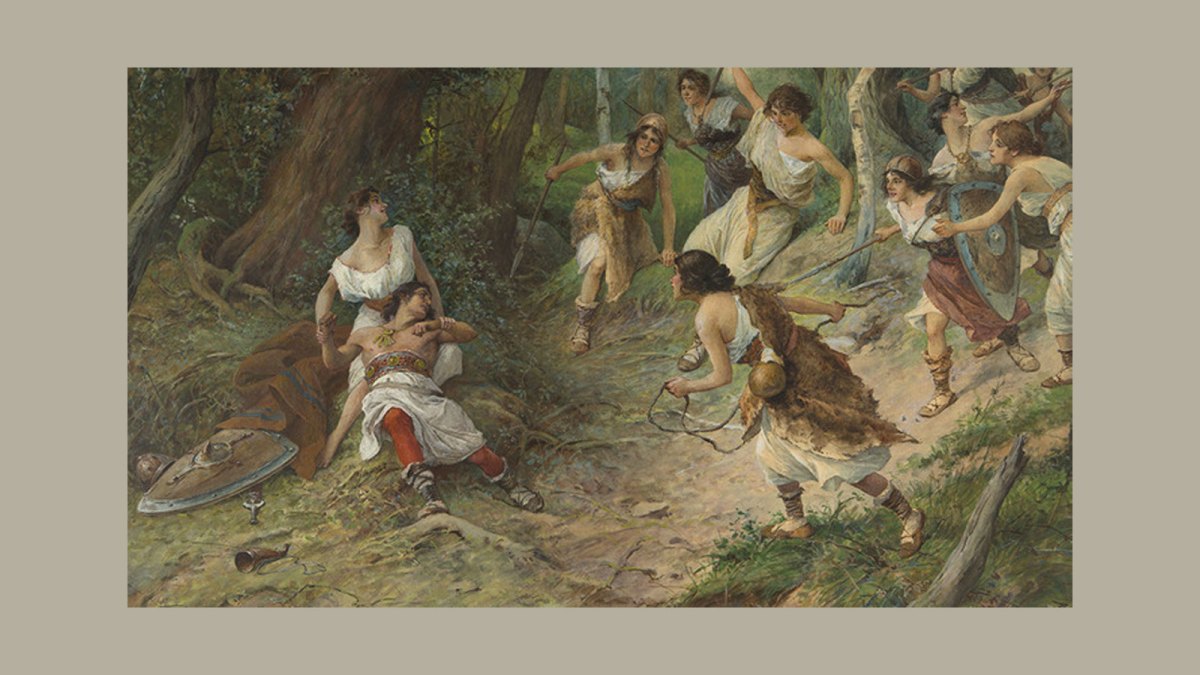

“Šárka” forms a critical turning point. Based on the Czech legend of a successful female army’s uprising against their male oppressors, the third movement opens with the in media res fervor of “Die Walküre”’s second act. Its flow, similar to the long-haul ballets of French grand opera, seems like a lost suite from an opera never written. Paired with the following “Z českých luhů a hájů” (“From Bohemia’s Fields and Groves”), we get a feminine counterpart to the masculine projection, Ericson points out, “unearthing private, even hidden aspects of Czech identity that the first two movements aim to conceal…an inward glimpse into the struggle of Czech identity, including the darker, more violent emotions that must be continually stifled and kept from the public.” “Šárka” is messy, all id to “Vyšehrad”’s superego, but that is just as—if not even more—revealing of the country that Smetana was portraying.

What happens in the final two movements—the pairing of “Tabór” and “Blaník”—serves, as Ericson puts it, as a synthesis to the first two pairings that merges the mythological with the natural: In Tabór, we meet the Hussite soldiers (so named for their allegiance to Jan Hus, a 14th/15th-century leader of the Bohemian Reformation) on their home turf, with a movement dominated by the Hussite hymn “Ktož jsú boží bojovníci” (“Ye who are warriors of God”). The hymn is repeated through “Blaník,” which charts the army’s retreat to Blaník mountain, where they wait in exile to be called to fight for—and win—the glory and freedom of their homeland. That victory is revealed to pan out with the first four-note motif of “Vyšehrad” rising like a phoenix after lying dormant for four movements and interweaving with the Hussite hymn. Whatever we see of Vyšehrad Castle in the first movement, before anything else has unfolded, is deepened and enriched through this callback; we are able to see both the beauty and the bloodshed.

Despite Smetana’s love of his own Czechness, I have to think this is what he wanted us to see: a landscape beyond nationalism and propaganda. He was a composer who, at 24, fought in the Prague June uprising in 1848, part of a long-simmering Czech rebellion against Germanic Habsburg rule. It remained one of the composer’s biggest regrets that his first language was German, and he struggled to learn his national language for most of his life (his initial operas betraying his lack of fluency with incorrect accents on the Czech-language libretti). His love of homeland was stoked further in the 1850s, when he relocated to Göteborg, Sweden, a move that was likely half-financial and half-political. “Shall I—and when—see those dear, beloved mountains again? And with what feelings? My heart is heavy every time I take leave of these places,” a homesick Smetana wrote in his diary in September, 1860. “Be happy, my homeland, which I love above all; my beautiful, my great, my only homeland! I would gladly rest in your lap. Your soil is sacred to me.”

These sentiments are deeply felt in “Má vlast,” one of the culminations of Smetana’s career and his dedication to fostering an environment in which genuinely Czech music could flourish. But he also remained on the periphery of the frontlines for the Czech fight for statehood, knowing that a Czech national music could not exist independently from the politics of his time. His diaries and letters document this struggle over the decades. “Persecution of the Czech opposition has reached its height,” he wrote in 1868. “Salaries are a mockery, and not only journalists are arrested but anyone who so far forgets himself as to speak openly against the rule of the present German Beust-Auersperg Cabinet.”

“The same old misery in political life,” he wrote the following year. “The state of emergency continues, though why, nobody knows, except perhaps their Excellencies, the Ministers. Vienna is the ruin of Prague.” A few weeks later: “The state of emergency has been lifted. Everything is as before, for it was quite unnecessary and simply an act of ministerial revenge.” Six months after that: “Things have taken a turn in favor of the Czechs in Vienna as a result of the elections. They want to balance matters. We have only one answer: ‘State sovereignty for the Czech Crown!’”

He didn’t keep these thoughts to himself, either: “You know what a hard struggle our nation is having to wage for its sealed and sacred rights, sovereign rights for its crown, with the present government, a government which would so dearly like to throw all the nations of Austria into one pot—that of Germanization—in order to rule over all of them with beaucoup de plaisir,” he wrote to Moravian cellist and composer František Neruda. “Praise be to God, our nation fights back uncowed and as one man. All of us, in Bohemia as in Moravia, 5 million Czechs. Victory will and must be ours and soon. Until then let each one stay at his post wherever he is, for now, during the struggle, the muses are silent and Prague is unhappily a site of struggle where nothing but struggle is known at present.”

I have to imagine he found some comfort in setting the Hussite Hymn, with lines that reflected the current fight for Czech independence: “The Lord commandeth you not to fear those who harm the body, and commandeth you to even put your life down for the love of your brothers.…Since ages past Czechs have said and had proverbs which state that if the leader is good, so too is the journey.” Through the historical lens, he’s able to conceal the contemporary struggles for Czech self-determination, hiding them in plain sight among the ruling powers (something he did in many of his operas as well). What’s more, at least in “Má vlast,” he’s able to resolve these struggles, and offer a victory. What the final two movements in particular seem to be telling us is a sentiment that I’ve seen echoed a lot over the last five months: Land you have to kill for isn’t yours; land you have to die for is. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.