On July 11, a public inquiry in the UK heard that the funeral of Cornelius Cardew, and a memorial event held in his memory, were both attended by an undercover police officer deployed by a specialist police unit to infiltrate revolutionary communist groups. Though it was conveyed to him through a manager at the Special Demonstration Squad, a branch of the Metropolitan Police, the witness said that the request to attend the funeral came from the Security Service, MI5.

The Undercover Policing Inquiry is a long-running public inquiry into the conduct of police spies. So far, the inquiry has heard that, between 1968 and at least 2010, more than 1,000 political groups were spied on, and also that between 1970 and 2010, at least 20 spies are known to have engaged in sexual relationships with women without disclosing their identities.

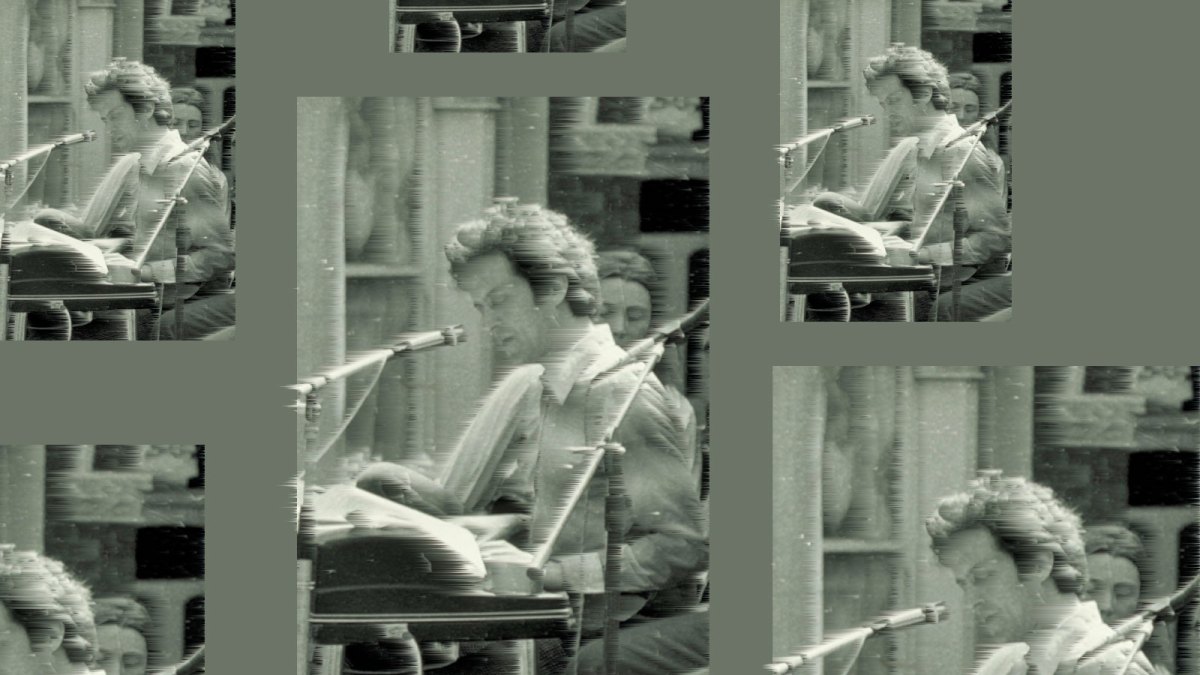

Witness HN19—cover name “Malcolm Shearing”—was deployed by the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) for four years in the 1980s, mainly to report on the Revolutionary Communist Party of Britain (Marxist-Leninist) (RCPBML), of which Cardew, a composer turned political activist, was a co-founder.

In a witness statement, Shearing, whose real name is restricted, said that, in 1981, he had been “asked to attend the funeral of a leading comrade in RCPBML.” He confirmed at the hearing that this comrade was Cardew.

Rather than an instruction from the SDS managers, Shearing believed that the request to attend was made by the Security Service. Though he didn’t recall seeing any documentation, he did remember a conversation he had with an SDS manager, which Shearing paraphrased as: “the Security Service has rung over and wants to know if there’s any chance of you going to the funeral.” Shearing then said that he was also invited to the funeral by Tom Graham, Shearing’s mentor within the party.

Asked what the purpose of him attending Cardew’s funeral was, Shearing replied that he “wasn’t entirely easy” about it. “It may seem ghoulish,” he said, but added that it might have been of interest for the police to know of “people of significance from the past” who were attending.

Later, in January 1982, Shearing was invited by Graham to attend a memorial meeting dedicated to the composer. The inquiry heard that a large part of the evening was taken up by performances: of Cardew’s songs by the People’s Cultural Association (an associated performance group), and of Cardew’s piano compositions by John Tilbury, a longtime friend who would later write an 1000-page biography of Cardew.

When asked why he attended the concert, Shearing confirmed that he would go to events that were outside the scope of political intelligence gathering. He said that “drawing the line between those that I absolutely had to attend and those that were discretionary was not an easy task.”

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

Shearing later submitted a report from the memorial, noting the presence of musicians including Tilbury and guitarist Keith Rowe as well as those who had read poems at the event. When asked why he submitted a report from this event to his superiors, he said, “Out of completeness. With the benefit of hindsight, it might seem a bit pointless. But it was generally considered that events on the fringe like that should have been reported.”

Cardew, born in Gloucestershire in 1936, was a prodigiously talented performer who gave the British premiere of Boulez’s “Structures 1A,” and who learned guitar to perform “Le marteau sans maître” in its first British performance in 1957. He later studied with Stockhausen, who took Cardew on as an assistant on his piece for orchestras, “Carré.”

Through the 1960s, he became gradually more involved in indeterminate music-making, from being exposed to Cage and Tudor in America, through to joining free improvisation group AMM. He composed his landmark “Treatise,” a sprawling collection of dynamic graphic scores for any instruments, between 1963 and 1967. Cardew later dramatically renounced all these kinds of musical activities, in a turn towards both brash tonality and hardline revolutionary politics influenced by Mao Zedong.

Cardew was killed in a hit-and-run accident in Leyton, east London, on December 13, 1981. The coroner reported accidental death, but the cause of Cardew’s death has long been speculated about by those close to him. In Cornelius Cardew—A Life Unfinished, Tilbury writes that the theory Cardew was killed because of his prominent Marxist-Leninist involvement “cannot be ruled out.” ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.