Inevitably, many of the German obituaries for Grace Bumbry—who died on May 7 at the age of 86—have led with the phrase “Die schwarze Venus,” a reference to her barrier-breaking debut in Bayreuth early in her career. This is understandable (headlines only run so long), but also a shame: It reduces a decades-long career that saw the diva move between mezzo and soprano repertoire, covering everything from Glück to Strauss, to a single moment (albeit one with major historical and cultural ramifications). She was far more than “the Black Venus,” and often took pains to ensure that she was the one authoring her career. It’s a shame she never wrote a memoir, but hopefully we can count on gracebumbry.com staying online.

Camille Saint-Saëns: “Mon coeur s’ouvre à ta voix” (“Samson et Dalila,” 1877)

A precursor to the Met’s National Council Auditions, the radio-based Metropolitan Opera Auditions on the Air helped to launch the careers of singers who would become regulars on the company roster, including Robert Merrill, Regina Resnik, and Martina Arroyo—a co-winner with Bumbry in 1958. Despite being just 21, Bumbry’s voice in this broadcast of her Audition already has her trademarks on display: an agility between the mezzo and soprano ranges, a warm bronzed tone, and the ability to shape phrases like Michelangelo working with a block of Carrara marble.

Giuseppe Verdi: “Ohimè! Morir mi sento” (“Aida,” 1871)

Bumbry wouldn’t make her Met debut until 1965. However, her Met Audition win would see her career rise, with an early peak coming two years later with her 1960 debut at the Opéra National de Paris as Amneris, an audition facilitated by Jacqueline Kennedy. At the time, Bumbry was torn between singing soprano and mezzo-soprano repertoire, with her teacher, tenor Armand Tokatyan, advocating for the latter and her coach, Lotte Lehmann, for the former. The end result is that Bumbry is one of the rare singers to have performed both the roles of Amneris and Aida.

Richard Wagner: “Geliebter, komm!” (“Tannhäuser,” 1845)

When Bumbry was hired by Wieland Wagner to sing Venus in the festival’s 1961 production of “Tannhäuser,” the first Black singer to perform onstage at the opera house built in Wieland’s grandfather’s image, she immediately became the target of racist protests. “Bumbry ignored them all,” writes Kira Thurman in Singing Like Germans, which opens with this historical moment and continues with Bumbry earning a 30-minute standing ovation after her first performance. This performance set her on the track for superstardom. However, as Thurman notes, this moment of ascension for Bumbry and rehabilitation for Wagner (whose association with the Nazi regime would have been fresh in the minds of many 1961 audiences) was not wholly altruistic or progressive. “The initiative was deeply flawed,” she writes:

In order to disengage from a previous racial order, Wagner and the opera production team ultimately turned to historical myths of deviant Black female sexuality to transform Bumbry into an erotic goddess on stage. Called the “Black Venus” in newspapers and in casual conversation, Bumbry quickly came to symbolize earlier representations of sexualized Black women in European history, from Sara Baartman to Josephine Baker. Bayreuth’s 1961 production illustrates the problems and paradoxes of dislodging a cultural institution from its racist past by relying on historical stereotypes of Black people to do it.

It’s not hard to corroborate this read. Recalling the performance in a 1977 Times profile, George Movshon described the singer as “a gleaming sex-symbol swathed in 20 pounds of gold lamé.” Munich’s Süddeutsche Zeitung referred to her in more sideshow terms as “the fascinating colored Venus.” Thurman adds that the “symbolic significance” of Bumbry’s debut as a herald for a “new” West Germany “could not be shaken,” especially given that, a few weeks after Bumbry’s debut, the Berlin Wall would divide East and West. But it also “takes on new meaning” when considered in the historical context of Black American musicians performing in Germany, one that Thurman devotes the rest of her book to illuminating in detail that does justice to artists like Bumbry. (If you’d prefer a shorter read, Thurman also published an article on Bumbry’s Bayreuth debut.)

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

Richard Strauss: “Ständchen” (1886)

Among the invitations Bumbry received following her Bayreuth debut was one for a rarefied opening: a state dinner at the Kennedy White House in February 1962, the first such event of the season for the Kennedys, and Bumbry’s first major performance in the United States since Bayreuth.

Jackie-O’s personal invitation required some creative coordination with the 25-year-old Bumbry’s engagements in France: She sang a concert in Paris on Sunday, flew to Washington, D.C. on Monday, attended the dinner on Tuesday, and left a few hours later to be in Lyon, where she reprised the role of Venus on Thursday. In between, she sang a recital in the East Room that included Copland’s “Boatman’s Dance,” Duparc’s “L’invitation au Voyage,” Verdi’s “O Don fatale,” and this early Strauss gem.

Verdi: “O Don fatale” (“Don Carlo,” 1867)

The best way I can think of to describe Bumbry’s mezzo is like a glass of Georgian Chinuri wine: amber-hued and autumnal, so crystalline it can verge on salty, with a dead-on balance of acidity and sweetness that is neither scalding nor cloying. It’s an intense experience that engages all of your senses and demands their full attention. Case in point: this recording of “Don Carlo.” As Eboli (the role that would also be her Met debut), Bumbry commands body and soul of the character’s multidimensional morality. She sells Elisabetta out as being secretly in love with Carlo, but that move is motivated by her own anguished, unrequited love for the same man. At face value, it’s easy to write Eboli off as a manipulative bitch, but Bumbry infuses her with pathos and humanity, showing her to be a woman trying to make the most of her situation in a time when women didn’t have full autonomy over their lives and happiness. (Thank god those days are long behind us…)

Verdi: “Nel dì della vittoria – Vieni, t’affretta!” (“Macbeth,” 1847)

Much like Lehmann‘s, Bumbry’s autobiography is, at times, subjective. Opera is here to remind us that the truth often is. In her website bio, Bumbry’s move from mezzo to soprano is styled as a drastic and decisive switch: “Accustomed to making headlines wherever her travels took her, she shocked the opera world once again by changing not only her repertoire but her voice category as well… and the opera world was in an uproar.”

In reality, Bumbry’s transition from mezzo to soprano was a bit more paced. Tokatyan, her champion for the soprano repertoire, died in 1960, which left Bumbry without a fierce advocate for her higher range, or someone to coach her in soprano repertoire. Yet in Bayreuth she sang the Dresden version of Wagner’s opera, which has Venus’s music sitting higher than it does in the Paris version, a decision she felt was related to Wieland Wagner and conductor Karl Böhm both seeing something in her that was “not a typical mezzo.”

Bumbry sang her first soprano role in 1964 as Verdi’s Lady Macbeth for her Vienna Staatsoper debut. Her own reasoning for this was sound: “I simply do what many others in the 19th century did before me. I don’t think singers like Grisi, Pasta, Malibran, and some others ever worried about belonging to a specific category.” Certainly the composers writing for them weren’t worried either. It’s out of the generation of Grisi and Malibran that Verdi stepped, and his early works like “Macbeth” exemplify the female voice as an operatic chameleon: able to capture both elation and pathos, to soar towards the tropopause while remaining indelibly grounded.

Georges Bizet: “L’amour est un oiseaux rebelle” (“Carmen,” 1875)

To read Bizet’s “Carmen” as a story of clashing fates is, as musicologist Susan McClary writes in her Cambridge guide to the work, “to ignore the faultlines of social power that organize” the opera. Some of those faultlines are visible within Bumbry’s own story. An early competition win in her native St. Louis earned Bumbry a $1,000 war bond, but the other prize—a scholarship to the St. Louis Institute of Music—was denied on the basis of her race. She was also routinely sexualized by the press, including after her Bayreuth debut and her first outing in the role of Carmen. Even before the latter, in fact: In advocating for the Met’s Rudolph Bing to cast her in the role, the New Yorker’s Winthrop Sargeant compared Bumbry to Sophia Loren, describing her as “a combination of an urchin and a leopard…an array of God‐given physical and temperamental attributes.”

McClary’s read of “Carmen”—in which the work’s “‘realistic’ treatment of race, class, and gender formed the basis of its initial horrified rejection and also set the terms of its exuberant acceptance the following year”—makes these sorts of endorsements a rich comparative text. Bumbry, who said that the role “fit me like a glove, even though I never really liked her character,” was less interested in the deep reads. “I don’t think about Carmen as a Gypsy,” she told Dennis McGovern for his 1990 collection of opera interviews, I Remember Too Much. “I just think about doing the role and singing the music that Bizet wrote.”

Still, Bumbry continued, “you can give a believable dramatic performance even if you don’t like the character at all.” And she maintained a bit of a Carmen-esque spirit offstage. She dressed as Bizet’s heroine in a promotional campaign for Lamborghini, and was the second person to own a Miura P400. She notes this in her biography, along with the many “furs, designer gowns made by Yves Saint Laurent, Heinz Riva, and Bill Blass, and jewels of the most exquisite quality” that came into her possession. (To quote Lucille Bluth, “good for her.”)

Gaetano Donizetti: “Va infelice e teco reca” (“Anna Bolena,” 1830)

“Grace’s success, to be brutally honest, made me feel insecure, perhaps even afraid. I feared that the ‘powers that be’ would permit only one or two blacks at a time to emerge prominently,” recalled Shirley Verrett in her memoir, I Never Walked Alone. “Here we are, essentially contemporaries (I am a few years older), with the same voice type. What is America going to do now? Trying to get my start, I felt that we would be treated like two black racehorses and the one that ran (or sang) the fastest, in the figurative sense, would cross the finish line first.”

Verrett would continue to feel that “black racehorse mentality” in the early years of her relationship with Bumbry, which began with an awkward introduction and continued with tense encounters that led up to the two singing a joint concert in New York to celebrate Marian Anderson’s “80th” (actually her 85th) birthday. “I have recollections, but I’m not sure I want to divulge them,” Bumbry (in her inimitable raconteur style) told Arthur White of those concerts in a 2020 interview. “I enjoyed working with her, and I enjoyed the competition. I don’t think she saw it in the same line that I did.”

That competition came to a head in the concert with the duet between Donizetti’s Anna Bolena and Giovanna Seymour. According to Bumbry, the extra high Cs started with Verrett. “I decided, if she’s going to put those in there, I’m going to put a couple in there, too.” The result was, in Bumbry’s words, “a shouting match. When I heard it afterwards, I thought, Oh my God, where is the musicianship of these ladies?! They’re just screaming at each other! But Anna Bolena and Jane [Seymour]? That’s what they were. They were competitors.”

Richard Strauss: “Ah! Ich habe deinen Mund geküsst, Jochanaan” (“Salome,” 1905)

“In the history of Covent Garden, they never sold so many binoculars,” Bumbry told People Magazine of her 1971 “Salome” at the Royal Opera House, in which she stripped down to “my jewels and my perfume.” The jewels actually formed a sort of bikini for Bumbry, leaving her exposed in a major way for the era, but not at the level of, say, Karita Mattila’s 2004 performance at the Metropolitan Opera (the fact that we will never get a “True Detective” season with these two woman is unforgivable). This news item appeared in the Times next to an ad for a bikini-clad Claudia Jennings, Playboy’s 1970 Playmate of the Year, in the off-Broadway play “Dark of the Moon,” which tells you everything you need to know about the cultural shift in sexual attitudes of the early 1970s.

As the controversial Camille Paglia writes in the beginning of Sexual Personae, “Society is a system of inherited forms reducing our humiliating passivity to nature. We may alter these forms, slowly or suddenly, but no change in society will change nature.” In this truncated video clip of Bumbry’s Salome, we can see her presage Paglia’s theory. Bumbry’s Salome, with horn-of-Jericho clarity and volume, seems defeated as she claims her kiss from Jochanaan’s severed head. It’s as if she’s realized that her entire gambit against society—a society over which she presides as a royal family member—was built on a foundation of sand. She may have altered the form of this society, but nature has returned to claim her due. Death is not a tragedy for this Salome, but an inevitability.

Giacomo Puccini: “Vissi d’arte” (“Tosca,” 1901)

This particular performance of what would become another signature soprano role for Bumbry was given at the first Kennedy Center Honors ceremony in 1978, with Marian Anderson as one of the honorees. Just over 30 years later, in 2009, Bumbry would receive her own honor. In tribute, Angela Gheorghiu sang the same aria at that ceremony.

Verdi: “Ciel, mio padre!” (“Aida”)

“The main reason that I wanted to sing Aida was because of the scene with Amonasro. It’s the most beautiful, heartrending music in grand opera,” Bumbry said in I Remember Too Much. “I feel what Verdi’s doing with the music, the dynamics, and the text. From day one, I felt if you get a baritone who really feels his oats, it’s sheer heaven. Even when I was doing Amneris, I’d always be present for rehearsals for that act because it fascinated me.”

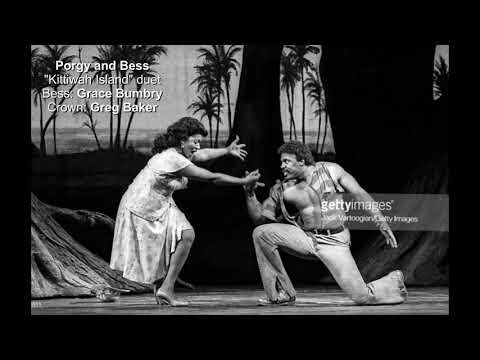

George Gershwin: “Crown!… It’s like this, Crown” (“Porgy and Bess,” 1935)

Last year, the soprano Angel Blue withdrew from her Arena di Verona debut in Verdi’s “La traviata,” owing to the company’s use of blackface in a concurrent production of “Aida.” In a statement posted to her social media, Blue wrote: “I was so looking forward to making my house debut at Arena di Verona singing one of my favorite operas, but I cannot in good conscience associate myself with an institution which continues this practice.”

Among the responses to that statement was one from Bumbry, which expressed “shock” at Blue’s decision. “To be proud of your race is a noble thing, and one which should be honored all the time,” it read in part, “but if you made the choice to perform in a medium of Opera [sic] you must first know the history, and the desire for credibility.” It’s funny to read this comment in the context of the 1985 Metropolitan Opera premiere of “Porgy and Bess” which featured Bumbry as Bess.

She didn’t want to sing the role. “I thought it beneath me,” she said of how she felt at the time. “I felt I had worked far too hard, that we had come far too far to have to retrogress to 1935.” Ultimately, she resolved that the work was a piece of American history and “was still going to be there,” whether she was the one starring in it or not. No biography, subjective or objective, is a straight line of logical opinions. We often hold multiple contradictory views at once, often without explicitly assigning them opposing categories.

And yet, I found Blue’s move to withdraw from Verona to be an incredibly Bumbry-esque one. In it, she took control of the narrative she wanted to have surrounding her career. Bumbry’s response revealed more of the problems and paradoxes that Thurman writes about in Singing Like Germans. It wasn’t up to Bumbry to solve those problems or account for those paradoxes, but rather for us to consider them as part of the broader scope of her career and the legacy she leaves behind. Each generation builds on the last.

Bonus: Verdi: “Fu la sorte dell’armi a tuoi” (“Aida”)

Why pick Aida or Amneris when you can, with a little TV magic, sing both? ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.