Edward Said reigned as the poster child for public intellectuals, having made early waves with his breakout 1978 tract, Orientalism. Just a few weeks after the 20th anniversary of his death from leukemia at the age of 67, his name is being invoked again on all sides of the news cycle. His criticism of both Israel and Arab countries made him a controversial figure in his own time, and served as a bellwether for one of the guiding principles of his life: He lived for counterpoint, tracing his literary theory of contrapuntalism to his love for classical music. He was born in Palestine but grew up in Cairo and eventually settled in New York after an Ivy League education, and was simultaneously at home everywhere and nowhere. For Said, home itself was a polyphonic construct.

It was precisely because of this that he was able to achieve the level of insight into western culture that he did, through criticism that often—as we see in the works below—included classical music.

Johann Sebastian Bach: Aria da Capo from “The Goldberg Variations” (1741)

In Culture & Imperialism, Said uses classical music as a roadmap for decolonizing cultural studies through the metaphor of contrapuntalism: “Various themes play off one another, with only a provisional privilege being given to any particular one,” he writes, adding that the end result, with its manifold voices, still bears “concert and order, an organized interplay that derives from the themes, not from a rigorous melodic or formal principle outside the work.”

Bach’s “Goldberg Variations” are an object lesson in Said’s approach to cultural theory—examining and reexamining every available iteration of a theme, ending as it begins, but with a richer meaning in the repetition. Said was especially fond of Glenn Gould’s first recording of the Variations from 1955, because it “lets you experience the sort of understanding normally the result of reading and thinking, not simply of playing a musical instrument.”

Karlheinz Stockhausen: “Klavierstück X” (1962)

Said himself was a classically-trained pianist, with dreams of making that his profession as a teenager. Even after he shifted focus, he continued to study the instrument while an undergraduate at Princeton, taking lessons at Juilliard. His music criticism often came back to pianists he admired, including Gould and Maurizio Pollini. “You are aware of [Pollini] encountering and learning a piece, playing it supremely well, and then returning his audience to ‘life’ with an enhanced, and shared, understanding of the whole business,” he wrote for Harper’s in 1985, recalling one performance of Stockhausen’s fiendish “Klavierstück X.” In that performance, Said perceived “some of the marginality and playful anguish of the composition itself—music that takes itself to the limits unapproached in the work of other contemporary composers.”

Richard Strauss: “Die ägyptische Helena” (1928)

One of Said’s greatest strengths as a music critic were his writings on opera—which perhaps surpassed his passion for piano literature. He was also at his best when examining imperfect works, citing their flaws and incongruities as features, not bugs. “‘Die ägyptische Helena’ is a vast tissue of anomalies, contradictions, and impossibilities,” he wrote in a review of Santa Fe Opera’s 1986 production of the work. “It is a strangely interesting opera for that reason.”

Works like Richard Strauss and Hugo von Hofmannsthal’s bizarre Helen of Troy fanfic also gave Said a chance to put his other areas of cultural criticism to good use. “Hofmannsthal writes in the preface that Menelas’s morality and sense of guilt made him ‘to me the fatal embodiment of everything occidental, while in [Helena], I saw the inexhaustible strength of the Orient.’ This rather pompous Orientalism is used, I think, to hide the difficulty of getting Menelas to change his mind convincingly, since in most of Act II he is as murderous as he was before drinking the lotus juice at the end of Act I. Even after a fantastic night with Helena, he is still furious enough to kill her.”

Vincenzo Bellini: “O rendetemi la speme” from “I Puritani” (1835)

“What an odd, even kinky spectacle this opera presents, with its interminable vocal acrobatics, its vacant plot, its pointless allusions to seventeenth-century England,” Said wrote in a 1987 article on music and feminism. “At its center stands a fluttery teenager who has gone ‘mad’ in her love for a man she thinks has betrayed her; the lovers’ music is based upon an inhumanely elongated treble melody set above an unabatedly monotonous and minimal bass, punctuated by militaristically concerted brasses. Exhibitionist display, an utterly precious and exhausting idiom, endlessly forestalled climaxes, men’s and women’s voices rising and falling indiscriminately in constant imitation of each other: This surely adds up to a vision of sexuality that requires some skeptical attention, not least for its enduring capacity to captivate large audiences of men and women.”

Anthony Davis: “Bismillah hirrahman-irrahim” from “X: The Life and Times of Malcolm X” (1986)

If you want a nutshell history of opera in the ’80s at Lincoln Center, look no further than Said’s December 6, 1986 column in The Nation, where he reviewed two Met performances—the premiere of Otto Schenk’s “Die Walküre” and the company’s old John Dexter production of “Aida”—plus New York City Opera’s world premiere of Anthony Davis’s “X: The Life and Times of Malcom X.” In this trio, we see the Met as a place where “the avant-garde work of the 19th-century is flattened into a semblance of its conservative counterpart.” City Opera, on the other hand, was a home for operas produced “with some vital conception that informs the whole and with some sense of their own history or their relevance to the history of our time.” Still, Said noted with some apparent sadness that “X” would have a hard road ahead of it, both in terms of selling Malcolm X to typical (read: white) Lincoln Center audiences, and finding singers willing to invest their time in learning the music when there would be comparatively few opportunities to sing it.

It’s illuminating to read Said’s praise of “X” in advance of the work’s Met premiere: his gleeful admiration for an opera he called “uncompromising politically, interesting if not always stylistically coherent in its music”; his wonder that the piece was “put on in these reactionary times”; and the “fertile tension” he locates between Malcolm and the Nation of Islam. He reserves special praise for Malcolm’s second conversion in Mecca, in which Davis layers Malcolm’s jazz-singed inner monologue over a sostenuto of the fatiha coming from the mosque. “Malcolm’s coming to consciousness in Islam is synonymous with his liberation from all the bonds of racial exclusivism,” Said writes. “Malcolm’s solitude and eventual acceptance of Islam’s universalism seems to be influenced by Schoenberg’s ‘Moses und Aron,’ although the divine anger represented by Schoenberg as being in Moses from God is displaced almost unilaterally to Malcolm’s time in history: ‘a tide rises at your back and sweeps you in its path.’”

RIP, Edward Said, you would have hated the WCPE discourse.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

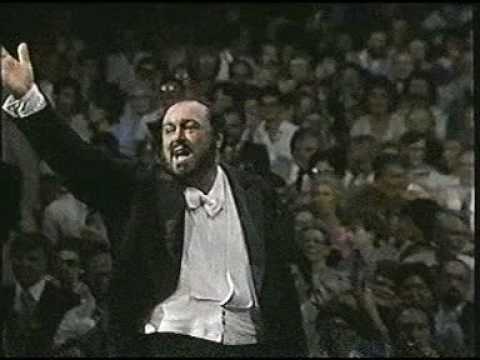

Giacomo Puccini: “Nessun dorma” from “Turandot” (1926)

Said had very little use for Italian opera, in part thanks to its biggest champions in the second half of the 20th century. “The very prominence of a grotesque like Pavarotti is itself an indictment of the repertory that suits him so well. Such singers have reduced opera performance to a minimum of intelligence and a maximum of overpriced noise, in which almost unbelievably low standards of theater combine with equally low standards of musicality and direction.” In fairness to Pav, Said would later have measured praise for the tenor’s performance as the title role of Mozart’s “Idomeneo.”

Gioacchino Rossini: “Semiramide” (1823)

One Italian opera composer who gets a pass from Said is Rossini (though he qualifies this, dryly, one imagines, as everything Rossini except “Il barbiere di Siviglia”). “As a comic genius, Rossini matched drama and music to each other quite perfectly. In the greatest of his serious works, of which ‘Tancredi’ and ‘Semiramide’ are perhaps the preeminent cases, one feels Rossini going through expression, dramatic situation, and character in order to lay bare the core of his musical inventiveness. The result, I think, is a kind of metamusic, music about music, or music largely detached from its social and historical encumbrances.”

Giuseppe Verdi: “Aida” (1871)

“The embarrassment of ‘Aida’ is finally that it is a work not so much about but of imperial domination,” Said wrote in the most thorough of his multiple takedowns of Verdi’s opera. The composer’s own antipathy towards the piece—as an opera, as a commission, and as a subject—didn’t improve “even though during those two years he worked on the opera he kept getting assurances that he was doing something for Egypt on a national level.”

The result is a piece that “embodies, as it was intended to do, the authority of Europe’s vision of Egypt at a particular moment in its nineteenth-century history, a history for which Cairo in the years 1869-71 was an extraordinarily suitable site,” Said writes. In contrast with Rossini’s best works, “Aida” is an opera welded to its social and historical baggage.

Pierre Boulez: “Pli selon pli” (1960)

In line with his disdain towards the Met’s reliance on a flattened 19th-century landscape, Said was wary of “reactionary” composers like Arvo Pärt and Henryk Górecki. His sonic terra firma was Pierre Boulez, “a composer interested in the past as something requiring constant revision, and in constructing the present.” Like Rachmaninoff and Britten, Boulez was a composer, performer, and critic—a one-man musical ecosystem. Like Wagner, he waged an “all-front campaign…to create his own stage, tradition, and critical vocabulary” and make the 20th-century concert its own form, independent of historical routine and ritual, forcing open “the self-satisfied little boxes in which lazy audiences and unenterprising concert organizers have placed classical music, the better perhaps to restrict its genuine force and often disturbing eruptions.”

Boulez’s proficient disruption included an acuity of vision for programming in line with Said’s vision for comparative literature and counterpoint: “There is no question that whether or not one likes or understands works like ‘Pli selon pli,’ they gain in power and intelligibility when experienced in the presence of other 20th-century works that are reactions not only to various Modernist literary texts, but to other attempts to render terror, sorrow, and awe.”

Richard Wagner: “Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg” (1868)

A landmark of Said’s music writings is “The Importance of Being Unfaithful to Wagner,” written for the London Review of Books in 1993. Reviewing a series of books about the composer published that year, Said offers a vision for how we can call out the composer’s “vile ideas” and “despicable pronouncements” as such, while also gelding his specific vision for performance in order to expand his works beyond their antisemitism. Citing Jean-Jacques Nattiez’s quote that “In order to be faithful to Wagner, one has to de-Wagnerise him,” Said refers to Hermann Prey’s performance as Beckmesser in “Meistersinger” as an instance of how Wagner’s works may be reinterpreted and reanimated on contemporary terms. “Rather than the neurotic, black-suited Shylock figure regularly trundled out, someone who barks more often than he sings, Prey’s Beckmesser was a pouty, vaguely adolescent, and extremely vulnerable middle-aged man, using his insecure learning as a shield for his sexual uncertainties.”

Anton Bruckner: Symphony No. 4 (1881)

Romanian conductor Sergiu Celibidache was another artist who, for Said, was at the vanguard of reconceptualizing the concert-going experience in the 20th century. This time, it didn’t matter that his repertoire was from the late Romantic era. (Surely Said must have enjoyed Bruckner’s fetish for polyphony.)

Said saw a 1989 performance of Bruckner’s Fourth given by Celibidache and the Munich Philharmonic at Carnegie Hall. It was the only work on the program, yet Celibidache doubled the hourlong runtime: with “immense” pauses between movements, a slow approach to the podium, and “the courtly and deliberate manner” of curtain calls.

“The point in all this, I think, is to force the boundaries of the performance occasion, and to transform it into something more focused and thought-through,” Said wrote for The Nation. “One has the impression that Celibidache’s is a continuously worked-out performance encompassing and welding together musical and performance duration, and this, I believe, makes for an extraordinarily interesting transfiguration of time.”

John Adams: “Chorus of Exiled Palestinians” from “The Death of Klinghoffer” (1991)

“The paradox is that opera is supposedly the most ‘nonideological’ of all musical genres, yet it is the most manifestly saturated in and directly influenced by politics, history, and social movements,” Said wrote in his review of the U.S. premiere of “The Death of Klinghoffer.” He continued, “A further irony is that the phrase ‘ideological’ indicates politics that the critic happens to disapprove of, whereas a politics that does not trouble The New York Times or The Wall Street Journal is construed as ‘nonideological,’ and consequently never explained or even discussed.”

As both a Palestinian and a cultural critic, Said was in a unique position to cover “Klinghoffer.” He was initially horrified at the idea of an opera being based on the historical event, still fresh in memory; he had been an outspoken critic of Abul Abbas, the leader of the hijacking of the Achille Lauro, along with the “Palestinian desperadoes” like him. “One would have thought an opera about the incident was in a sense ideologically predetermined, especially for American audiences,” Said writes.

Rather than see John Adams and Alice Goodman’s work as a one-sided apologia for terrorism, as many of his fellow critics did at the time, Said encouraged audience to consider it “a frame, a background, a historical and aesthetic envelope for what, in another context, Thomas Hardy called ‘the convergence of the twain.’” Even if he wasn’t wholly convinced by Adams’s score (though he mentioned being personally moved by the opening chorus of Palestinian exiles), he still viewed the work as an essential exercise in counterpoint as a conduit for meaning. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.