Composer Donnacha Dennehy writes music inflected by the overtone harmonies of the French spectralists and the propulsive rhythms of American minimalism, a combination resulting in something all his own. It’s a captivating blend that perceives the hypnotic thread uniting two genres often considered at odds (and whose practitioners were frequently dismissive of one another). I talked to Dennehy, an engaging and self-deprecating speaker, by phone from his home in Princeton, New Jersey—where he’s a professor of music—about revision, the Irish view of the classical canon, and how the fact of death animates his art.

VAN: Your new Violin Concerto, for Augustin Hadelich, is being performed at the Musikfest Berlin on September 7…

Donnacha Dennehy: I’m excited it’s going to be done there. I’m actually coming over for it. I’ve come to all these early performances, because I’ve done tiny revisions in between each one. And now I think I’m done with it. I want to come over and make sure I’m done with it. [Laughs.]

What kind of things are you changing?

We first did it in the fall of 2021 with the Philharmonie Zuidnederland. The second movement got into this whole interior-of-the-sound thing, an overtone thing, and I thought it sort of destabilized the poetic statement. I basically cut a chunk of it out just before the performance, and then I went home and revised it to make it elegant. Then I’ve mainly been carving out the orchestration in the third movement so that the violin is clearer.

It was just done at the Aspen Music Festival; I added an extra bar in the third movement. There was a hint of a reel in it. I think I was hiding it for a while, like, I shouldn’t go there, and then I realized there was no point hiding it.

That seems like a small change that could have a major effect.

Yeah, I’m not covering it up. I’m just going with it.

As you revise the concerto in these small ways, are you also discovering new things about the piece as you keep hearing it live? Does it keep shifting; or can you kind of hold it down, does it get more fixed in place?

It is getting more and more final, thank God. But each time I hear it… In Aspen, there was just one rehearsal and then the concert, but there was a place where the conductor Markus [Stenz] asked the strings alone to do something, and I was like, that’s so much better than what I have with the winds there. I could keep on discovering stuff.

Laurie Anderson has this phrase that compositions are never finished, they’re just abandoned. It’s time for me to abandon this, because I keep on hearing new things. And they can just be for other pieces. Pieces talk to each other. Sometimes when I’m at a loss of what I’m doing in one piece, I hear another piece talking to me and suggesting a way forward.

I’m really desirous of locking [the Violin Concerto] in. But there are more things I hear. And weirdly, no matter how much you mock something up as you’re composing it, there’s something about the experience not only of hearing it in rehearsal, but also of hearing it in concert, that really communicates the point of the piece. Nowadays I’m determined, at least while it’s fresh in my mind, to try and clarify it as much as possible.

When I was flipping through the score, I noticed that the look of the piece was somewhat traditional: there are a lot of fast notes in the solo violin and slower notes in the orchestra, and it’s in a three-movement structure…

Augustin had to talk me into the three-movement structure. There was so much to and fro about that. I had to find a way that the movements would speak to each other. It definitely plays with the scaffolding of the traditional approach.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

How did Hadelich convince you what structure to use? What were those conversations like?

He sent me a whole list of concertos to listen to, like, “Can you imagine these being just one movement?” You know, there was part of me that wanted to take on… I don’t want to sound grand, and it’s a weird feeling as an Irish person too, about tradition: because we don’t really have it coming down. I don’t come from a classical music background. But I wanted to take on the tradition. That’s eventually what turned in me.

In me, it’s a continual battle between a poetic and a structural statement. There’s also a sort of sentimental side to me; I often worry it’ll get too sentimental. I have to have processes to prevent that. There’s this kind of friction between the structural view of music against the poetic view. Part of it was also me wanting to take on these kinds of ground forms, these templates, and do something with them.

What do your processes to prevent things getting too sentimental look like?

I have an obsessive side to me. I get obsessed with details. A part of me gets obsessed with harmony, the interaction between mobile harmony and the harmony inside the sound itself. I will do these processes like palindromes. But there is part of me that wants to say something beautiful all the time. There’s this line from Yeats, he’s talking about the 1916 Easter Rising rebellion: “A terrible beauty is born.” That’s always in my head. I’ve misconstrued it obviously, in lots of ways, but I think of it as a fractured beauty. It has to be filtered through a sieve or something that gives it an interesting friction. That powers a lot of what I do.

In 2006, you interviewed composer James Tenney. In the conversation, he said that spectralism felt too “European” to him: the forms of the pieces were too dramaturgically traditional. Your music also doesn’t sound much like what we usually think of as spectralism. Do you agree with Tenney?

As a teenager, I was super interested in American minimalism. In my head, I even hear a kind of proto-spectral approach in John Adams’s “Common Tones in Simple Time.” Towards the end, Adams stays on these harmonies, and then there are almost like these metric modulations, too. He’s dealing with liminality; he’s playing with it between the speeds and the harmony. That is a stronger kind of spectral influence on me than [Gérard Grisey’s] “Les espaces acoustique” to some extent. I didn’t mean it in a glib way, but I once said that I was really into what the French spectralists—but especially Grisey—were doing with overtones, but I wasn’t interested in the apologetic modernist surface. I don’t see it that way anymore: I believe they really felt that. But it wasn’t for me.

[The spectralists] were rebelling against a kind of modernism, and I think a movement that rebels against another one also takes on what it’s rebelling against. In Ireland, the red British post boxes were the original ones, and they were just painted green.

With Tenney, the idea was about not even getting involved in the pure form, letting it show itself. I can’t be as cool as that. It’s not me. I have to write to what I think is true, but he was writing to what he felt was true, and I really admire that.

You founded the Crash Ensemble in 1997, leading it until 2014, when you moved to the U.S. to teach at Princeton. Do you miss the day-to-day work with an ensemble?

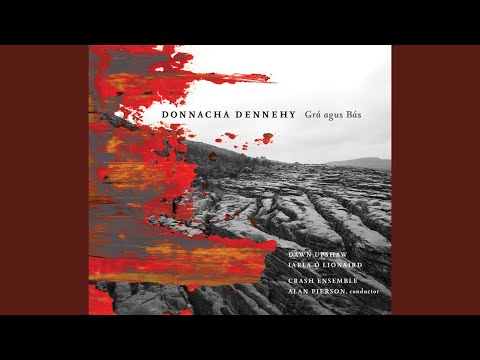

Oh, yeah, I really do miss them. They have been involved in all my operas, so there is that practical connection. It comes and goes; I don’t miss the administrative side of it, although there is an administrative side in teaching too. But I do miss planning concerts. I programmed lots of Murail, Grisey, and early American minimalism when none of that was ever done. You’re finding new stuff all the time and that’s fun.

I was just thinking the other day, Am I going to suddenly just drift away from them? It does fill me with a bit of sadness. It had the feeling of a band, you know? But Kate [Ellis] has been running it for a good 10 years. I’m becoming a hermit now in Princeton among the trees. [Laughs.]

I was surprised reading other interviews with you how regularly and frankly you bring up your preoccupation with death. In one, you said, “I think that all art is about transcending the limits of the world, especially the limit imposed upon us by death.” Does that manifest itself in your music?

Yeah. Well, it is in me. I think it’s what made me be a composer, to be honest. I remember, even as a child, being terrified of death. It’s even kind of an obsessive thing: I had a certain date in my head that I thought I could die on, and then I used to be terrified every time that date would come around. The date is still in my head, so I’m not going to say it.

I’ve always been aware of how precarious this is. My music has always been stalked by the experience of time ebbing away. Structurally, linear time is an obsession with me. It’s about that kind of progress, although you never know when it’s going to happen.

I have a young daughter, and she thinks about it—children think quite seriously about death and the limits put upon us. Being surrounded by trees here in Princeton, I’ve gotten more interested in the seasons, in recurrence and how that’s life-giving. I just wrote a big piece for Alarm Will Sound called “Land of Winter,” which was the classical name for Ireland, that I’m quite proud of. It’s an hour-long piece that goes through the 12 months, and it’s about life changing through the year. But no doubt the biggest influence is in the idea of trying to defy death, of not giving into it.

A surprising number of spectralists—Grisey, Claude Vivier, even the writer Bob Gilmore, who wrote books on Harry Partch and Vivier—died young…

Bob was a dear friend of mine. I was broken when he died. My new studio is just white walls, but in my old studio I had a picture of Bob, looking down on me to make sure I was working hard. He loved music so much, and he invested so much in the way he listened to it. I thought I should have [his picture] to make sure I’m doing as good a job as I possibly can, because there was someone who loved music. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.