The story of musical minimalism has been told many, many times—and for good reason. Emerging from the New York and San Francisco countercultures of the 1960s and quickly becoming an international phenomenon, minimalism’s hypnotic drones and toe-tapping pulses represent the rare avant-garde idiom that is both experimental and popular. Historians of minimalism have typically focused on the pioneering work of four composers, sometimes dubbed the “Big Four”: La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, and Philip Glass. But there were many, many more musicians working in the world of minimalism, and our new book, On Minimalism: Documenting a Musical Movement, which releases this week in Europe, tells their stories by reprinting dozens of rare and out-of-print documents.

In this playlist, we highlight an alternative history of minimalist music, guided by quotations from the documents featured in our book. What does the most important avant-garde movement of our time sound like, when the Big Four aren’t given center stage?

John Coltrane, “Africa” (1961)

“I had a sound that I wanted to hear… And what resulted was about it. I wanted the band to have a drone.” —John Coltrane on “Africa”

Much ink has been spilled about the origins of minimalism: Did it begin it La Monte Young’s 1958 “Trio for Strings” or Terry Riley’s 1964 “In C,” or does it go back much further, to Satie’s “Vexations” or even Wagner’s “Rheingold” prelude? But one thing is clear: minimalism, as we understand it today, emerged when a wide swath of Western experimental improvisers gazed towards India and Africa, and began incorporating drones into their music. John Coltrane was an early and necessary exemplar: the Big Four were profoundly influenced by his transformative work of the early ’60s (Reich once said that Coltrane’s 1961 album “Africa/Brass” “proved that against the drone or against the held tonality anything eventually was possible”). As George E. Lewis has argued, we can and should see Coltrane as a crucial early minimalist.

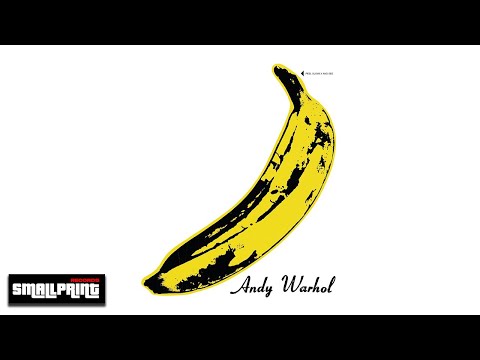

Velvet Underground, “Heroin” (1967)

“It seemed like a very powerful encounter in a sense, each of them moving in a direction which was daring and audacious for the other as well as themselves.” —Tony Conrad on the early Velvet Underground

The cultish aura of the Theatre of Eternal Music, a pioneering minimalist ensemble that gave multi-hour droning performances in New York in the early ’60s, is still hard to penetrate: Due to disputes among its original members, only a tiny fraction of their music can be heard, all on bootleg recordings. But a version of the group’s ritualistic drones also found its way into the proto-punk of the Velvet Underground via violist John Cale, who played in both groups and can be heard sawing away in the feral classic “Heroin.”

Such early intersections between minimalism and rock continued: The Who messed around with Riley-style loops on “Baba O’Riley”; Bowie and Eno paid tribute to Glass and Reich in their Berlin trilogy; and Sufjan Stevens riffed on Reich’s “Music for 18 Musicians” on “Illinois.”

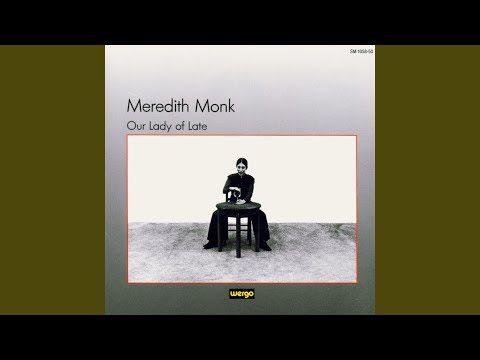

Meredith Monk, “Our Lady of Late” (1973)

“She sat down, concentratedly arranged herself. Dipped her fingers into the wine glass and started to play. Her voice wove in and out of the wine glass note, her voice made crooning wine glass circles for a while. There was something comfortable, basic and soothing in the wine glass sound: constant, single, singular. Above it Monk’s voice began to explore, to break out of the circles to come back to the circles. She was starting to teach us, not with words but with sounds or syllables, a new language or a new world.” —Sally Banes on Meredith Monk’s “Our Lady of Late”

“Process” was the name of the game in early minimalism: all kinds of composers were messing around with tape loops, gradual processes, phasing, “systems music.” In her multidisciplinary spectacles of the ’70s–to which the Village Voice dispatched its music, theater, and dance critics—Meredith Monk took a deeply intuitive approach towards musical process, adorned in “Our Lady of Late” with just a wine glass and her voice.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

Laraaji, “Celestial Vibration” (1978)

“Playing this instrument out of a state of meditation allows my meditational state to be communicated…so if I am in a state of oneness with the Divine Presence, which is always here—it’s just a fact of remembering it.” —Edward Larry Gordon, aka Laraaji

Minimalism emerged as part of a lifestyle that often included yoga, meditation, and psychedelic drugs: the hallucinogenic music inspired its creators and consumers to achieve the altered states of consciousness that were all the rage at the time. In the ’70s, the ambient musician Edward Larry Gordon, who would soon be known as Laraaji and release music on Brian Eno’s label, created astonishing soundscapes on his autoharp, driven by deeply spiritual concerns. (His incredible 1978 album “Celestial Vibration” was recently reissued, with a ton of newly discovered material, on Numero Group.)

Catherine Christer Hennix, “The Electric Harpsichord” (1976)

“The listener’s attention is monopolized; the physical vibration is physically felt; the uniformity of texture produces a sense that time is suspended. This aural texture works, without any themes to recognize, to stimulate hallucination or logically anomalous perceptions.” —Henry Flynt on “The Electric Harpsichord”

1976 was the turning point for minimalism: the year of Reich’s “Music for 18 Musicians” and Glass’s “Einstein on the Beach,” evening-length masterworks with sold-out premieres that launched their creators onto veritable career paths. (Finally, they could cease their plumbing and cab-driving side gigs.) Though still controversial, minimalism was soon celebrated in mainstream magazines, performed in concert halls, and released on major record labels. But 1976 was also the year of a lesser-known magnum opus, one that points to the movement’s continued trajectory in the underground: Swedish musician Catherine Christer Hennix’s densely mathematical but uncannily beautiful “The Electric Harpsichord.”

Ellen Fullman, “The Long String Instrument” (1985)

“I am an outsider to music, and it’s as if now I am seeing the inner workings, the gears, pulleys and bricks that build music and it’s my intention to affect the listener in this same way….My interest in doing this work is in the experience of listening.” —Ellen Fullman on the Long String Instrument

Not all minimalist lineages lead back to the Big Four. Sound artist Ellen Fullman encountered the music and ideas of Alvin Lucier and Pauline Oliveros in the mid-1980s, which helped fuel her drone-based Long String Instrument. In the opening track of her 1985 debut, “Woven Processional,” performed with Arnold Dreyblatt, Fullman’s massive installation wavers between buzzing drones and soaring overtones. (Her most recent work, like “Elemental View” with The Living Earth Show, is more pulse-based, using a vastly expanded instrument of 134 strings.)

Elodie Lauten, “Variations on the Orange Cycle” (1991)

“What I liked about minimalist music is that it induces a kind of a trance, but eventually the trance state induced by the repetition makes you forget the music. I wanted to stay with the flow and not go beyond it, so there had to be more stimuli in the music, variations of rhythm, of accents, of notes.” —Elodie Lauten

In the ‘80s and ‘90s, a new generation of musicians arose who were profoundly influenced by minimalism’s early progenitors, but less concerned with the strictness and abstraction of the music’s early period: the postminimalists. Some were classically credentialed composers, bringing the pulses of Reich and Riley into complex, notated chamber works; others, like Elodie Lauten, were writing songs and playing in bands but transitioned to instrumental experimentation. Lauten’s 1991 “Variations on the Orange Cycle” is emblematic of this time: a large-scale piano work with a teeming, wandering approach she dubbed Universal Mode Improvisation.

Jace Clayton, “The Julius Eastman Memory Depot” (2013)

“The carefully ordered canon is better thought of as a site to traverse rather than a resting place… Spotlights create shadows. How to turn off these bright lights?” —Jace Clayton

Although his music seems to be everywhere these days, Julius Eastman never sought to be part of any canon, as Jace Clayton wrote in a trenchant 2020 essay. Clayton’s 2013 “Julius Eastman Memory Depot,” an early and important moment in the recent revival of the composer’s work, transforms and reinterprets the Eastman’s music with live performers and electronics. Accompanied by theatrical interludes, in which Clayton playfully poses as an Eastman impersonator, the “Memory Depot” provocatively challenges the veneration that has come to define “Eastmania.”

Éliane Radigue, “Naldjorlak” (2005)

“What a strange experience after so much wandering, to return to what was already there, the perfection of acoustic instruments, the rich and subtle interplay of their harmonics, sub-harmonics, partials, just intonation left to itself, elusive like the colors of a rainbow.” —Éliane Radigue on “Naldjorlak”

Our book concludes with the words of the GOAT of minimalism, the doyenne of drones: Éliane Radigue. As the Big Four approach their 90s it is a miracle that they are all still with us—Radigue is 91 and still making mind-bending music. “Naldjorlak,” just released on Saltern, is a years-long collaboration between Radigue and cellist Charles Curtis. Its haunting, questing exploration of the cello’s wolf tone reveals what minimalism has always taught us: how to say so, so much with very, very little. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.