- Justina Jaruševičiūtė: “Silhouettes” (Piano and Coffee Records)

- Camerata Zürich, Igor Karsko: “Leoš Janáček: On an Overgrown Path” (ECM)

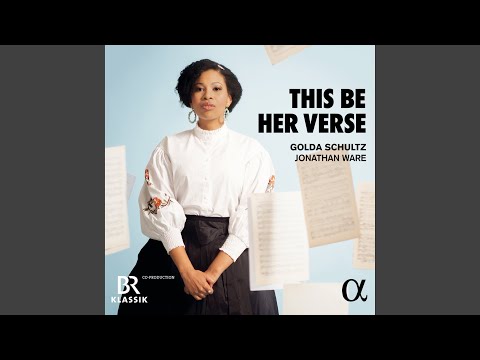

- Golda Schultz, Jonathan Ware: “This Be Her Verse” (Alpha Classics)

Justina Jaruševičiūtė describes the “Wolf Hour” as “that time of night in which people wake up without any particular reason and can’t fall back asleep.” It’s an hour I imagine many of us have grown familiar with over the last two years, though I’m not sure how many of us spent that time as productively as Jaruševičiūtė, who used it to think through the music that forms “Silhouettes.” The album-length work, which came out last March, charts the stretch of time between the hour of the wolf and an eventual, inevitable sunrise. Jaruševičiūtė pays close attention to the stops along the way, as if each one was a station of the cross.

Minutes tick by like hours in Jaruševičiūtė’s music, as we surrender to the slow, syrupy move of crepuscular time. The opening “Wolf Hour” begins unsteadily, almost Mahlerian in its layering of subjective experience over the routines of the natural world. Being awake in the middle of the night and unable to fall back asleep is rarely a neutral state. This carries through into the second movement, “Prayer,” whose supine musical lines recline across chasms of stillness, aching and arching towards a reprieve. Simple motifs slide into complex tangles of repetition and lines passed back and forth among the members of a string quartet (actually two string quartets, who often switch between tracks). The music builds towards that sense of deliverance as the hours pass with gleams of hope along the way—“Reminiscence” offers a few flashes of morning light in upper register bowings that pick up once again in the following “Distant Star.” By the time “Sunrise” tiptoes in at the end, after so much time feeling out every corner of the night, the effect is one of profound illumination.

If all of this sounds a bit like the same methodical simplicity and slender enlightenment of the late Icelandic composer Jóhann Jóhannsson, that’s by design. The Lithuanian-born, Berlin-based Jaruševičiūtė heard the premiere of Jóhannsson’s own restless “12 Conversations with Thilo Heinzmann” in September of 2019. It delivered a flash of inspiration; the sleepless nights that began to follow shortly after that autumn incubated it.

There are echoes of Janáček in the way Jaruševičiūtė coaxes out blooms of lyricism against liminal dissonance, augmented by some of the natural folklore that makes its way into titles like “Wolf Hour.” In fact, I was reminded of “Silhouettes” thanks to Janáček—more specifically, last November’s release of “On an Overgrown Path,” reinterpreted for string orchestra. In their original form for piano, musicologist John Tyrrell described the songs comprising “On an Overgrown Path” as “some of the profoundest, most disturbing music that Janáček had written, their impact quite out of proportion to their modest means and ambition.” The deceptively sweet “Good Night!,” for instance, sounds like it may be one of those Brahmsian lullabies that carries no more turmoil than a Pottery Barn nursery. However, there’s an underlying unease that comes across in hearing it on piano—and it’s one that’s carried full tilt in this string orchestra redux.

“Perhaps you’ll hear parting,” Janáček wrote to musicologist Jan Branberger of “Good Night!,” and this—combined with the way the melody is swallowed up, “Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind”-style, into the bassline—alludes to the shadows contained within the composer’s nostalgia. Igor Karsko and Camerata Zürich are quick to pick up on this unsettling texture, juxtaposing idyllic melodies with thornier counterpoints.

Rooted in Moravian folk songs, though often as similar to them as a poodle is to a wolf, “On an Overgrown Path” is as much connected to verbal language as musical language. Camerata Zürich’s recording also includes a selection of poems inspired by the composer, written and read (in French) by Maïa Brami. These poems, coming in between Books I and II of the cycle, come as a bit of a shock; like waking up with a start in the middle of the night, groping for the clock, and realizing you still have hours to go before daylight. Sink into the language, however, particularly the warm viola of Brami’s voice, and it feels like a worthy rest stop between music, finely tuning the brain into a mode of even deeper listening.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

It’s a threadbare connection between “On an Overgrown Path” and soprano Golda Schultz’s “This Be Her Verse,” but bear with me: Janáček borrowed his title from an old Moravian wedding song, which has been said to begin with the painfully nostalgic line, “The path to my mother’s has become overgrown with clover.” I can’t shake this image from “The Wedding,” one of three songs by Kathleen Tagg and Lila Palmer that form the album’s eponymous song cycle. A sort of post-Moravian, post-post-modern scene from a marriage, Palmer describes a scene without confetti, just sun and cement “baking the just completed act into sticky reality.” This isn’t rose-hued nostalgia; it’s brutalist reality. The bride waits for her groom, impatient, seething. A hand is laid on her arm: “Dearest, you should know…You will always be waiting, waiting for him to catch up.” Like Palmer, Tagg’s musical language is sparse but precise, packing as much variety of emotion into each word as is possible. The immediacy of the emotions has been mined from Janáček into something as easily accessible to 21st-century singers as it is exceptionally beautiful.

“This Be Her Verse” was a venture described as risky and avant-garde, even in 2022: an album of songs written exclusively by female composers. While not surprising, these assessments are patently absurd; it’s a honey of an album, sticky reality and all. Schultz casts a wide net, beginning with Clara Schumann and Emilie Mayer and continuing through Rebecca Clarke and Nadia Boulanger into the Tagg and Palmer works, commissioned specifically for Schultz. It’s a near-unbroken timeline of composers who lived through the last 210 years, many of whom have been neglected solely for want of a Y-chromosome.

Schumann’s “Liebst du um Schönheit” opens the album warmly and tenderly, soft-footed in its emotional revelation: The narrator pleads not to be loved for the sake of beauty, youth, or riches—and she’s happy to suggest alternatives for each of those wiles. It’s a familiar format that is quickly subverted in its final stanza: “If you love for love’s sake, oh, yes,” she cries. “Love me.” Schultz’s voice takes on a breathless quality in the final lines, uncertainty overcast with hope: “Love me forever, and I’ll love you evermore.”

Schultz’s soprano beams, like a roomful of champagne glasses held up for a wedding toast. But “This Be Her Verse” is as much a showcase of her sharp curatorial eye as it is her crystalline tone. Schumann’s “Lorelei” has the urgency of Schubert’s “Erlkönig,” while Mayer’s own setting of the “Erlkönig” text is introspective and internalized, at times sounding more like the tender “Morgengruß” of Schubert’s “Die schöne Müllerin.” It offers a different dramaturgical lens on the familiar story: a successful seduction rather than a failed rescue mission. She complements these works with Rebecca Clarke’s setting of William Blake’s “The Tyger,” which increases the heat of urgency in “Erlkönig” as if cranking up a bunsen burner. There isn’t a perfunctory word or note in the entire song. It’s music for the Wolf Hour. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.