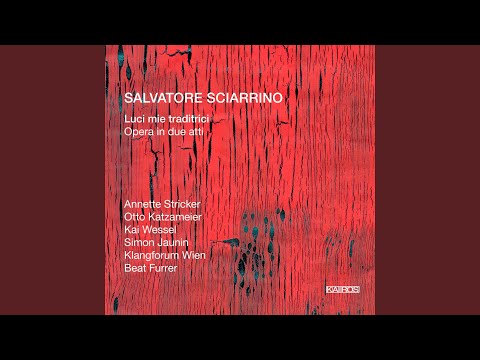

Listening to Salvatore Sciarrino’s “Sei Capricci” for solo violin might best be compared to spending 20 minutes in a butterfly garden. The music rustles, flickers, alights for the briefest moment somewhere, and then flies on. A similar texture lends his classic opera “Luci mie traditrici” (1998) a dreamlike quality. When, in one brief intermezzo of the hour-long drama, he introduces five minutes of regular pulse, it feels like a gigantic tectonic plate has shifted, so sensitive have our ears become. Sciarrino’s new opera, “Ti vedo, ti sento, mi perdo,” was recently premiered at La Scala in Milan. On July 7, it will come to the Staatsoper in Berlin, in a staging by Jürgen Flimm and under the baton of Maxime Pascal. We met over late-afternoon coffees at a conference room there. When Sciarrino received a call on his smartphone, he lamented ever buying one. “I don’t want to give my memory to another instrument,” he said.

VAN: When you first wrote your virtuosic “Sei Capricci,” in 1976, did you think so many violinists would be able to play them? Schoenberg’s Violin Concerto was initially deemed unplayable, but he thought that would change with time.

Salvatore Sciarrino: I’m not that super-optimistic. A composer does what he needs to do. We can’t predict the future. Composing a successful piece can be like shooting a bullseye: we need to be conscious of what we can attain, and then try to go further. I wrote the “Sei Capricci” after several other pieces for string instruments. I was already working on the same kind of articulation—but something about the “Capricci” clicked.

They might seem more traditional or classical, but they’re not. Though there is something about them—they take a model and transform it. That’s important, I think, because there is no language that is totally new. We can’t understand each other if we don’t start with something that’s common between us. And it’s always been that way.

As a child, I was interested in models from history: archeology, art history. Art history was so important for me to connect with music. When I was very young, for example, I felt strongly that Debussy was not an Impressionist, even though everybody said he was. But I thought, “It’s not possible that music comes 30 years after painting.”

Isn’t that possible? It’s pretty common to think that music is “behind” art history.

I don’t think so. Human languages at a given time have common characteristics. Debussy is more Symbolist to me. For example, my professor at university said that “Fête,” the second “Nocturne” for orchestra by Debussy, was his impression of a band in the gardens. Well, now, I say, “No, excuse me. I’m sorry, but it’s not that.” Debussy is very precise with his iconology of sound. You have cymbals and harp: that is a classical procession, in the classical period. So it’s not Impressionist.

We can find points of contact between all forms of art, but musicians don’t like that. The origin is the idea of a pure musical language, from the late 19th century. L’art pour l’art. That’s been horrible for us, because now we don’t want music to have contact with other languages. I want to enjoy music and enjoy everything. No art should be forbidden. Why does it have to be forbidden to connect things? That’s culture: the life of connection. In this sense, I’m like an amateur. I don’t want to be considered a musician; I’d rather be thought of as a music lover.

Is that why you write opera, because it connects with other art forms?

Yes and no. For me, theater is the most social art. We’re together, in a place, but in our heads we go somewhere else. It’s narrative. All the art forms come together, but the main thing is that we are following a story. And that’s fantastic. It’s the miracle of representation.

Of course, musicians and music lovers can follow the form of a piece, which is similar. Though you shouldn’t think that you have to know the music to understand the piece. Musicians often say that: “You’re not a musician, you can’t understand music.” That’s not true.

I agree with you. Why do you think musicians say that?

Because they have a vested interest in it; they’re like a corporation. It’s a very old problem. We want to separate music from reality and the other arts. When I taught, I was teaching how to connect. And I know that I wasn’t very popular with the other teachers because of that.

But connection is the miracle of language. When we hear a piece for the first time, it gets imprinted on us in some way, but the next times are always different—there are infinite variations. It always brings us something new.

We need to be open for that to happen, however. If we’re stuck in a routine it won’t. For example, every coffee shop or restaurant has music. Like…we shouldn’t call it noise, because it’s more like a faked silence. For us, silence isn’t total silence, it’s like those bells we’re hearing now. Our words are in the foreground, and silence, for me, is the further dimension. If we hear a loud car, we can still understand each other, even without hearing every part of every word. We know how to use language, even if the silence is so noisy that it submerges us.

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.

In an interview with the Brooklyn Rail, you said that you find music to be an erotic experience. It can make people uncomfortable, because it touches them in an erotic way.

This is very important for me. I want music to touch me. I like that. That reminds me of a curious experience: I wrote a piece for Riccardo Muti called “Morte di Borromini.” He performed it in La Scala, and at that time there was a row in the back of the hall for wheelchair users. And when he started the piece, I heard a kind of a high cry. Later, I realized that an autistic person had made the sound. Unfortunately, the usher took him out of the concert hall.

Years later, I got in touch with someone who did music therapy for people with autism. At one point, someone asked me to play some of my music to the music therapy session. So I played something, and there was a person who told me, “I like your music because it touches me everywhere.” That was very surprising.

When you call music erotic, is it sexual? Or is about being touched, more simply?

You know, when a sound is forte, you have a physiological reaction. You’re alarmed; you breath more quickly. The sound makes the idea come to you. When the music is pianissimo, it’s far from you. My music is pianissimo, but sometimes there are moments where it’s like the music is coming to you.

It’s not really a question of sexual or not. We want to divide, but it’s better not to divide [laughs]. When it comes to simple things, it’s hard to make precise definitions. We’re talking about music’s deep ability to communicate, not something rational. If we try to be rational about it, we destroy our ability to understand.

When I was working on my opera “Lohengrin,” I wrote the part of Elsa first, which depicts her descent into mental illness. I was visiting some friends in the country, and I played them her part, and their dog reacted as if it had seen another dog somewhere in the distance—barking at the speaker. The timbre was quite different, so it must have been the rhythm that provoked the response. It was an interesting psychological experience.

The music of Gérard Grisey deals with similar questions of perception. Did you know him?

Yes, we were very good friends. We met through our publisher Ricordi, in the ‘80s. At one point I found a summer house for him and his girlfriend, not far from the small town where I live. He stayed in Italy for three years, and had the keys to my house: he wanted to use a piano sometimes, for his most complex chords. He composed “Le temps et l’ecume,” “Le Noir de l’Étoile,” and he started “L’icône paradoxale” while he was there.

Then he and his girlfriend broke up and he met his wife, but he wasn’t able to return to the summer house, because it was connected to his ex in his mind. It had been a very intense relationship. They both had sons but weren’t married, and then Gérard married a second time.

Your operas tend to be around an hour, but I think I could listen to them for five. Could they be longer?

No, I don’t think so. Well, I don’t measure with the time of clocks. I measure in relation to the contrast of different dimensions. In my new opera, “Ti vendo, ti sento, mi perdo,” I don’t distinguish so much between new music and old music, but they are different dimensions. I think relatively: I do cut things, but not in terms of absolute time.

Did you hear? There’s some wind coming through the window. [Whispers] I think it could be coming through the door. You know, it’s very important that we hear the leaves touching each other: that’s the wind, for us. Right now, you have a very high leaf sound, and the general noise of the city.

Do you listen like this often, when you’re at home?

I live in a quiet place. But you can still hear human noises, which is very enjoyable. We soak up everything around us. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.