The grass is always greener on the other side of the Atlantic. Throughout my time in the world of contemporary classical music, this is a message I have heard over and over and over again. Governments in Europe fund their artists much more generously. European audiences are much more invested in their artistic cultures, and are much more open to new work than audiences in the United States are. Whether in reviews, guest lectures, or analyses of an ensemble’s financial difficulties, the message is clear: the landscape for writing and presenting contemporary classical music in the U.S. presents obstacles that the landscape in Europe does not.

So when I sat down with Pierre Audi to talk about his work at, and vision for, the Park Avenue Armory, this was one of my first questions. Audi, who was born in Lebanon and studied in France and England, has been the Artistic Director of the Dutch National Opera since 1988, and of the Armory since 2015, so he is well positioned to talk about making music on both sides of the Atlantic. Are there differences between how eager to hear contemporary music audiences in the U.S. are compared to their European counterparts?

“Well, we’re in New York, which is obviously not the United States,” Audi replied with a chuckle. “We have lots of niche audiences here, and we have a broad audience that doesn’t want to miss anything.” This fear of missing out was a thread that ran through Audi’s comments on the city. “New York claims it doesn’t want to miss anything,” he said. “New Yorkers want to feel connected to other places, to Europe, to the Far East.” And yet for all that he sees New York as being hungry for the same art that’s happening abroad, this hunger has not translated to an oversaturated cultural scene. “International performing arts have a very limited platform in the United States. In New York, they have had a bit of a platform through Lincoln Center, but that’s about it.” In Audi’s view, it’s the work that’s missing, not the appetite for it.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

Indeed, Audi sees this mismatch between audience interest and cultural offerings as a key reason that the Armory brought him on. “They could have chosen somebody very local, who didn’t have a lot of experience with Europe and other parts of the world in order to keep the programming extremely local. I like the combination. I like bringing the voices of artists here together with the voices of artists from Europe, or other continents.”

One such non-local voice is that of the Dutch composer Michel van der Aa, whose chamber opera “Blank Out” had its North American premiere at the Armory in September. “Blank Out” draws from the life and writings of the anti-Apartheid South African poet Ingrid Jonker, and uses film and three-dimensional projection to create a world of memory, trauma, and loss. Audi sees this as “a specialty” of van der Aa’s, and feels that the composer has “gotten better and better at [integrating technology into his operas] over the years.” The Dutch National Opera presented the work’s world premiere in 2016, and Audi was emphatic that even though this is only the second time van der Aa has used three-dimensional interactive projections, “it’s already much more advanced than his first one. It’s so nice to see someone set forth with something very new.”

One might expect Audi to make an offering of performances that brims over with world premieres, but his understanding of novelty is more nuanced than that. “There’s a lot of ‘new’ that still needs to be seen. Sometimes one is obsessed with the world premiere, because you get that world premiere attention, but for me what’s important is making sure the work gets shown as widely as possible.” He offered this as a point of difference from his predecessor, Alex Poots. Audi’s Armory continues to commission new works, but Audi also wants the Armory to be a platform that offers artists a chance “to revisit their work so that it finds a natural, organic home.” In other words, just as Audi is trying to balance the local with the international, he is also trying to balance the “never heard anywhere” with the “never heard here.”

This sense of balancing competing interests extends to Audi’s understanding of the role of the Park Avenue Armory within the broader New York arts ecosystem. “I’m not trying to double-up on BAM or other institutions that are doing their own thing.” Key to this work of avoiding cultural duplication is having a clear artistic mission. Yet this mission isn’t a tidy list of policies written down on a piece of paper or webpage. “The sum total of what the Armory is is the sum total of what the Artistic Directors have done, building up slowly to a kind of philosophy, with different emphases every time.”

Audi, then, would not agree with the young Pierre Boulez, who wanted to blow up Europe’s old opera houses. “You add, you don’t erase,” Audi insisted. “You don’t erase what has happened, you add to it.” He described a process not unlike the formation of sedimentary rock on the bed of a river: “You add another layer with another accent, another color. But I want to believe that each layer is honoring the past layers, highlighting them. Not cancelling them, but developing them, making them grow.” After a moment’s pause, he suggested that this stance might limit some of his career prospects. “If I don’t admire what’s happened before [in a given institution], I wouldn’t be interested in running it.” This isn’t to say that there’s no room for an artistic director to bring an institution to a different place than their predecessor, as Audi has unarguably done with the Dutch National Opera, but unless you’re starting from scratch, the seeds of that change have to be there already. “I’ve been lucky in that none of the institutions I’ve taken over have been stuffy, but I like to build things on fertile ground, so they can grow and blossom and develop. I don’t like cutting trees, or throwing plants away and replacing them with others.”

If New Yorkers’ desire to see everything and miss nothing is the fertile cultural ground in which the Armory develops, does that mean that a place like the Armory couldn’t exist elsewhere in this country? Despite his earlier comments distancing New York from the rest of this country, Audi’s answer was a firm no. “If somebody rich enough wanted an Armory to exist somewhere in the United States and impose it, it’ll work.” He sounded almost surprised to reach this conclusion. Curiously, he went on to say that if the impetus for such a project came from the government, it “wouldn’t have a chance in hell” of working, “but if something is based on the enthusiasm of private individuals, I don’t exclude that from being possible.” The conversation moved on before I could press for his thoughts on why this country might be more hostile to government sponsorship of the arts than private sponsorship, but he did caution that whoever was doing the sponsorship would need very deep pockets. “That’s one thing I have found here: everything in America is very expensive.”

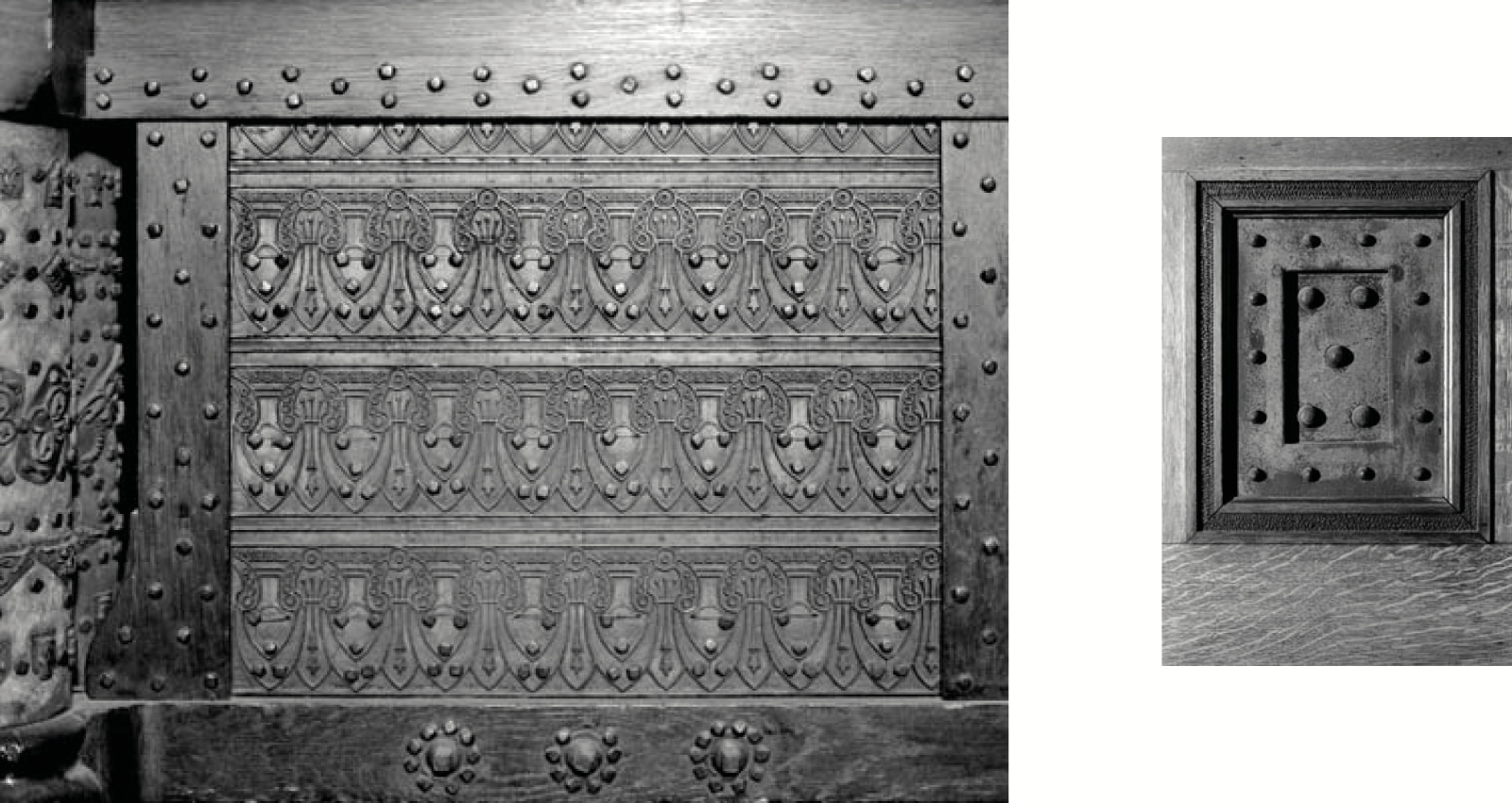

Having an old building to save would help too, he suggested. “There is something perennial happening next to the total opposite: the ephemeral aspect of the arts. After the performance, there’s nothing left!” The juxtaposition between the grand, old, and stately and the new, flashy, and fleeting seems to be woven deeply under the surface of Audi’s vision for the Armory, and feels like a fitting match for the building’s transformation from military compound to cultural institution. There was no music happening while I was there, so I left the building in silence, a venerable space waiting to be filled with novel sound. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.