The death of a classical musician is a moment of loss, but it’s also a moment of rediscovery. Especially when the musician in question is someone like Slovak soprano Edita Gruberová, whose death in Zürich this past Monday, October 18, was an opportunity for fans and houses alike to pay tribute to some of her greatest performances. In one of the earliest examples of her work, a 1968 recital from Czechoslovak television, you can hear much of what would define the next 51 years of her career: an almost effortless upper range, a fluid yet pinpoint-precise coloratura, and an irrepressible joy in the music itself.

Gruberová had her moments of stepping outside the bel canto genre (including one of the hottest Saint-Sulpice scenes in Massenet’s “Manon”), but she made a career out of the genre’s classics and rarities, never abandoning them as a stepping stone to more dramatic or lyric repertoire. The open style of bel canto vocals—emotionally-guided melodies over simple, elegant rhythms—leaves little room for the singer to hide. Not that Gruberová needed a reason to hide. In this repertoire, she was completely herself and utterly at home.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: “Crudele! Ah non, mio bene… Non mi dir” from “Don Giovanni” (1787)

It’s hard to talk about Gruberová’s career as a bel canto soprano without first mentioning the silky delight of hearing her Mozart heroines. Her career-making audition at the Wiener Staatsoper was cinched by the high Fs in her Queen of the Night aria (a staccato line she kept in remarkable form for nearly 20 years), and she was no slouch in “Die Entführung aus dem Serail” or “Così fan tutte.” But in terms of personal favorites, I will always gravitate towards her Donna Anna, which in this particular performance from 1990 shades her coloratura with a silvered edge of grief.

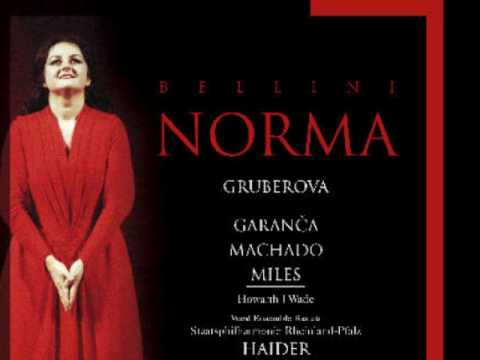

Bellini: “Mira, o Norma” from “Norma” (1831)

There is no shortage of Gruberová performances of “Casta diva.” But one of her assets as a singer was her ensemble work. Many singers spoke of the fear that came with performing alongside Gruberová, but she rarely left colleagues out in the cold. It was especially illuminating to hear her in mezzo duets, as it brought out some of the earthier tones of her stratospheric soprano. This is especially true in her 2005 recording of “Norma,” which features a young Elīna Garanča as Adalgisa.

Bellini: “Eccomi… O quante volte” from “I Capuleti e i Montecchi” (1830)

At 21, Gruberová was traveling between her small town outside of Bratislava and Vienna, aware of the tightening borders between eastern and western Europe. While she refused to join the Communist Party and had watched her father suffer for the same choice, she had plans to continue her vocal studies in Russia. That year, however, saw the violent repression of the Prague Spring.

Married and pregnant, Gruberová, her mother, and her first husband (composer and musicologist Štefan Klimo) abandoned Czechoslovakia for Austria in 1968. By the end of the 1970s, her career had taken off via the Wiener Staatsoper. The same couldn’t be said for Klimo. This in part led to the couple’s divorce in 1983, followed shortly thereafter by Klimo’s suicide. The following year, Gruberová’s mother—who was essential in helping to raise her two children while she was performing—also died.

It was the same year in which she sang Bellini’s “I Capuleti e i Montecchi” at the Wiener Staatsoper. The catharsis is apparent in Giuletta’s plaintive aria, sung when she is alone and desperate for Romeo to deliver her from her torment. Judging by the 60 seconds of applause that followed, it was felt in the house as well.

Donizetti: “Il dolce suono… Spargi d’amaro pianto” from “Lucia di Lammermoor” (1835)

Don’t just listen to this performance of the mad scene from “Lucia di Lammermoor.” Watch it. While the quality is what you might expect from a video transfer that’s nearly 40 years old, Gruberová’s physicality as Lucia adds depth and dimension to a pitch-perfect coloratura showstopper (continuing ecstatically with the act’s finale). With wig and nightgown that both seem like extensions of her own skin tone, Gruberová looks especially ghostly, aided by a gaze that vacillates between hollow-eyed detachment and an almost religious ardor.

This is also prime territory for Gruberová to let her coloratura roam freely. While not a slow singer by nature, the soprano never hid sloppy technique behind rapid-fire arpeggios. She luxuriates in the chase up to a high note, taking sensual pleasure in each step, rather than being laser-focused on the destination (witness a diaphanous, ethereal cascade up to a whisper of a high-B roughly four minutes in). To borrow from Anne Carson’s Eros the Bittersweet, her vocal lines serve as “suspended moments of living hope.” Despite a weathered top and a bit more effort apparent, the suspension was still there when she sang “Lucia” at 72.

Bellini: “Vien, diletto, e in ciel al luna!” from “I Puritani” (1835)

Perhaps it’s no surprise that mad scenes, particularly those in the bel canto tradition, are laden with Eros: They are traditionally those moments in opera where a character becomes most aware of herself, of her desire, and of the separation between the two. Her madness is a moment of pushing through that border, towards as full an experience of ecstasy as possible, before usually crashing back down to earth in a flash of Thanatos.

The heroine of Bellini’s “I Puritani” avoids a tragic end despite two mad scenes. In the wrong hands, it can seem like psychological waffling: Did they have Klonopin in 17th-century England? But in this 2001 performance, it makes sense. Elvira is not a woman slipping in and out of madness like a commuter switching trains; she’s a woman learning to bear the weight of her own desire.

Jacques Offenbach: “Les oiseaux dans la charmille” from “Les contes d’Hoffmann” (1881)

Humor in opera is not easily pulled off. More often than not, it falls flat in the painfully awkward chasm of “Trying Too Hard.” Gruberová, however, was genuinely funny. Like Madeline Kahn, she could balance deadpan with slapstick, which forms a potent combination for this 1993 performance of Olympia’s aria. Before the first note, she inhabits the physicality of a mechanical doll destined to short-circuit, her arms never quite still, her eyes constantly blinking, buffering. Perched on her head is a giant yellow bow that grows more ridiculous the longer you watch.

Carl Millöcker: “Ach, wir armen Primadonnen” from “Der arme Jonathan” (1890)

Even better was when Gruberová trained her comic timing on the act of lampooning her own world. You can see some of that glittering social satire in Adèle’s aria from “Die Fledermaus.” It’s also there in her recording of Mozart’s “Der Schauspieldirektor.” Just as fizzily mordant is this B-side operetta aria bemoaning the life of poor prima donnas, performed here on the Austrian television show “Seinerzeit.” It may have been tongue-in-cheek, but Gruberová—who spoke candidly in later years of the toll that being a traveling singer had on her family and her psyche—imbues it with a silo of truth, expressed in the duomo-arch of an eyebrow.

Bellini: “Sono all’ara” from “La Straniera” (1829)

After moving to Switzerland, the Opernhaus Zürich became Gruberová’s hometown stage. In one of those stories that epitomizes industry legend, she broke with the company in 2001 after her daughter, Barbara, was injured during a performance. Barbara had to give up her career as a dancer following the incident, but the company’s then-director Alexander Pereira denied any responsibility for the matter. In response, Gruberová refused to perform with the company while Pereira was at the helm. It was a move that was pure big dick energy.

Pereira left the company in 2012. True to her word, Gruberová returned to the stage, first as a replacement for a recital cancelled by Jonas Kaufmann, and then in a new production of Bellini’s “La Straniera.” It was a convoluted plot, even by bel canto standards, but worth it for her final cabaletta.

Donizetti: “Quel sangue versato al cielo” from “Roberto Devereux” (1838)

Was there ever a better role as a retirement vehicle? Gruberová sang all three of Donizetti’s Tudor Queens (including a white-knuckle “Anna Bolena”), but it was as Elizabeth I that she retired from opera in 2019. This is an earlier performance of the same production for the Bayerische Staatsoper, and it is an apotheosis of the soprano’s 51 years onstage: the plaintive despair of her 1984 Giulietta, the wild-eyed collision of Eros and Thanatos in her 1982 Lucia and 2001 Elvira, the self-awareness of her poor prima donna, and the steely anguish of her 1990 Donna Anna. Her collapse at the end, wild-haired after removing her Margaret Thatcher-ish wig, is like watching Olympia finally come apart. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine, and we’re able to do so in part thanks to our subscribers. For less than $0.11 a day, you can join our community of supporters, access over 500 articles in our archives, and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

(PS: Not ready to commit to a full year? You can test-drive VAN for a month for the price of a coffee.)