In April, tenor Ian Bostridge released his latest book, a brief meditation on the intricacies of vocal interpretation in music by Monteverdi, Ravel, and Britten titled Song and Self: A Singer’s Reflections on on Music and Performance. In May, he gave a recital at the Boulez Saal in Berlin, with pianist Julius Drake, of works by Robert and Clara Schumann, Schubert, Mahler, and Hans Werner Henze. Bostridge, who wrote his dissertation on witchcraft before beginning his singing career, combines his erudite explorations of the repertoire with an unstudied, spontaneous approach in performance—a combination that often leads to staggering results. I met him the afternoon before his Berlin recital in the lobby of his hotel. We talked about whether lied concerts should have trigger warnings, programming diversity, the elusive definition of quality, and what he learned from crooner Tony Bennett.

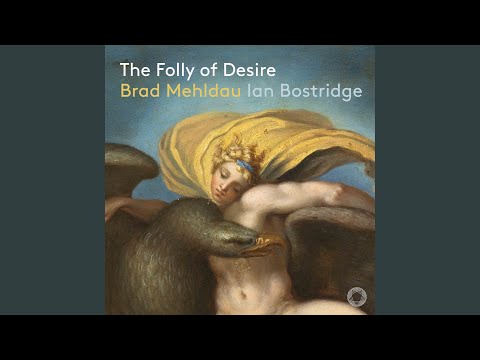

VAN: A recent Bachtrack review by Chanda VanderHart of your performance “The Folly of Desire,” with pianist and composer Brad Mehldau, said that one piece, based on a poem by e.e. cummings, “requires a trigger warning.” Did you see that review, and what was your reaction to VanderHart’s argument?

Ian Bostridge: I mean, we’ve done this piece a lot, and I felt there could have been more engagement with what the piece is about. I don’t think anybody had engaged much with what Brad had written. But I thought there was a deep conceptual error [in the Bachtrack review] with the approach to what art does. It also quoted, out of context, small snippets of what Brad wrote [in his program note], which actually was very considered and interesting.

The review was talking about depictions of sexual assault and rape…

The first poem, “On the Seduction of Angels,” is by Bertolt Brecht. The very first time we did it, at [the Bavarian hotel and concert venue] Schloss Elmau, two ladies came up to me and said, “We’re so shocked, we found the Brecht so misogynistic.” It’s a complete misunderstanding about the poem, because the poem is homoerotic. It’s not about women at all. That’s to start with. Then they said they couldn’t believe that an English gentleman like me would speak such rude words, like “fuck,” ficken. Brecht wrote the poem in response to Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice, as an exposé of what he felt was Thomas Mann’s hypocrisy in presenting what was essentially a piece of homoerotica as if it was spiritual. So it’s about fucking an angel. That’s Brecht. What’s interesting is the Brecht estate will not allow the poem to be translated into any other language than German. So if you do it in America, nobody understands what it means. I assume because [the estate] thinks it’s offensive, which is so un-Brechtian. [Laughs.]

The e.e. cummings poem is about jocks and their awful attitude towards women. It’s not saying, This is a good idea. It’s the folly of desire, representing different forms of desire. And “Leda and the Swan” is an amazing setting about a rape. It’s not saying rape is a good idea.

I think trigger warnings are a particular feature in American universities. Maybe there has to be a bit of pushback, because otherwise it’s going to take root. Speaking as a historian, it must be coming from somewhere, socially. I suppose it’s coming from a feeling that there are a lot of very much more important things to worry about which are almost too scary to worry about.

I think the pieces are masterpieces, but like [other] great works of art, they are shocking and troubling and upsetting. And they should be.

Another criticism in the review was that all the composers and poets were white men. Is that something you think about when programming: the identities of the artists whose work you sing?

[A long pause.] I don’t know. I suppose I don’t think about that. And I feel if I was putting forward a program that was ideologically driven in some way, I would feel that I was being a bit of a fake. I mean, I do Schubert and Schumann. Those are the things I do. If I happen to sing songs that are by people from ethnic minorities or by women—I wouldn’t construct something [around those identities], I’d feel I was being a fake. And I think it’s great that it’s happening, and that lots of people are doing it, but I don’t think it’s particularly my thing.

In your new book Song and Self: A Singer’s Reflection on Music and Performance, you discuss the one time you performed Ravel’s “Chansons madécasses” (“Songs of Madagascar”): “Should I be performing these songs? Do I have the right to do so?”

Yeah, I don’t know if I’ll ever sing that again. I mean, I can’t take on the identity. I think there’s probably lots of tokenism going on, as well, from certain quarters. I don’t know. It’s difficult.

In your recital at the Boulez Saal here in Berlin, with pianist Julius Drake, you are singing two songs by Clara Schumann…

Yeah. We’re doing 10 of 12 songs from the Lieder op. 12, which is a set of songs Clara and Robert wrote together when they were married. Two of them are duets, so we’re only doing 10 of them. The penultimate one, “Warum willst du and’re fragen,”—it’s the most amazing song. I’d forgotten and I’d sort of assumed it was by Robert. And then I discovered it’s by Clara. I think it’s the best song in the set.

What speaks to you about it?

It’s very difficult to define it. It has an incredible simplicity and authenticity of feeling. It’s very moving. I mean, I’m quite a sentimental person. It’s got wonderfully subtle harmonic little twists. It’s fabulous.

But we have to face the fact that in the 19th century all these groups of people were to some degree excluded. So there isn’t going to be the quantity. If you believe in excellence… if you don’t believe in excellence, if you believe it’s all socially constructed, then fine. But if you believe that somewhere, there is something that makes Beethoven a genius composer, then you have to recognize that Beethoven in the 1820s was not going to be a woman, because women were not given those possibilities.

What we should be thinking about is the possibilities we give to people now. In the same way that we can get agitated about slavery in the 18th century—and it’s agitating—but the thing that really matters, and is shocking, is that there is still so much slavery or quasi-slavery going on now. We’ve all got these things [he holds up my iPhone]. What are we going to do about the fact that you can’t make an ethical smartphone? We’re all implicated.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

It sounds like you are a believer in excellence as more than something that’s socially constructed.

As a historian, I’m always looking at what lies behind things, and contextualizing. I was interested in “Chansons madécasses” because I heard it and thought it was mysterious. I wanted to get to the bottom of what was being done with it ideologically. But at the same time, the reason I did that is because I think it’s really good. And why something is good is a bit mysterious.

I feel like defining what’s good gets to the heart of the matter.

In the end, there’s something human and personal about it. Musicologists can’t explain it either. You can go on until the cows come home about the harmonic progressions, but sometimes it’s the sheer simplicity and the context that hits you. It’s often drama, how things stand next to each other. But obviously, there are also musical things that are extraordinary, and Western classical music is a great invention. What’s remarkable about the Western classical tradition is the discovery of notation, and the way that has changed the relationship between music and performer, and the way it hooked up to capitalism and changed our view of time.

When you say you’re a sentimental person, what do you mean?

I cry at music, and it moves me. I’d find “Warum willst du and’re fragen” moving if I didn’t know anything about it, but the fact that I know that Clara and Robert Schumann had this terrible time, and they really loved each other, but everything went really wrong… The fact that they had to fight her father and the fact that Robert went mad. If you’ve read the account of her last meeting with him in the asylum…

What’s music if not human? I mean, there’s a whole tradition of music thinking that it’s not human, which goes back to medieval ideas of the music of the spheres and that somehow music can be abstract. But for me, music is expressive.

Can you remember the last time you cried at music?

It was probably listening to some Schubert, but I can’t remember what. [Laughs.] I think the String Quintet.

You can’t really sing if you’re crying, so how do you wall off that emotion from your performing self?

You just have to resist. It’s very difficult. I did an amazing production of Britten’s “Curlew River” with director Netia Jones. And I had to be moved, because the woman is moved. But on the other hand, I had to keep it slightly at bay, but when the boy appears and sings… Again, it’s a simplicity that’s unbelievably upsetting.

How do you retain control of the vocal apparatus in that situation?

Swallow. [Laughs.]

Have you been following the Arts Council England cuts?

Yeah. Really terrible. We have this thing in England called the National Health Service, which is in many ways unwieldy, but it’s a wonderful idea. And the idea of the National Health Service is also sort of the idea of the Arts Council. It goes back to what we said about excellence: There is excellent art in the world, and it should be available to everybody, regardless of how much money they have. The Arts Council gets it from both directions: it gets it from the right, because the right wants to cut money and is populist and thinks everything should be according to the market. And the left feels that there isn’t really excellence, there just should be diversity.

How does culture function in an age of globalization? The UK, particularly London, is a really multicultural place, which is amazing. But you can only really get a handle as a person on one or two cultures at a time. The culture you embed yourself in is the one that’s going to move you. I’m embedded in Western classical music. I’m interested when I hear Japanese music, but it would require an enormous amount of incredible effort that I’m already expending on Western classical music to discover all these other things.

There are good musics and bad musics. There are musics that have developed a degree of extra capacities to be expressive, and there are ones that haven’t. I don’t know what they are. We probably shouldn’t think everything’s equal, but I don’t think that should be a colonialist attitude.

The way I always think about it is, there’s excellent music within every imaginable genre, and there’s bad music within every imaginable genre.

Yeah, that’s what people say.

Do you not think that’s true?

I don’t know. I really veer about pop music. I like Bob Dylan, his lyrics and his performance style. I don’t know if I find it musically interesting. But then it’s partly also because I’m musically uneducated.

I’m always worried about what is going on in pop music. I’m probably just a terrible snob. But I have this teenage rebellion against [pop music]. Maybe that’s what it is: a pushback against the dominance of pop music, and the pretense that pop music is the music of rebellion, when it’s actually the heavily marketed music of late capitalism.

Maybe that’s what I look for: music that has some sort of authenticity. But it’s very difficult to say what that is.

The other thing about classical music is, it’s inner directed. I mean, it’s involved in this whole world of money and power. But when you actually make a CD or do a rehearsal, you never have your eye on the plot. You will fuss about something absolutely tiny, just to get it right. And what’s right is not clear. We pretend it’s obeying the dictates of the composer, but it’s not really. And there’s something very liberating about how there isn’t an accountant. And there shouldn’t be. This is the problem with the Arts Council. There shouldn’t be an accountant saying, Oh, well, actually, you’ve now spent half an hour on this particular bar. It’s not worth it.

For me, it’s also a class issue. I think everybody assumes that I’m some terribly posh person. Neither of my parents went to university. My father left school at 14, my mother at 16. They both went to grammar schools, which were these amazing free schools with quite high academic standards, but they left. My father didn’t go to the theater or to classical music concerts. There is this sense of it being something that’s been won. And I don’t want people to be casual about it and lose it.

That makes sense to me as someone whose parents don’t have a classical music background: That feeling that you have to earn it.

When I was younger, I would discuss with Julius Drake. He was incredibly fluid on the radio and would always talk about a piece being a work of genius. And I’d say, “But what do you mean?” And I’d get really Oxbridge-y irritated about it. But now I’m actually more with him, because this is an area of incredible human achievement. We shouldn’t throw the baby out with the bathwater.

Do you feel that there are differences to your approach having not grown up in classical music, as many classic successful classical musicians do?

Having said all that stuff about popular music, maybe I do bring all the music my father listened to when I was a child—Frank Sinatra, Tony Bennett, Andy Williams—[to my idea of] how you should sing. I never really liked the sound of opera singing.

And then there’s also the feeling that you should be free with it. Being true to the score, or true to the composer, is a useful hermeneutic interpretive tool and a useful discipline, but in the end: They’re dead. The responsibility is to make something living for the audience, and someone else can come and do something different. It’s not like you’re throwing acid over the “Mona Lisa.”

Reading Song and Self and also your 2014 book Schubert’s Winter Journey: Anatomy of an Obsession, I got the sense that writing was a way for you to put interpretive ideas that are fleeting in performance, and that might not be perceived by every audience member, into more permanent form. Do you think that’s true?

Yes, some of it is more generalized and fits, and some of it is fleeting and is just gone. And it is a very weird experience when you do things like “Winterreise,” which you’ve done so many times: as you’re performing it, a new ideas related to the piece might come into your head, new tiny rubatos or little things that you might do between the voice and the piano. You make these discoveries, and then you completely forget them. It’s weird, because they are the stuff of interpretation. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.