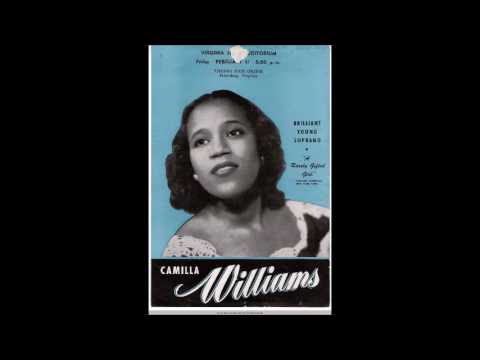

For a long time, the world of opera was blindingly white—until soprano Camilla Williams became the first Black singer to perform on a major American opera stage. In 1946, she made her debut at the New York City Opera as Madame Butterfly, opening a door that had been closed to people of color up until that time. She was active in the civil rights movement and, in 1964, she performed in honor of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. at the Nobel Peace Prize awards ceremony in Oslo.

Williams was also a teacher, and among her most successful students is Janet Williams, a longtime member of the ensemble at the Staatsoper Unter den Linden in Berlin who has also performed across Europe and at the Metropolitan Opera, the San Francisco Opera, and the Washington Opera. Today, Janet Williams lives in Berlin and teaches a private vocal studio. In a Zoom call, she told me about her years studying with the legendary Camilla Williams.

VAN: You studied with Camilla Williams when she was teaching at Indiana University in Bloomington. What was your first impression of her?

Janet Williams: Before I met her, I had read about her in a book. I knew about her career and how she had been a pioneer and a trailblazer. The first time I met her in person was when I auditioned for her in Indiana. I will never forget the all-yellow outfit and the humongous straw hat she was wearing that day. She wanted to hear some Mozart from me, so I sang Donna Anna for her. After I finished she looked me up and down and said, “You have talent, but you sing back. You need to bring your voice more forward.” I had no idea what that meant. Until then, no one had ever criticized me before. People had always just told me how talented I was. But something in me knew that this woman knew what she was talking about, and that she would be able to help me.

Did you ever get to watch her perform on stage?

Yes. All of the teachers had to give faculty recitals. In those she would sing German Lieder, because she believed that these small vignettes really showed all the colors of a performer’s artistry.

What did you admire most about her artistry?

I loved the purity of her singing. There was a genuineness about her delivery that was never affected. When I met her she was already in her 60s, but her voice still sounded so youthful. She also had a really unbelievable top. Her high B-flats and Cs were just incredible.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

How would you describe her teaching style?

I would call it old school. She had a way of describing how she sang. And that’s what she taught. Everyone got the same exercises and technique, there was only one way. So for those who didn’t get it, she didn’t have many alternative tools in store. Luckily, I got it. I could do what she wanted.

Camillia sang the big leads in Verdi and Puccini operas, while you made a name for yourself with your fast coloratura. How did the technique that she taught help you with that?

Well, coloratura always came naturally to me. Still, Camilla never believed I was a coloratura. She felt that my voice was very similar to hers. And it was! Her voice was actually pretty light for some of the roles that she took on. At that time, there was a precedent for Black singers to always sing Aida. She wasn’t a typical Aida, but she sang with her own voice. So when I was with her she taught me all those big roles: Mimi, Violetta and so on. Other people, however, heard my flexibility and saw my size and categorized me as a lyric coloratura. And when I then took those roles to the lessons with her, she would be like, ”Why are you singing that? And when are you singing Butterfly?” But in the end she realized that I was getting a lot of good work in the coloratura Fach, so she came around.

Some people say that they hear their teacher’s corrections in their head while practicing, even years after finishing their studies. Does that sometimes happen to you?

That happens to me mainly when I’m teaching. Camilla is with me all the time when I’m teaching. She had this way of saying, “Drop your jaw and lift!” And I would ask, ”Lift what?” And then she would say, “The breath, the breath!” Now I understand what she meant by that: Finding a lift in your inner space and directing your resonance up. You want the feeling that the voice goes up and over. So now, whenever I hear a singer not directing their sound up, I immediately think, ”Drop your jaw and lift!”

What is the best advice she ever gave you?

Camilla was a big proponent of positive thinking. She really believed that what is meant for you will come to you. She would say, “Oh honey, if you don’t get what you want, God has something better in store for you.” Her faith was a big part of her teaching. There’s a little mantra that she gave to all of her students. It goes like this: “God go before me, behind me, on each side of me. God surround me and God sing through me.” I took these words with me all over the world. It was my prayer before I went on stage. It really focused me and reminded me that it’s not just me out there, but the Creator working through me [with] the gift that he gave me.

Did she ever come to hear you sing in Berlin?

She heard my Pamina at the Staatsoper and she was so proud. She told me after the performance, “You are now a Mozart singer, my dear.” She always used to say, “If you can sing Mozart, you can sing anything.” So that was a beautiful compliment.

Did you work on Pamina with her?

Yes, of course. She taught me how to float and how to sing piano. I used to worry about my middle range. But Camilla would just say, “Sopranos get paid for their high notes, Janet. Don’t worry about your middle, it’s gonna come when you get older.”

When Camilla was starting out as a young singer, racial segregation still made it very difficult for people of color to follow their dreams. Did she ever talk to you about how that may have affected her career?

She was very open about the racism she had to go through. She would perform on stage in these beautiful venues and afterwards had to go through the kitchen when she went back to her hotel, because she wasn’t allowed to enter through the front door. During train rides she had to sit in the segregated section. And then the colorism on stage: For roles like Mimi or Nedda she had to whiten her face and could not use her own complexion. There were singers who refused to sing with her on stage because she was Black. Luckily, the conductor of the New York City Opera, Laszlo Halasz, would always be on her side. He would simply say, “If you have a problem, you need to go. Because Camilla Williams is staying.”

Besides Mimi, Nedda, Aida, and Butterfly she also sang Bess in “Porgy and Bess,” right?

Only on a recording. She never sang Bess on stage and she was very much against me singing in a staged version of “Porgy and Bess,” because she felt that the story was degrading to Black people. I said, “Well, but that is part of the Black experience!” She replied, “There are other things to the Black experience and nobody wants to write an opera about that.” But mainly her reasoning had to do with the longevity of my career. She was concerned that if I sang in “Porgy and Bess,” people were never going to see me as anything else.

When I later got my first offer at the Metropolitan Opera it was for Clara in “Porgy and Bess.” When I told Camilla about it she didn’t like it at all. She said, “I dare you to do it!” It so happened that I had another offer from the San Francisco Opera for Nanetta in “Falstaff,” so I took that instead. Later, my agent told me that when he told Leonore Rosenberg, artistic administrator at the Met, that I’d be doing Nanetta in San Francisco rather than Clara in New York, she said to him, “She’s a smart cookie, isn’t she?” So Camilla was right. Thank God things are changing now, but when I was singing, many of my friends who did “Porgy and Bess” were never offered anything else.

What other advice did she give you on how to navigate being a Black singer in a predominantly white industry?

She told me to be myself, but to never forget that I am Black. I guess what she meant was: If you want to make it in this industry, you will be held to a higher standard than your white colleagues. So you always have to bring your best game. To me, that was huge pressure. But again she was right. I would even venture to say that it hasn’t changed much today. The expectation for Black singers still is that they have to really stand out in an exceptional way.

So avoiding “Porgy and Bess” was a good idea. Have there been other instances where Camilla’s intervention saved you from what could have been an unwise career move?

When I first came to Europe I got an offer to sing Frau Fluth in Linz. I was so excited and called her immediately. But she just asked, “Where is Linz?” I said, “It’s in Austria.” She said, “Salzburg is in Austria. Vienna is in Austria. I know those houses, but I’ve never heard of Linz. Do you want to leave your voice in Linz? Is that what you want?” I was so angry, because she just burst my bubble. But she said, “Listen, Janet, you are not ready. If you were ready, Goetz Friedrich would have hired you for the Deutsche Oper in Berlin. Is that what you want? Or do you want to sing and leave your voice in Linz after two seasons? You need to finish studying before you audition.” So I went back to study with her for one more year. And after that I was really ready. Camilla taught me to be aware of what I wanted and not settle for anything else.

Is that something you incorporate into your own teaching?

I do. But I am not so insistent on putting my own will onto the students. I started out a bit like that but now I listen more to what they have to say and let them find their own way. I also don’t get as involved in their personal lives as Camilla did. I mean, she was like, “I want to meet your boyfriend!” And then she’d say, “I don’t like him, don’t bring him into my studio anymore!” She was very much of a mother figure to her students.

What advice do you give to young Black singers working today?

I let them know that they are held to a different standard and that they need to be willing to put in the work to achieve it. We also talk a lot about appearance and presentation. The way that they carry themselves is very important. They should stay true to themselves, but they still have to be able to fit into different types of situations. Camilla would always talk to me about how I dressed. “Take off those big earrings!” and “Where did you get that coat? It’s so loud!” And when I sang my first recital, I had made myself a beautiful sleeveless gown, and she said, “Janet, the recital is in the afternoon! It is before five! You’re not going bare-shouldered!” And she wrapped one of her scarves around me.

Today’s times are different. For example, in my opinion people should not be wearing nose rings on their auditions, but I understand that this is part of their individuality and that they want to express it. Unfortunately for Black people, we don’t have that luxury yet I think. Especially here in Europe with not so many Black opera singers running around.

If you could ask Camilla one more question, what would it be?

I know she had a lot of difficult students. Still, she came in every day with so much enthusiasm and motivation to help them get better. I guess I would ask her where she got that from. I miss her a lot. I am just so grateful that she came into my life. She certainly touched my life in a way that changed me and helped me grow. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.