It starts with the name. He gets irritated when you ask about it. Americans can’t pronounce the “ij” in “Bijlsma,” but the U.S. market is important, so marketing had the last word. He settles for “Bylsma.”

He’s Dutch. In 1959, he won the International Pablo Casals Cello Competition, the Nobel Prize for cellists. When he became principle cello of the Royal Concertgebouw orchestra, he was the youngest person to ever hold the post. And so Bijlsma was ripe for an international career as a soloist, but he didn’t want it. He quit the orchestra after six years, in 1968, and played only chamber music for the next 40 years, until an illness eventually took the instrument from his hands in 2005. The ensemble was called L’Archibudelli—but it wasn’t his. Its core was comprised of his third wife, the violinist Vera Beths, and his close friend Jürgen Kussmaul, on the viola. They were three co-conspirators, none of whom wanted to monopolize the group. Since they had no desire to spend their existence playing little more than Mozart’s Divertimento in E-flat Major, or Beethoven and Schubert’s contributions to the string trio repertoire, they would invite other soloists to join them, and from Vivaldi’s Sonatas to Shostakovich’s Octet Op. 11, the music was enough to keep them engaged.

Why did he leave the Concertgebouw Orchestra so early, and what did he have against a prominent career through the world’s concert halls? “I don’t like to have conductors,” he tells me. “There are a bunch of shitty conductors who look exactly like master conductors, they all behave in the same way….The baton is the unhappiest instrument there is.” He laughs a lot while talking, thoughts jumping from place to place, and his choice of words is casual. Like a lot of Dutch speakers, his German is a little askew, but always colorful and inventive.

As a 25-year-old solo cellist, Bijlsma enjoyed playing thick Brahms Symphonies in the Concertgebouw Orchestra, with 12 cellos and eight contrabasses. “It’s not bad for you,” he says. But one day during the late 1960s, an unknown young man called him and asked if he’d be interested in playing in a trio with another unknown young man—flute, harpsichord, cello. He was interested. The unknown young man who called was the keyboardist Gustav Leonhard. Bijlsma decided to aim for communication, rather than proclamation in music; it would become the guiding philosophy for the rest of his life. “The more chamber music you play, the less you talk,” he says. “There are colleagues who talk and colleagues who say nothing. I don’t know who has more influence: a contrabassist who plays it right or an oboist who’s always talking and might cause difficulties.”

His aversion to the brotherhood of conductors isn’t just about authority or his love for chamber music, it’s about Bijlsma’s core idea of music making, which can be perhaps better realized in the intimacy of small ensembles than in a large symphony orchestra. “When we talk, every word has a diminuendo, an accent perhaps. You wait a bit before you say something, maybe stretch out a syllable. That’s what makes talking interesting. And you can imitate it wonderfully on an instrument of course, when playing a Bach Suite for example. But with a baton for a hundred people? Conductors talk too much to me about ‘the long line.’”

The last time I was in Amsterdam, Bijlsma set his recently finished book about Bach’s Cello Suites No. 4-6 on the kitchen table. It was the third time he’d mentioned the Suites; the cellist’s holy text was a constant topic of reflection. A single original manuscript survives, from Anna Magdalena, Bach’s second wife. She didn’t play a string instrument, which is why it had been dealt with patronizingly and “improved upon” for two hundred years. Bijlsma was one of the first to take Anna Magdalena seriously. At some point, he played the suites in the way she’d notated them and stuck with it, the consequences of which were to be heard even in the very first Prelude.

The broken chords are no longer quick and legato, but accented, perceptible note for note. They work, he says, like a skyscraper with 5000 windows, 4997 of which are perfectly rectangular and new, but with three that are crooked and uneven. Those are the three that make it interesting—you might not hear them, but you’ve got to feel them. Anna Magdalena had valid reasons for writing her husband’s notes absolutely correctly—“when her husband wanted a text copied, a wife would do it as well as possible so that she’d go to heaven.”

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

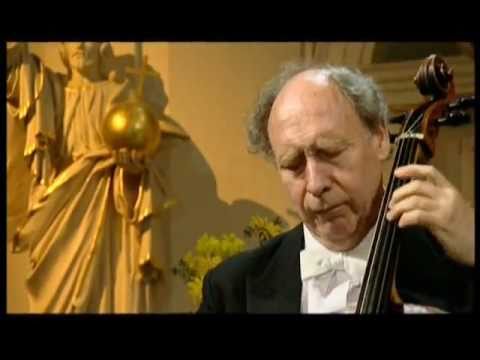

Bijlsma had lived with and within Bach. Until recently, without being able to play himself, he passed on what he knew about Bach and many others in workshops and masterclasses. His bow hand, bent at the joint and with its delicate fingers, would often pass through the air, now forever empty, holding a bow no more. His sparing use of vibrato made him stick out from the multitude of great cellists, and the first time we spoke I asked him why he played in such a way. “You never have to do anything. It has to come over you, it just has to happen,” he says. “The kid who falls over on the street and cries ‘Maaa-ma!’ doesn’t do so with vibrato, he just cries. There is no ‘should’ or ‘should not’ with vibrato. It either comes from the heart, or not at all.”

Of course, it’s not just the non vibrato. It’s what he does with his right hand, when on the left nothing happens, or there’s just a touch of expression, one of the hundreds of things one can do so that the sound breathes, carries and glows, fades and breaks, transparent and opaquely triumphant or timid and brittle. The tension shouldn’t break, the ear should be led along a dramaturgical thread. Not only a question of how, but of what—the historically accurate coordination of expression, and questions of style and of contemporary history are to be applied to the interpreter’s inner attitude.

“When you play something from a great like Bach, then you are of course, somewhere, always correct,” Bijlsma tells me. “There are colleagues who say that Bach is lyrical, so you have to sing it from beginning to end, and they’re right….Or somebody says that Bach was a religious person, and you always have to think about religion when playing his pieces. Correct. You can even say you have to play Bach like a sewing machine, and there are very well known people who play him like a sewing machine—indeed there are pieces that are a bit like a sewing machine. All of these people—and unfortunately they all teach—are correct in some way. Bach is all of that.”

Beethoven’s Cello Sonatas also hold a place in his heart. He recorded them with fortepianist Jos van Immerseel. “The recordings with Malcom Bilson gave me more pleasure,” he says when I bring it up. They do sound more musical, more impulsive, more free. Boccherini—whom musicologists tend to ignore, despite his impulsive, creative ignorance of sonata form—appeals to Bijlsma more than Haydn, about whom he has nevertheless learned as much as possible. “With the Concerto in D Major the score tells us everything,” he says. “As a cellist you get the impression that they weren’t written by Haydn alone. There were two people at work there, the solo cellist and student of Haydn Anton Kraft, and Haydn himself. I get the impression that the piece is a coproduction of two gentlemen, in friendship and respect.”

To better understand the Concerto and chamber music of Schumann, Bijlsma delved into the literature of the German Romantic and Vormärz periods, reading Jean Paul, Eichendorff, Grabbe and Büchner, and falling in love with Heine. One hot summer day, during the Boccherini Festival he founded, we sat in the cool dark of the apartment given to him in the Sierra de Gredos mountains, and he recited, by heart, verses from Novalis, as if phrasing on the cello. On his numerous travels, juggling life as a musician, there was always plenty of time to read, he says. “The afternoons in a hotel somewhere, before a concert in the evening, you have a little time. In the mornings the orchestra rehearses…and the concert is in the evening. Afterwards, the pianists walk with their suitcases through a dead city, where everybody is asleep in hotels. When you’re on the road with a string quartet or with our Archibudelli, you at least have time for a beer and a little fun together.”

Even when he’s talking about Mozart, who unfortunately only left a fragmentary Sinfonia Concertante for violin and cello for Bijlsma, he tells a story. But not one about the E-flat Major Divertimento that he loves so much because all three strings play completely equal roles; and not about the C Major Quintet, where the cello climbs the tonic, passing it and the melody to the first violin (“my wife”). Instead he talks about the darkly majestic Adagio for Glass Harmonica. Bijlsma once shared his accommodation with the soloist from that piece. “I got to the hotel at half past midnight, and sitting there was a counterpart of mine who played the glass harmonica, and who had done so his entire life,” he tells me. “He’d even treat his hands with sterile water for the instrument’s sake. And to fill me in on it, he played me the Mozart Adagio at half past midnight in the hotel room.” He adds, “I think the guests in the next room must have thought to themselves, ‘I’ve died and now I’m in the clouds.’ That’s how heavenly a glass harmonica sounds.”

Bijlsma has spent more than half his life in hotels. If it weren’t for his travels, he wouldn’t be living in two old brick houses at the edge of Amsterdam’s Vondelpark. “A funny world,” he says to me once, as we walk round the garden with a view of the houses, in one of which his first wife, the violinist Lucy van Dael, lives. “In school we learn how one can earn a lot of money, but not how one gets rid of it in an intelligent way.” He has learned, and seems through his travels to have remained faithful to himself.

“We musicians build a thin net for ourselves over the entire world,” he says. “We find a home everywhere. You play in New York, you visit your friends. Their kids have grown up. Everything’s nice. Sometimes you have a very special role to play. A friend in some city has issues with his marriage, he complains and he cries. He doesn’t do it with others, only with you, because he knows you won’t be back for another two years. And by then things are hopefully going better for him.”

I ask him if it saddens him not to play the cello. “No, for me it’s settled,” he answers. “I can’t even walk anymore. I can’t move my left hand anymore, I can’t even put my finger on it, you see? But the mental fingers are as fast as ever. Like with Beethoven, the beautiful thing is that you can actually do everything, you know exactly how. When I teach, I know everything, still. Not once do I have to think—everything’s there.

There are an innumerable amount of people who feel blessed by Anner Bijlsma. There seems to be no divide between music and life for him. Those who love him are saddened now to see how difficult these last few bars are for him. But he is not alone.

“The nicest thing is when you work together for decades, and still play the same pieces often,” he says. “You get older and gain more life experience, I don’t know what it is. Changing colleagues again and again—I don’t believe in it. It’s wonderful to grow old together.” ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.