On May 3, 2017, a young violist named Armando Cañizales Carrillo was killed in Caracas during clashes between demonstrators and the Bolivarian National Guard. The following day, the Venezuelan conductor and director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, Gustavo Dudamel, published a statement on Facebook calling for President Nicolás Maduro and the national government “to rectify and listen to the voice of the Venezuelan people.” He wrote: “The only weapons that can be given to people are the necessary tools to forge their future: books, brushes, musical instruments; in short, those that embody the highest values of the human spirit: good, truth and beauty.”

News reports in the U.S. and Europe acknowledged Dudamel’s earlier reluctance to speak out about the crisis in Venezuela, ongoing since 2014, yet responses to his statement were mostly positive. A predictable cheerleader was Mark Swed of the Los Angeles Times, whose adulation of Dudamel resembles the work of a publicist rather than a journalist. “Dudamel made one of the strongest statements of his career,” wrote Swed after the conductor dedicated a concert in Los Angeles to Cañizales Carrillo. Two days earlier, he had penned an article entitled “Gustavo Dudamel has tried to stay out of politics. Now, he’s demanding action in Venezuela.” Other newspapers followed suit in portraying the conductor as a man of action. “Venezuelan conductor Dudamel slams Maduro for repression,” trumpeted the Daily Mail. “Dudamel’s strong reaction against Maduro,” declared El País.

Responses to Dudamel’s statements by his fellow Venezuelans have been much more mixed. To understand why, we need to look at a longer sequence of events and consider why a Harvard economist and former government minister, Ricardo Hausmann, was moved to describe Dudamel as “a giant of a musician but a moral midget.”

A few weeks earlier, on April 4, another El Sistema musician, Frederick Chirino Pinto, was aggressively arrested by military police on a Caracas street, after his journey to a rehearsal had taken him past protests. Images of the scared young man clutching a French horn case circulated immediately online. Venezuelans called for Dudamel to respond, but he remained tight-lipped.

Many were outraged by his silence, but few were surprised. In a major interview in El País a few months earlier, Dudamel had stated his political position: “I simply don’t want to take any position.” A high-profile op-ed in the Los Angeles Times in 2015 was entitled “Gustavo Dudamel: Why I don’t talk Venezuelan politics.”

This was according to form. On February 12, 2014, when the last major outbreak of civil unrest began, Dudamel contributed to official celebrations for the Day of Youth with a gala concert. He did not react to the political upheaval going on around him, either during or afterwards.

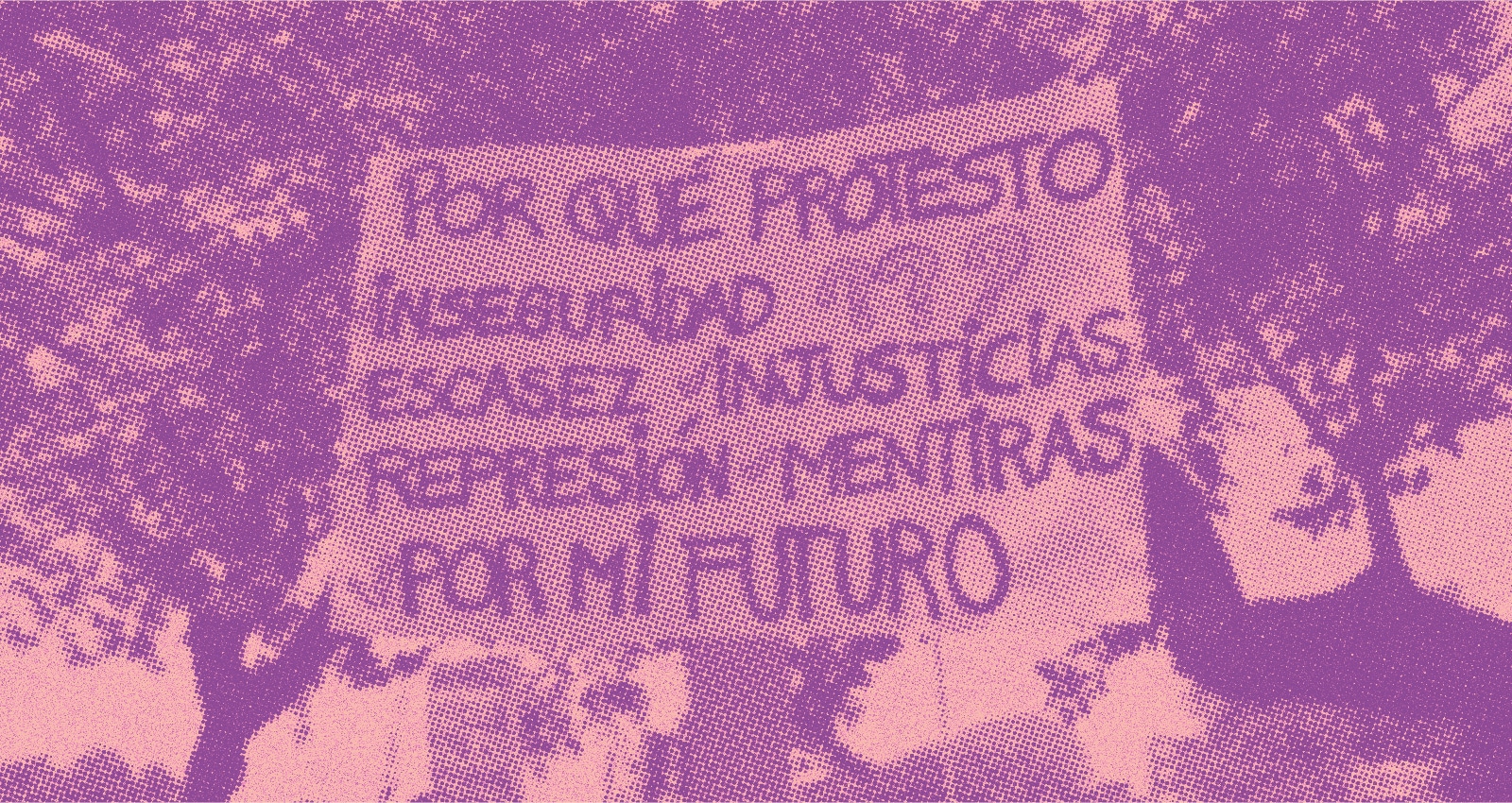

Since that moment, waves of criticism have followed every interview and silence, each one bigger than the last. So when Dudamel made his first public pronouncement on the crisis, a short video message, on April 25, 2017, many Venezuelans saw it as both a weak response (it was deliberately vague, directed at “political leaders” rather than the government) and a very tardy one (three weeks after the incident with the Sistema musician, three years after the start of the crisis). The onslaught on social media was extraordinary, even for those aware that the conductor’s reputation had been falling among his compatriots.

The death of Cañizales Carrillo was a more dramatic event than the arrest of Chirino Pinto, but it also seems likely that Dudamel and his advisors had learned their lesson from the previous week’s video. This time the conductor’s response was faster and firmer. It received more support than the video, but it also appeared that many were unwilling to forgive and forget years of silence on the basis of one Facebook post. Cañizales’s relatives rejected Dudamel’s message. His aunt wrote: “I will never forget the photos of Dudamel embracing Chávez and Maduro, I will never forget that they have boasted about El Sistema all over the world and my nephew even had to pay for his [viola] strings.” His uncle commented: “You are as responsible for the death of Armando as the same policeman who shot him. Don’t you dare mention his name, you’re a fake and a scoundrel.”

The idea that art and politics don’t mix, and that silence is therefore perfectly acceptable, is prevalent in Europe and North America, leading to more indulgence towards Dudamel. But this view is based on a profound misunderstanding of the conductor and the program behind him. El Sistema and politics have been mixed since the arrival of Hugo Chávez in power in 1999, and Dudamel’s career and program have been heartily supported by the Bolivarian Revolution. The idea that silence equates to political neutrality is therefore misguided, as many Venezuelans are well aware.

Those with longer memories recall the closure of the opposition-slanted Radio Caracas TV in 2007; as the channel went off the air, a Sistema choir and orchestra conducted by Dudamel performed the national anthem, inaugurating the government-run TVES channel on the same frequency. More recently, they have seen an El Sistema orchestra featuring prominently in the government’s anti-Obama campaign “Venezuela is hope”; foreign minister Delcy Rodríguez and the Simón Bolívar orchestra appearing together at the UN in early 2016, with the minister declaring that Dudamel was “our best ambassador to the world”; President Maduro personally backing plans for a Frank Gehry-designed Sala Dudamel concert hall in Barquisimeto, the conductor’s hometown; and Maduro announcing a $9-million budget for overseas tours by El Sistema’s top ensembles “to amaze and enamor the world,” at a time when he was forced to appeal to the UN for help with supplying medicines. Unsurprisingly, to many Venezuelans this looks less like neutrality or keeping art and politics apart than a cosy pact. As the Venezuelan conductor Manuel Hernández Silva responded in his own video message, in which he recalled Dudamel flying in on a private jet for Chávez’s funeral and crying on Maduro’s shoulder: “You’re a Chavista and you’ve always been one.”

Some are therefore skeptical of the idea that Dudamel has had a late change of heart. A tweet on May 8 by Diego Arria, a former Governor of Caracas and Venezuelan representative at the UN, claimed that the “Board of Directors [of the] Los Angeles Philharmonic pressured Dudamel to take a position as his relationship [with the] regime was affecting the orchestra’s reputation.” In an email, a press presentative of the orchestra said, “This statement was NOT made at the request of any LA Philharmonic representative.” Yet despite the fact that Arria’s tweet was unconfirmed, it was retweeted 2,462 times and counting, reflecting the depth of mistrust for Dudamel among Venezuelans.

Criticism of Dudamel has been led by another famous Venezuelan classical musician, the pianist Gabriela Montero. She has called the conductor a collaborator and his program “a corrupted instrument of power.” Alluding to his justification of his silence as a defense of El Sistema, she attacked his decision to prioritize musicians over the nation via a “utilitarian transaction of music funding for state propaganda,” and claimed that he had promoted “the illusion that the endlessly repeated, media-friendly, promoter-friendly, agent-friendly mantra of ‘social transformation through music’ would miraculously overpower the degenerative social effects” that the country was experiencing. (The illusory nature of El Sistema was recently demonstrated by a major study by the Inter-American Development Bank, which found little evidence of social effects, a high dropout rate, and—most damagingly for the Sistema myth—a low level of participation by the poor.)

Montero described Dudamel’s response to the death of Cañizales Carrillo as “playing his ‘Redemption Card’ ” to the world’s press. Indeed, now that he has spoken the international media has finally woken up, yet here too an illusion is being subtly fostered. Though most articles also mentioned, to a greater or lesser extent, the conductor’s earlier silence and the criticism he received for it, the headline and take-home message was: Venezuelan conductor bravely stands up to regime.

To many Venezuelans, though, things look rather different, because they have watched the story unfold slowly over years. They know Dudamel’s history of support from and for the government. They remember all the times that he has played along or kept quiet. This is simply the latest act in a long-running drama during which he has mostly acted as the loyal, compliant servant; the idea of Dudamel as a resistance hero doesn’t cut much ice. Tarde piaste pajarito is the phrase on many people’s lips: too little, too late.

For many of his compatriots, Dudamel is just one in a mass of prominent Venezuelans who have jumped ship or will do so after receiving copious benefits from the Bolivarian Revolution. Venezuelans watched El Sistema live the high life for years: as Gabriela Montero recently put it, the government provided Dudamel with “a limitless feast of hundreds of millions of dollars in the form of a government-owned propaganda machine, complete with the perks of private government jets, five-star endless summers touring around the world, and, of course, years of partying and fine dining with the Chavista hierarchy.” Now Venezuela is in crisis and money is tight; Dudamel’s critics say it’s no coincidence he has spoken in 2017 rather than during very similar events three years ago. Many comments invoke the image of a rat abandoning a sinking ship.

Where this is heading is very hard to know, just like the future of the Bolivarian Revolution. Some opposition supporters are welcoming Dudamel into their ranks; others are not about to let go of a suspicion and disdain that has been building for years. Even some musicians are asking why he kept quiet as the death toll mounted and yet spoke out immediately once a violist was killed: Are musicians more important than other members of society? It is possible that a few more carefully planned gestures—a big concert for peace and reconciliation, for example—will sway the doubters. But at present, he still seems a long way from convincing the Venezuelan public as a whole, and his position is now more precarious, because he is on the verge of creating a new foe. Within 24 hours of his latest pronouncement, government-aligned figures began publicly reminding him of all that he and his program had received. A three-month-old video of President Maduro assigning large sums of state money to El Sistema’s elite ensembles went immediately back into circulation. It is a hard sell for Dudamel to persuade the Venezuelan opposition that he is a genuine critic of a government from which he has gained so much, and Chavistas are unlikely to look kindly on the conductor if he jumps ship definitively after being treated as a favorite son of the revolution for many years. But overseas, audiences know less about Venezuelan politics and Dudamel’s controversial role and are therefore more forgiving. Between the pull of the global stage and the push of his disgruntled compatriots, overseas is probably where Dudamel’s future lies. ¶