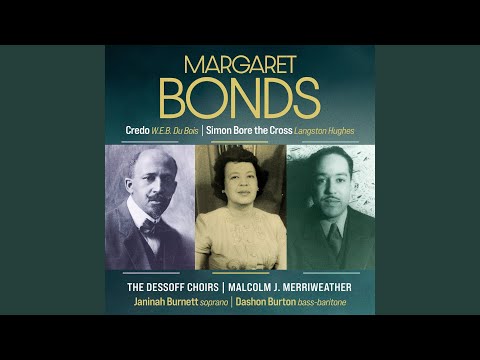

- The Dessoff Choirs, Malcolm J. Merriweather, Janinah Burnett, Dashon Burton: “Margaret Bonds: ‘Credo,’ ‘Simon Bore the Cross’” (Avie)

- Mivos Quartet: “Steve Reich: The String Quartets” (Deutsche Grammophon)

Early on in “The Factotum,” Will Liverman and K-Rico’s setting of “Il barbiere di Siviglia” in a Black barber shop, Liverman’s Figaro-ish character, Mike, sings about the legacy of carrying on the barber shop he inherited from his father. When Lyric Opera of Chicago shared a sneak peek of “The Factotum” in 2021, it included a clip of “Legacy,” and I asked Liverman about the relationship of that word to the larger themes of the opera. “It is exactly that,” he said. “Especially being people of color, it’s thinking about our legacies. And our family—that’s what it’s really about. Your family sets that foundation.…we’re building that foundation that was taken away from us from the start, and creating something finally where we can look back 400 years from now, and hopefully we have created a better world.”

I wish I could say I was reviewing “The Factotum” as part of this week’s column, but that recording hasn’t happened yet. (Though I’m not so hung up on journalistic objectivity that I won’t take this opportunity to publicly demand, in the relentless and unyielding manner of Veruca Salt, that Liverman and company make a recording. Now! Yesterday!)

I had “Legacy” in my head while researching the musical legacies of Margaret Bonds, after listening to the new recording of her choral works, “Credo” and “Simon Bore the Cross.” Both works speak to the musical legacy in which Bonds worked. There are subtle and not-so-subtle spiritual references, such as “He Never Said a Mumblin’ Word,” which runs as a leitmotif throughout “Simon Bore the Cross.” The Christmas carol “Hark the Herald Angels Sing”—based originally on a melody by Mendelssohn—comes up in “Credo.” The musical world which Bonds grew up around, featuring cameos from Florence Price and Will Marion Cook, is apparent. So are hints of Janáček and Tchaikovsky.

Even more apparent, however, is the literary legacy that shaped Bonds’s vocal music. “Credo” is based on W. E. B. Du Bois’s work of the same name, which built on Du Bois’s view of the world and the people who lived in it—both in America and Europe. Even more productive was Bonds’s relationship with her contemporary Langston Hughes. As a disillusioned Northwestern student struggling with segregation and racism, Bonds found a copy of Hughes’s “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” a poem that became her life raft at a critical time. Her setting of the poem became one of Bonds’s first published pieces.

Years after indirectly meeting Hughes, Bonds met the poet in real life. The two immediately clicked. Their Christmas cantata, “The Ballad of the Brown King,” was dedicated to Balthazar, centering the one demonstrably Black figure in the Nativity story. After a short version of “Ballad” premiered in 1954, Bonds revised the score for a full orchestration that was broadcast by CBS in December of 1960. The reach of this performance was galvanizing for its creators. “Trillions of people here saw the CBS broadcast,” Bonds wrote to Hughes the following year. “This is important to them. Your work and my work is vitally important to them—and our work is ourselves.”

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

A few years later, Bonds and Hughes were working on a follow-up of sorts, the “St. Matthew Passion” to the “Christmas Oratorio” of “Ballad.” But “Simon Bore the Cross” didn’t have the same lasting legacy as its predecessor—it wasn’t performed or published in Bonds’s lifetime. The score was considered lost until it was “discovered” in 2014. The five-minute prelude for orchestra and organ is a chamber drama; you almost need to hit pause before going into the first vocal excerpt, which sets off the story of Simon of Cyrene, another Black man central to the life of Christ, this time the man who carried his cross to the crucifixion site. The shades of Bach give way to a sweeping evocation of Americana, clearing prairies, plains, and deserts that suits the story like a custom-made glove. Here is a familiar story, reframed from a less-familiar point of view. Now, we hear it within the circles that Bonds and Hughes lived and worked.

As Allegra Martin noted in her 2019 dissertation on “Simon Bore the Cross,” the wordless prelude would still ring familiar to any listener who knew the work—and their attention would be explicitly drawn to the notes used to set “Christ.” Martin also points out that the ubiquity of Simon of Cyrene in 20th-century Black culture would have been a connecting point for “Simon Bore the Cross.” She describes Hughes’s libretto as a “construction of counter-memory,” aimed at “instill[ing] in Black listeners a sense of dignity and pride.” It’s an act of reframing the legacy, building on a foundation that was set millennia ago. In the work’s first recording, the Dessoff Choirs under Malcolm J. Merriweather give “Simon” an evangelical reading, with a gorgeously wrought vocal patina that sounds at once hushed and exultant. It’s contemporary experience grounded in historical precedent.

That same balance is the hinge for Steve Reich’s “Different Trains,” a work that’s the direct result of its composer’s childhood. When Reich’s parents split up, his mother moved to Los Angeles while his father remained in New York. That left a young Reich to cross the country by train between 1939 and 1942. “While the trips were exciting and romantic at the time,” Reich would later write, “I now look back and think that, if I had been in Europe during this period, as a Jew I would have had to ride very different trains.” His resulting (and landmark) 1988 work is a contemporary quartet grounded in both personal and world history.

As I type these words, I’m sitting in a hotel room in Dnipro, Ukraine—approximately four-and-a-half hours from the Russian border. It’s hard not to connect the two experiences; hard not to have the experience of sitting in a city acutely aware of war in 2023 inform the experience of listening to a string quartet borne out of that same awareness, albeit an awareness in retrospect. The air raid sirens Reich samples in his second movement, “Europe During the War,” are so similar to the sirens here that I’ve found myself once again hitting pause, checking my phone, opening the window, before hitting play again.

In this context, the Mivos Quartet’s new recording of “Different Trains,” presented as part of a larger collection of Reich’s works for string quartet, couldn’t be more presciently timed. There’s the heartbeat of source material that Reich uses: recordings of his former governess, Virginia, talking about the train trips they took together during his youth; recordings with a retired Pullman porter, Lawrence Davis; reminiscences of Holocaust survivors that were about Reich’s age; and both American and European train sounds of the ’30s and ’40s. It’s a painstaking work of cultural anthropology, lurking under a layer of trailblazing minimalist barnstorming.

There is also always the constant of these field recordings in any performance of “Different Trains,” leaving a larger-than-normal onus on the performing quartet to deliver something unique and vital to the conversation. There’s a renewed sense of fervor and energy in the musicians of Mivos. Without overtaking the recordings at the heart of Reich’s work, they undergird them in such a way that it feels fresh, a perspective that’s been slightly shifted. In 1988, Reich couldn’t have possibly guessed that the history of his childhood would repeat itself. Mivos reminds us of how close to the bone the past can hit. Hearing Holocaust survivor Paul categorically declare that “The war was over” in the work’s third movement, followed closely by fellow survivor Rachella asking—with a voice both challenging and fractured—“Are you sure?” is an occupational hazard. You risk being suffocated by context and legacy. ¶