When Tolstoy began working on what would become War and Peace, his 1869 opus that moves fluidly between historical novel and philosophical treatise, he initially had a completely different story in mind. Rather than craft a constellation of parallel and intersecting histories between 1805 and 1820 (with a particular focus on Napoleon’s 1812 invasion of Russia), Tolstoy had wanted to write something rooted in the present: He would begin in 1856, and tell the story of an elderly member of the Decembrists returning to Moscow after three decades in Siberian exile.

Tolstoy then realized that, in order to anchor the reader in the significance of such a man going home again, he would need to go back to the Decembrist revolt of 1825 (wherein a faction of loyalists to Konstantine, the heir apparent to the recently-deceased Tsar Alexander I, attempted to wrest power from his newly-coronated younger brother, Nicholas I). In order to make sense of this attempted coup, however, Tolstoy realized he would need to go back even further—to Russia’s War of 1812 and the reign of Alexander I. In one final round of this game of infinite regression, Tolstoy ultimately scrapped the Decembrist plot and focused on an entirely new cast of characters. He began in 1805, at the dawn of the Napoleonic age in Russia. The center of the book both literally and figuratively became the war; the September 1812 Battle of Borodino a political and moral turning point.

The latest from VAN, delivered straight to your inbox

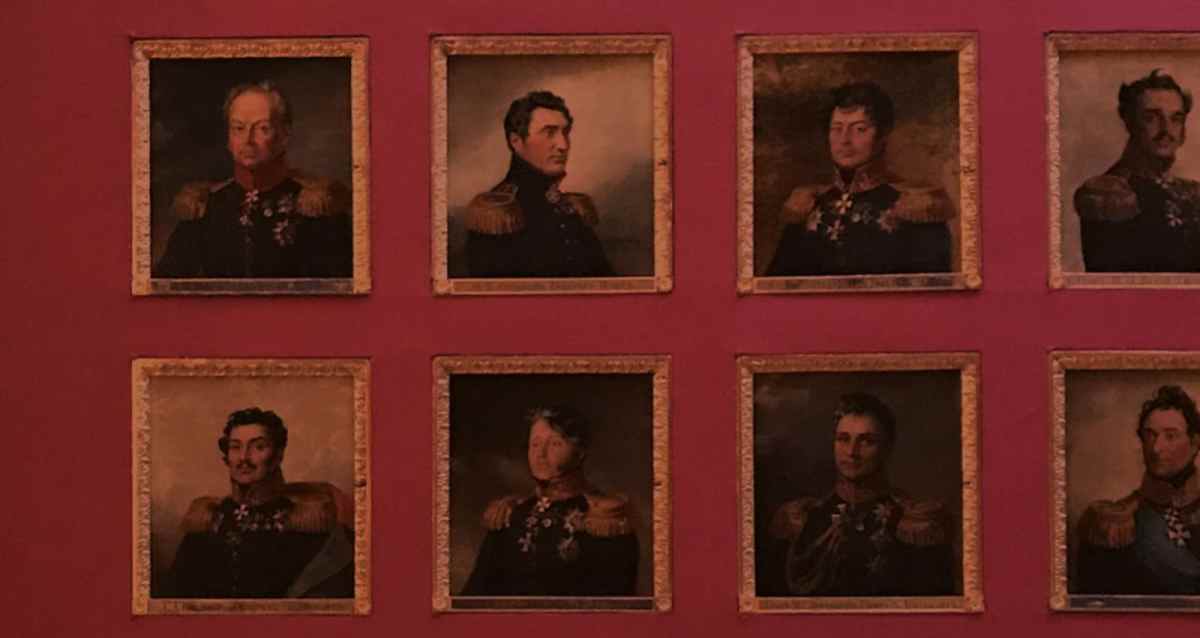

Until World War I, Borodino was the single bloodiest day in the history of warfare, which is in part why Tolstoy gives it over 100 pages, enough to allow for the interplay of history and histrionics. He also considers the individual self versus the collective unconscious: Every single person involved in the battle, from Napoleon and Alexander I, down the ranks from the generals to the officers, enlisted men, and attending serfs, could have triggered a butterfly effect that might have dramatically altered the course of history. If, that, is all other coinciding causes also fell into place.

“The more we try to explain sensibly these phenomena of history, the more senseless and incomprehensible they become for us,” he concludes. We are all caught up in a web of history that simultaneously reaches into the darkest recesses of past memory and the unknowable expectations of the future. This represents a philosophical throughline that can be traced back to some of Tolstoy’s schoolboy compositions: “That is why the life of a man consists in nothing but the future and the past, and it is for the same reason that the happiness we want to possess is nothing but a chimera, just as the present is.”

Tchaikovsky, who was a contemporary of Tolstoy’s and revered the author, echoed this sentiment in one of his letters: “To regret the past, to hope in the future, and never to be satisfied with the present—this is my life.” Also like Tolstoy and War and Peace, one of the works that Tchaikovsky is now best remembered for is his work that dealt in the Russian triumph in the War of 1812.

At first glance, this is where the similarities end. Where War and Peace is vast and voluminous, Tchaikovsky’s “Solemn Overture for the Year 1812” is a brisk 15 minutes of mostly easy listening. Unlike Tolstoy, Tchaikovsky makes no comment on history as a tapestry of cause and causality. And while both works have lasted, War and Peace is seen as a sober accomplishment while “1812” could be considered its more fun-loving, crowd-pleasing cousin. For many, it’s a work best siloed alongside equally unserious pieces like Beethoven’s blandly propagandistic “Wellington’s Victory.” A 2008 New York Times review commended the New York Philharmonic for making the bold choice to treat the work “as a respectable score.”

Tchaikovsky himself would have had no argument: “The overture will be very noisy,” he wrote to his patron and confidante Nadezhda von Meck after finishing the work in 1880. “I wrote it without much warmth or enthusiasm, therefore it has no great artistic value.” The nationalism and pomp that the piece required for the occasion of its commission (the All-Russian Arts and Industrial Exhibition of 1881) was a poor fit for the introverted, cosmopolitan composer.

And yet, there is something compulsively listenable about “1812.” A depth of rhetoric and gesture justifies, if not the piece’s commercial ubiquity, then at the very least multiple listens. It’s precisely Tchaikovsky’s nationalistic apathy that lends the work much of its intricacy. Before moving into the clash of national anthems, Tchaikovsky begins by quoting the well-known Russian Orthodox hymn, “O Lord, Save Thy People.” Much like Tolstoy, he centers the individual in the web of history, locating the innermost sanctum of the personal within the political.

This supplication becomes an opening salvo for Tchaikovsky to rove relentlessly across fields of association—presaging his later apotheosis of sonic collage, “Pique Dame.” An oboe, like the voice in the wilderness, cuts through the liturgical gloaming. We’re in the shit of Borodino, fields soaked in blood, chaos under the canopy of cannon fire, before reaching the familiar talking point of “1812,” the clash of French and Russian national anthems (“La Marseillaise” and “God Save the Tsar,” respectively). Not that either of these anthems were in use in 1812: ”God Save the Tsar” had only been composed in 1834, and Napoleon had banned “La Marseillaise” following the French Revolution (the same revolution that likely drove Tchaikovsky’s own French ancestors to Russia).

These conscious anachronisms on Tchaikovsky’s part are kinks in the web of history, a suggestion of its senselessness and incomprehensibility. Is history moving forwards or backwards? The “Marseillaise” isn’t simply drowned out by “God Save the Tsar.” It’s continually ebbed under a battalion of influences and impulses. This includes a duet Tchaikovsky recycled from his early, scrapped opera “The Voyevoda,” the Russian folk song “At the Gate,” and a reiteration of “O Lord, Save Thy People” that is buttressed by quotes from “God Save the Tsar.” In context, the cannons are perhaps the least interesting part.

If only subconsciously, Tchaikovsky was crafting a personal narrative as much as he was phoning in a historical one. Modest Tchaikovsky would write that his brother’s life “moved in spiral convolutions,” fluctuating between lightness and shade, past memory and future expectation. The only thing constant for him seemed to be his dissatisfaction. (After one performance of “1812” in St. Petersburg, he jotted down in his diary: “My concert. Complete success. Great enjoyment—but still, why this drop of gall in my honey-pot?”)

The premiere of “1812” would be shaped by one of history’s hairpin curves: Shortly before the All-Russian Arts and Industrial Exhibition, Alexander II was assassinated. Upon learning the news while in Rome, Tchaikovsky wrote to his brother in a rare moment of homesickness: “At such moments it is very miserable to be abroad. I long to be in Russia… in short, to be living in touch with one’s own people.”

The Exhibition was postponed to 1882, and “1812” enjoyed a successful premiere. While Alexander III became tsar immediately following his father’s murder, his official coronation was postponed by more than two years—to May of 1883—due to security concerns. Rumors persisted that he would never have an official coronation, or that he had been coronated in secret. Nevertheless, Alexander III had his pomp and spectacle, and used the occasion to call for unity and reconciliation between a politically- and socially-divided Russia.

As part of the ceremonies, “1812” was brought out once again as a show of cultural power. Historian Richard Wortman suggests it was also a bit of image control on Alexander III’s part: “The monarchy appropriated the victory over Napoleon and presented it as a symbol of the recent triumph over the revolutionaries.” Who could then blame Tchaikovsky (who skipped out on the coronation by sequestering in Paris) for continuing to denigrate his work?

In 1876, Tchaikovsky had the chance to meet his idol when Tolstoy, in the middle of publishing Anna Karenina, came to Moscow. There was a mutual admiration between the two artists, although Tolstoy had urged Tchaikovsky to give up on opera as an untenable and unrealistic art form. Tchaikovsky seemed sympathetic to Tolstoy’s stance, but, as he would later wrote to Nadezhda von Meck, the lack of historical accuracy was superfluous in the right context: “forgetful of the lack of absolute truth, I marvel at the depth of conditional truth, and my intellect is silenced.”

Tchaikovsky’s hatred for “1812” and its political appropriation don’t necessarily take away from the work’s value. If anything, it enhances it, matryoshka-ing the work in successive layers of meaning. Remove all of the outer dolls of the overture, and you’re left at the center with its composer, a man of contradictions, of virtues and faults, of hopes and regrets. “1812” doesn’t get to the absolute truth of personal or political history, but with both it’s able to reach a depth of conditional truth.

It’s enough to silence one’s intellect. ¶

Subscribers keep VAN running!

VAN is proud to be an independent classical music magazine thanks to our subscribers. For just over 10 cents a day, you can enjoy unlimited access to over 875 articles in our archives—and get new ones delivered straight to your inbox each week.

Not ready to commit to a full year?

You can test-drive VAN for one month for the price of a coffee.

Comments are closed.